Katharina Esau offered me a home away from home when I was a student in Germany in the 1980s. The Soviet Union released her and her family in 1972. Käthe Heinrichs—her maiden name (b. Aug. 18, 1928)—and my Uncle Walter Bräul were classmates in Gnadenfeld during Nazi occupation of Ukraine, and experienced the Gnadenfeld group “trek” as 15-year-olds together. Before she passed, she wrote her story (note 1)—and I had opportunity to interview my uncle.

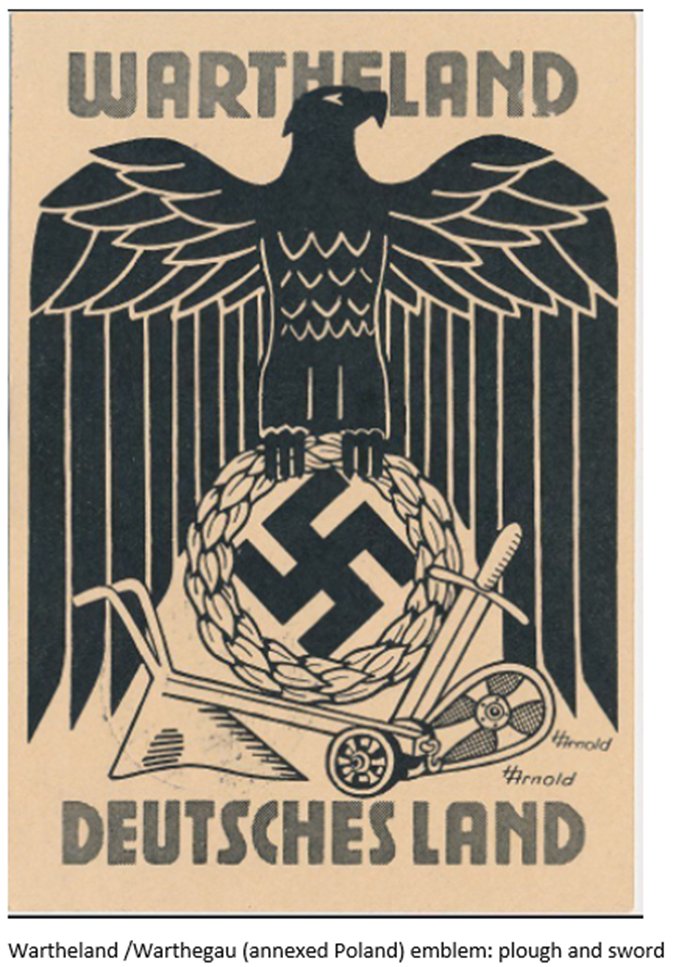

Käthe and Walter both arrived in Warthegau—German annexed Poland—in March 1944 (note 2), and the Reich had a plan for their lives.

In February 1944, the Governor of Warthegau ordered the

Hitler Youth (HJ) organization to “care for Black Sea German youth” (note 3).

Youth were examined for the Hitler Youth, but also for suitability for elite

tracks like the one-year Landjahr (farm year and service) program. The highly

politicized training of the Landjahr was available for young people in Hitler

Youth and its counterpart the League of German Girls, after the completion of

school at age 14. Applicants had to be fit—physically, genetically (Aryan), and

mentally (notes 4); both Walter and Käthe Heinrichs were steered toward the

“elite” tracks.

For Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) boys, Hitler-Jugend was obligatory, and a prerequisite for any future roles in civil (Volks-) society. For Walter, HJ began with the compulsory labour service unit (Arbeitsdienst) and pre-military camp (Wehrertüchtigungslager). The latter included rifle training and trench digging (note 5). Already in Ukraine, the HJ organization enticed Mennonite boys with opportunities for sport, collegiality, shooting exercises, theoretical and practical training under the leadership of a reserve officer, at no cost with a small stipend, decent lodging and food more “plentiful than mother’s cooking pot” (note 6). The HJ camp at Posen/Warthegau stressed the importance of camaraderie and taught boys, e.g., how to fight in pairs in the trenches. Practice included entering an “enemy” trench in the darkness and throwing out whomever they encountered. Because Walter did this well and without fear, he was encouraged to sign up for the officers training track when he turned 16 in April.

Käthe Heinrichs arrived in Warthegau with typhus, but after a recovery she entered preparatory training for the Landjahr in May and then entered the Landjahr and Landdienst schooling program in August 9, 1944, together with Käthe Rempel (note 7). Their Landjahr school was in Scharfenort, Kreis Samter. Here they learnt “to cook, to do laundry, to iron clothing and bedding, to clean, and to do garden work." They apprenticed in the mornings at different farmsteads or estates, and then would change groups every two weeks. Fitness training was part of the program, and here she learnt to swim and dive. “As long as it was warm in the fall, we had swimming once a week in the afternoons. We also learnt to dive into the water from a diving board at a height of three meters … for this I had to go to Poznan to use the indoor pool, because it was already too cold outside” (note 7).

The regime was grooming these 15-year-olds to be elite farming families and communities for Germany’s eastern borders at war’s end. The vision called for a genetically healthy German peasant stock in fortified agricultural villages along Warthegau’s border. Accordingly, Warthegau’s emblem was the plough and sword, Mennonite resettlement in Warthegau, and perhaps later again back to Ukraine, was to help fulfill this plan. “This future, too, can only be a soldierly future. … Only a soldierly generation proud of its military will know how to preserve the heritage of the victory. When these young people will one day live as soldier-farmers (Wehrbauern) in the German East on their own land, we will no longer have to worry about our German future” (note 8). The Wehrbauer ideal—a plough in one hand and the sharpened sword in the other (note 9)—was introduced in HJ and in the Landjahr programs in Warthegau.

Already in 1939, a memorandum by the Nazi Party (NSDAP)

Office of Racial Policy indicated their expectation that large numbers of

ethnic Germans from Canada and “primarily Mennonites” from Paraguay, Uruguay,

Argentina and Mexico would also desire to “return home” and could be settled in

the newly annexed eastern German territory. Ethnic German resettlers would be

given generous space as “soldier-farmers” (Wehrbauern) to freely allow their

"natural mastery (Herrentum) to enfold," and Poles would be forced

off their land to serve exclusively as labourers and servants of the ruling

German racial class. The Party memo was optimistic that a next generation of

Mennonites would gradually grow out of their narrow “confessionally-conditioned

way of life and no longer be distinguishable from the larger German population”

(note 10).

Hitler’s evolving vision was for an agricultural renaissance

of armed German soldier-farmers on the eastern front prepared to defend the

land at all times, to teach the next generation, and to keep the racial order.

“The Wartheland is a living rampart in the German East, but also a farming

province and province of front-line soldiers …Germany's largest agricultural

province is only secure if, in addition to the plow, the sword also remains

sharpened” (note 11).

Here is a curious interim report by the Landjahr national

director upon her visit to a camp with girls who started April 1, 1944:

“The Black Sea German girls [Mennonites would be included in

this group]seem willing to work and eager to learn. Nevertheless, the

educational work turns out to be extremely difficult, as they have a completely

different attitude to work than our German girls.

The camp leader reported that it was very difficult to train

the girls to be companionable and eager to do their work. In Russia they are

used to being assigned a certain amount of work that they either do quickly or

very slowly. If they work faster, they can use the spare time for themselves.

Furthermore, they only do the work that has been assigned to them and explained

in detail. Any additional work that may arise ... is not done because it is not

ordered. This kind of attitude toward the performance of work, which runs

counter to our German attitude ..., is very difficult for the Black Sea German

girls to get used to. In addition, there is a certain distrust that the girls

have in principle towards the orders of Germans. They are only slowly being

convinced that they are treated on an equal footing with the German girls.

Another difficulty arises from the fact that the girls are

used to different foods than we eat here in Germany. Vegetables or salads are

foreign to them, and they are only used to eating a limited variety of fruit.

Linguistically, they try to speak perfect German. They have

a very poor command of proper spelling, and no grammatical knowledge

whatsoever. Elementary arithmetic skills are also poor. However with firm,

purposeful and understanding guidance, the Black Sea German girls will adapt

well to our way of life. The Black Sea Germans will need a very long time to

acclimatize, however." (Note 12)

As Walter and Käthe were starting their training, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler gave a speech to his officers (July 1944) noting that Germany’s goal must be to push “the German national border at least 500 km eastwards from the border of 1939. It is necessary to settle this area with Germanic sons and Germanic families, so that a planted garden of Germanic blood is created, so that we continue to be an agricultural people” (note 13).

Already during German occupation of Ukraine, the Volksdeutsche were reminded time and again that this was a righteous battle for German freedom, German blood, and German living space—so that Germans will never again be brought to their knees in hunger like after the Great War (note 14).

The Nazi German racially-based ideals were failures on all

levels. In different ways Hitler’s bizarre plans cost the lives not only of

millions of Jews, Poles and other peoples, but also of three of Walter’s

brothers and a sister (all siblings to my mother). Young Käthe Heinrichs fell

into the hands of advancing Soviet troops, and her misery took on whole new

dimensions for the next two decades.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Katharina Heinrichs Esau (#1407884, born August 18,

1928), “So bleibt es nicht. Erinnerungen aus meiner Kindheit [bis 1945],” 2002.

In author’s possession. Katharina Heinrichs (Esau) was born August 18, 1928.

Note 2: “Von der Molotschna bis zur Warthe,” Ostdeutscher

Beobachter 6, no. 71 (March 12, 1944), 5, https://www.wbc.poznan.pl/dlibra/publication/125852/edition/134988/content.

Note 3: February 25, 1944, Governor for Reichgau Wartheland, Unterbringung der Schwarzmeerdeutsche. Der Reichsstatthalter im Reichsgau

Wartheland Posen (GK 62) / Namiestnik Rzeszy w Okręgu Kraju Warty. From NAC, 53/299/0,

series 2.2, file 1978, 140, no. 145, https://www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/de/jednostka/-/jednostka/1049367.

Note 4: August 4, 1944, State Health Office Eichenbrück, Transport of Germans from the Black Sea to the Wartheland (Transport Niemców

znad Morza Czarnego na teren Kraju Warty), 318, no. 327. From Narodowe Archiwum

Cyfrowe (National Digital Archives Poland), 53/299/0, series 2.2, file 1979, https://szukajwarchiwach.pl/53/299/0/2.2/1979/.

Note 5: “Randbemerkungen,” Deutsche Ukraine-Zeitung (DUZ) 1,

no. 100 (May 19, 1942), 2, https://libraria.ua/en/all-titles/group/875/.

Note 6: "Besuch in einem Wehr-Ertüchtigungslager

unserer HJ," Litzmannstädter Zeitung 27, no. 338 (December 22, 1944), 3, https://bc.wimbp.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication/31689/edition/30230/content.

The article provides a very good description of the schooling. See also

articles in papers available in the Molotschna during German occupation:

“Schule für künftige Soldaten: Warum Wehrertüchtigungslager,” DUZ 1, no. 255

(November 15, 1942), 8, https://libraria.ua/en/all-titles/group/875/; cf.

also“300.000 lernen Schilaufen,” Ukraine Post, no. 19 (May 15, 1943), 5f., https://libraria.ua/en/all-titles/group/878/.

Note 7: Landjahr pics from Wir erleben das Landjahr. Ein

Bildbericht von dem Landjahrleben, 4th ed., edited by Walter Höfft

(Braunschweig: Appelhans, 1941), 85.

Note 8: “Berufssoldaten von morgen,” DUZ 2, no. 38 (February

14, 1943), 8, https://libraria.ua/en/numbers/875/32166/.

Note 9: E.g., Litzmannstädter Zeitung (March 18, 1944), 6, http://bc.wimbp.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication?id=31097&tab=3.

Note 10: E. Wetzel and G. Hecht, NSDAP Office of Racial

Policy, November 25, 1939, “Denkschrift: Die Frage der Behandlung der

Bevölkerung der ehemaligen polnischen Gebiete nach rassenpolitischen

Gesichtspunkten,” in Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hitlers Ostkrieg und die deutsche

Siedlungspolitik: die Zusammenarbeit von Wehrmacht, Wirtschaft und SS (Frankfurt

am Main: Fischer, 1991), 122f; 124.

Note 11: “27 July 1941,” Hitler’s Table Talk, 1941–1944: His

Private Conversations, 3rd ed., translated by N. Cameron and R. H. Stevens (New

York: Enigma, 2008), 15; cf. also Valdis O. Lumans, Hitler’s Auxiliaries: The

Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe,

1933–1945 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 212; cf.

also “Landwirtschaft im Ostraum,” DUZ 1, no. 253 (November 13, 1942) 4;

“Heimatdank für den Soldaten,” DUZ 2, no. 256 (October 31, 1943), 8, https://libraria.ua/en/numbers/875/32144/.

Note 12: Beschulung russlanddeutscher Jugendlichen, October

21, 1944, APP 53/299/0, series 3.5, file 2650, 27f., no. 30f.

Note 13: "Rede Himmlers vor dem Offizierkorps einer

Grenadierdivision auf dem Truppenübungsplatz Bitsch am 26. Juli 1944," in

Müller, Hitlers Ostkrieg, 113.

Note 14: DUZ 1, no. 216 (October 1, 1942) 3; “Landwirtschaft

im Ostraum,” DUZ 1, no. 253 (November 13, 1942), 4, https://libraria.ua/en/all-titles/group/875/.

---

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, “Warthegau, Nazism and two 15-year-olds, 1944,” History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), May 12, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/warthegau-nazism-and-two-15-year-old.html.

Comments

Post a Comment