The surviving photographs of my great-grandfather Isbrand Janzen (b. 1863) consistently give profile to his cane.

Our earliest photograph of Isbrand is about 1902, age 38 in

Spat, Crimea. His cane or crutch is on prominent display and already

part of his identity. He married late—age 32 in 1893; maybe because of his leg?

His wife was the widow Elisabeth Plönnert Böse, and she brought three children

into the marriage.

In their fifth year of marriage the couple experienced a double grief: their two children died within nine days each other, ages 1½ and 3, January 1898 (note 1).

Both Isbrand and Elisabeth were born in the Molotschna

Colony in the village of Petershagen; Elisabeth’s parents were more recent

immigrants (note 2). Isbrand’s grandfather was one of the pioneer settlers of

the village.

How and when Isbrand came to Crimea is unclear. In 1860

after the Crimean War, the Molotschna Colony purchased 40,000 desiatini of land

in Crimea for a daughter colony. By the start of World War I, approximately

3,500 Mennonites were living in Crimea, and 4,817 Mennonites (892 families) in

1926 across 70 villages (note 4).

Isbrand was not an estate owner, but the first family

portrait indicates that they were materially comfortable. The second family

photo was taken ca. 1907. Again, the cane is profiled as part of his identity.

The youngest in the photograph would die skating on a pond with two Teichrob

boys in 1914.

During the Russian Revolution the Crimean Peninsula was the last hold-out of the White Army, and so the population was not raided by the Makhno anarchists as in the mother colonies. But the Revolution left destruction everywhere.

Starting 1921 Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) allowed for

some small-scale private farms and cooperative organizations, and Mennonites

were quick to try and rebuild within the limits imposed; the Crimean Mennonite

Agricultural Society was soon organized (note 5). The famine of 1922 took on

horrific proportions (note 6).

American Mennonite Relief came largely through the Crimean

port city of Sevastopol, and Mennonites in Spat—one of the largest Mennonite

villages in Crimea, with high school, mills, churches. etc.—benefitted.

When the American Fordson tractors arrived, there was a lack

of specialists to operate and maintain them, and the Agricultural Society made

an effort to train "tractorists” (note 7). The small freedoms of the early

1920s did not last long and, like the sister society in Molotschna, the Society

was soon forced to close (for a sample “poison” letter to the Bolshevik German

newspaper for Crimea in 1926, cf. note 8).

For Crimean Mennonites, their greatest fear was for their children’s future, and this grew from year to year. In 1928, Saat (Communist “Seed”), the organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League of Ukraine published the following article: “A Declaration of Crimean Mennonite Youth to the Soviet Government: 'Youth Expose the Hoax of the Preachers. The Mennonite youth joins the ranks of the active defenders of the S.S.S.R.'" The article claimed that forty-two Crimean Mennonites signed their readiness to enter military service with arms. The claims of the paper were dubious at best, but the probability that their youth would rapidly distance themselves from church was real and an ever-present anxiety. Isbrand’s children were still part of that demographic (note 9).

Isbrand and family were among those who would make one last

desperate attempt to flee the Soviet Union via Moscow. 4,000 Mennonites had

already descended on the capital by October 29, 1929. A Secret Police (GPU)

report based on a sample survey of five village councils in the Simferopol

District (Crimea) dated November 5, 1929, listed 50 families that were ready to

leave and another 314 people who were in the process of selling their property

(note 10). By mid-November that number had mushroomed to over 12,000 (note 11).

Isbrand and his wife and four adult children and few

grandchildren were among those who were successfully transported to Germany,

with hopes to be in Canada soon (note 12). Perhaps because of his leg, he and

wife Elisabeth and their two unmarried adult daughters were not given clearance

to enter Canada.

Their son Isbrand I. Janzen (Jr.) and his step-son Martin

Boese with families left for Canada from Hamburg on April 1, 1930, but not

before one of the grandchildren (Willi, age 10 months) died in an epidemic

outbreak in the refugee housing (note 13).

A 1930 MCC photograph from Germany shows a group of men

planning--perhaps for the new settlement in Paraguay—and Isbrand is at the

table, age 66 (note 14). The end of the crutch is barely visible under the

table. On July 11, 1930, one day before departure, the group crafted a letter

to MCC, indicating that their flight from their homes was for the sake of the

faith of their children. They knew that they were among the fortunate ones to

be saved “and to have found a temporary warm welcome in our old motherland

[Germany]. As is well known, our destination was Canada ... but since the

situation is such that only a limited number of our co-sufferers could enter

Canada, we are deeply moved that the Mennonites of the USA take such a great

interest in our fate and extend their helping hand to us with advice and deeds.”

(Note 15)

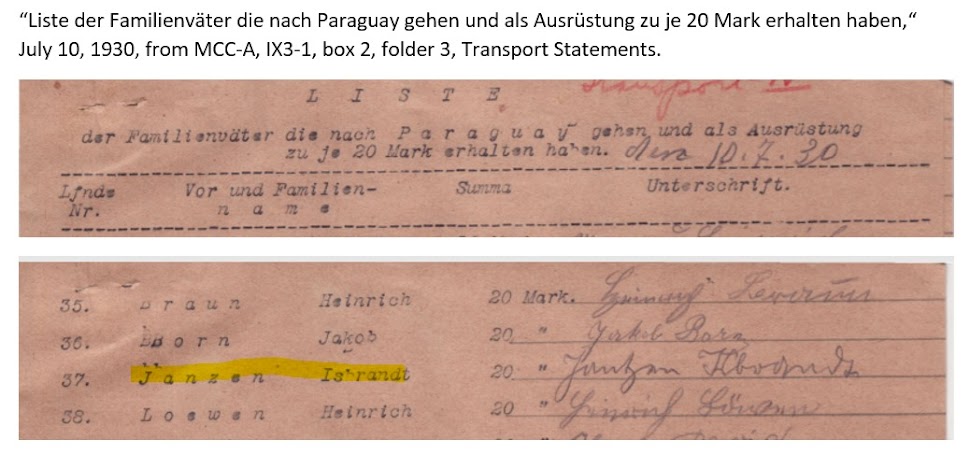

With the steamship "Villagarcia," MCC’s fourth Paraguay transport departed on July 12, 1930 from Hamburg. These 64 families of 353 individuals arrived in Buenos Aires on August 9, prepared to settle into three new villages of 25 families each (villages nos. 9, 10 and 11). Of the 1,572 refugees that were transported and settled in Paraguay by MCC in 1930, 585 were from Ukraine or Crimea (note 16).

Isbrand’s family settled in village no. 10, Rosenort, Fernheim Colony, Gran Chaco. Very soon a significant epidemic broke out among the new settlers—all living in the most primitive conditions and without a medical doctor.

Isbrand’s wife Elisabeth was one of the first to die. His

daughter Helena would soon marry Jakob Fast also in village no. 10, whose wife

and child also died from the Fernheim epidemic—all before Christmas 1930 (note

17). Their first child was my father, Peter Fast—Isbrand’s first grandchild in

Paraguay.

This family would be among those who were disappointed with the conditions and prospects in Fernheim and—without options to immigrate to Canada or return to Germany—they sought to establish a new colony in east Paraguay, Friesland in 1937 (note 18). From 1933 until the end of the war, many in Fernheim and the majority of those in Friesland were taken up with excitement for National Socialism (note 19). The community was still very poor when Isbrand died in Friesland, 1944. He had spent the last years of his life in the household of daughter Elisabeth Janzen Peters.

His final portrait has an almost artistic quality. But the crutch is missing as he sits on his bed. His handicap was part of his identity. I think of the biblical figure of Jacob—we are told he wrestled with God and angels and was left with a limp … and a blessing for his descendants.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: On Mennonite child mortality rates in Russia, cf. my

previous post: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/the-cycle-of-time-and-maternal-and.html.

Note 2: For background on the Plönnert /Plennert Mennonite

name, cf. see my previous post (forthcoming).

Note 3: On the Mennonite experience during the Crimean War,

cf. my previous post: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/mennonites-and-crimean-war-1853-56.html.

Note 4: In Adolf Ehrt, Das Mennonitentum in Rußland von

seiner Einwanderung bis zur Gegenwart (Berlin-Leipzig: Belz, 1932), 78, https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/?file=Pis/Ehrt.pdf.

Note 5: On the Mennonite response to Lenin’s New Economic Plan,

cf. my previous post: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/1921-formation-of-union-of-citizens-of.html.

Note 6: On the famine of 1921 and 1922 in Ukraine and the

impact on the Mennonite communities, cf. my previous posts (forthcoming).

Note 7: On the Crimean Mennonite Agricultural Society, cf.

Martin Durksen, Die Krim war unsere Heimat (Winnipeg, MB: Christian Press,

1977), 177f. https://archive.org/details/DieKrimWarUnsereHeimOCROpt/page/n177/mode/2up.

Cf. also my previous posts (forthcoming)

Note 8: "Aus der Krim. Spat. 55,000 Rubel Defizit im

mennonitischen Verein," Das Neue Dorf, 63 (13) (1926), 5, https://martin-opitz-bibliothek.de/de/elektronischer-lesesaal?action=book&bookId=via000515#lg=1&slide=0.

Note 9: Cf. "Deklaration mennonitischer Jugendlicher

der Krim an die Sowjet-Regierung," Saat no. 7/8 (Novemer 7, 1928), cited

by Ehrt, Das Mennonitentum in Rußland, 146. For a selection of Saat issues from

1928, cf. https://kat.martin-opitz-bibliothek.de/vufind/Search/Results?lookfor=saat&type=AllFields&daterange%5B%5D=publishDate&publishDatefrom=1921&publishDateto=1931.

Note 10: Cited in Detlef Brandes and Andrej I. Savin, eds., Die

Sibiriendeutschen im Sowjetstaat 1919–1938 (Essen: Klartext, 2001), 296.

Note 11: On the flight to Moscow, cf. my previous posts

(forthcoming; see also Table of Contents).

Note 12: On the refugee experience in Germany, cf. my

previous posts (forthcoming).

Note 13: On Canada’s restrictive measures, and the

difficulties for entering Canada in 1930, cf. my previous posts (forthcoming).

Note 14: On MCC’s flurry of activity to resettle this group,

cf. my previous post (forthcoming), as well as the passenger lists compiled by

Ron Isaak: “Mennonite Passenger lists for Refugee Transport to Paraguay in 1930,”

http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/latin/paraguay1930.htm; AND https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/latin/paraguaycombined.htm.

Note 15: "An das M.C.C. USA, “Dankschreiben der vierten

nach Paraguay gehenden Gruppe,“ MCC-Akron, IX3-1, fox 1, file 6, document 0004.

Note 16: On the transport to Paraguay, cf. my previous post

(forthcoming); also: Harold S. Bender to Max Kratz, letter, July 14, 1930,

MCC-Akron archives, IX3-1, Box 3, file 80003.

Note 17: On the Fernheim epidemic, see my previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/03/what-does-it-cost-to-settle-refugee.html.

Note 18: On the letters sent by grandmother, Isbrand’s daughter

Helene, to siblings in Canada, see my previous post (forthcoming).

Note 19: On the Nazi influence in the Mennonite colonies of Fernheim and Friesland beginning 1933, see my previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2022/09/eradicating-communist-spirit-in-young.html.

Comments

Post a Comment