Famine was imminent; unprecedented drought; taxes and requisitions exceeded what was harvested; some villages had no horses; extortion and arrests were widespread; many men were disenfranchised and barred from village affairs (see note 1).

Lenin responded with the 1921 “New Economic Policy” (NEP),

which allowed for a degree of market flexibility within the context of

socialism to ward off complete economic collapse.

A fixed-tax was imposed, grain quotas were eased, farmers

were allowed a small amount of land and could sell excess produce at

free-market prices after taxes had been paid.

Much was in the air. In secret talks, Soviet Trade Commissar

Leonid Krasin told the head of the Eastern Section in the German Foreign

Office, Gustav Behrendt, that the USSR was “prepared—just like Catherine the

Great of old—to call hundreds of thousands of German colonists into the land

and transfer them to large, closed complexes for settlement,” especially in

Turkestan and the North Caucasus, between the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea

west of the Caspian Sea, where the Mennonites already had several settlements.

“These colonists would be allowed to live fully undisturbed according to their

own law and create a state within a state” (note 2).

Of course nothing became of that fantastical discussion

point. Nonetheless, a time of recovery and compromise, with alliances between

government and local organizations began; the NEP-era would last until 1928.

In the Molotschna, leaders choose to form a local

“association” of about 60 villages of approximately 28,000 people which they

named somewhat artificially the “Union of Citizens of Dutch Lineage in Ukraine”

(Verband der Bürger holländischer Herkunft)—colloquially referred to as the

“Menno-Union” (Verband).

Such organizations could not be religiously based, but the

designation as a unique ethnic minority group “of Dutch lineage” allowed

Mennonites to legally organize independent of other German ethnic associations.

It came represent all 60,000 Mennonites in Ukraine.

The adopted purposes of the Menno-Union were to pursue

economic, agricultural, and “cultural” reconstruction goals, including

hospitals and possibly institutions of higher education. But for Mennonites it

was also a vehicle to recover and maintain their non-resistant tradition, and

to seek out emigration possibilities.

The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs’ (NKVD)

response to the initial statutes of the Menno-Union in December 1921 required

the removal of the word “Mennonite” and any mention of restoring the historic

Mennonite culture of the colony, of laying a moral or “religious basis” to

their economic activity, or of their connections to Mennonites of America and

Holland.

While there was a deep concern that the Union would be

“utilized for strengthening religious propaganda,” it was chartered in April

1922 (note 3).

Coinciding with this application, Mennonite leaders

organized a highly secret meeting in Ohrloff on February 7, 1922, and a

decision was taken to work to remove the entire Mennonite population of some

100,000 people out of the USSR if at all possible (note 4). And by

1926 some 20,000 Mennonites were able to emigrate.

At the same time, the goal of the Menno-Union was to revive

the economy of each village and family and their respective districts as a

whole. This had largely been achieved by 1926. Pure seed varieties had been

carefully cultivated and shared with Menno-Union members. Great attention was

given to the breeding of purebred livestock, especially the high-milk-producing

East Frisian “Red Cow” variety brought by Mennonites from Prussia over 130

years earlier, as well as to high quality pigs for the English bacon market.

Both animals were lucrative for the new smaller-sized family farms, and

appropriate for the limited grazing land available to each.

Horse breeding was less successful; in 1922 the Molotschna

had only 15% of their pre-war horse numbers. Even as late as January 1925, 30%

of farms still had no horses; 29% had one horse; 30% had two horses; 7% had

three horses; 4% had four horses. Despite a frustrating start, the number of

horses in the Gnadenfeld District increased 200% between 1922 and 1925; pigs

were up 450%; poultry up 350%, young cattle and oxen up 70%. The Red Cow

project did not grow as sharply due to the limited availability of grazing land

(note 5).

At one point during this period, my grandparents'

household—together with adult siblings--had 4 horses, 3 head of cattle, 2 pigs

and 7 sheep.

Each family could sell or trade their own products at the

village Menno-Union cooperative and connect with external markets. Shelves were

stocked, and there were employment opportunities with new mills, dairies and a

cheese factory, as well as work for blacksmiths and wood-workers. The medical

facility in Gnadenfeld became operational again, as well as the agricultural

school—both of which the Union identified as critical for community prosperity,

even if the barriers had been almost insurmountable.

“The Menno-Union appeared almost like a meteor, flashed

brightly for a moment, and then disappeared—it and the majority of men that

created it and who made it beneficial" (note 6), wrote one of the

participants, Jacob A. Neufeld. Most of the contributors, planners and

administrators of the Menno-Union were charged and imprisoned as enemies of the

state, and then exiled or executed. Neufeld stops short of calling colleagues

Mennonite martyrs; but they were for him like fallen Christian Mennonite

soldiers.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

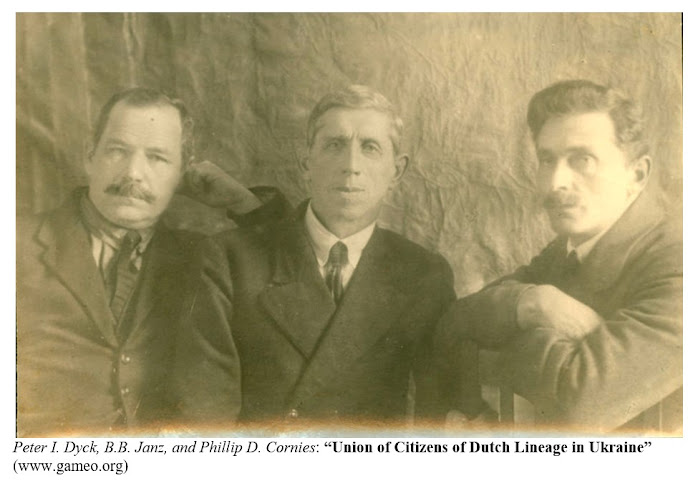

Note 1 (and pic): B.B. Janz and Ph. Cornies to Study

Commissioners to A. A. Friesen, Βenjamin Η. Unruh, C. H. Warkentin; (also) to

the General Commission for Foreign Needs of Holland; (also) to the American

Mennonite Relief, Scottdale, PA, early March 1922. Translated and edited by

Harold Bender, “A Russian Mennonite Document of 1922,” Mennonite Quarterly

Review 28, no. 2 (April 1954), 143–147; 144f.

Note 2: “Aufzeichnung des Ministerialdirektors Behrendt,” Berlin, March 2, 1921, in

Walter Bußmann, et al., editors, Akten zur Auswärtigen Politik, Serie A

(1918–1925), vol. 4: 1, Oktober 1920 bis 30. April 1921, no. 179, 382–384

(Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986), 383, https://digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs2/object/goToPage/bsb00040119.html?pageNo=435.

Note 3: See reports, responses, recommended amendments, and

final text in John B. Toews and Paul Toews, eds., Union of Citizens of Dutch

Lineage in Ukraine (1922–1927). Mennonite and Soviet Documents, translated by

J. B. Toews, O. Shmakina, and W. Regehr (Fresno, CA: Center for Mennonite

Brethren Studies, 2011), 76–98, https://archive.org/details/unionofcitizenso0000unse.

Note 4: See Janz and Cornies letter above, n.1.

Note 5: Cf. Landwirt 1, no. 4–5 (October 1925); Landwirt 2, no. 3–4 (10–11) (March–April 1926), https://chortitza.org/DPL.htm.

Note 6: Jacob A.

Neufeld, “Erinnerungen eines Beteiligten des ‘Verbandes der Bürger

Holländischer Herkunft in der Ukraine’” (Unpublished manuscript, 1952), 33. Mennonite

Library and Archives, Bethel College. https://mla.bethelks.edu/books/289_74771_N394e/. Also

translated as “Memories of the former activities of the Verband by a

participant in the Union of the Citizens of Dutch Origin in the Ukraine.”

Translated by Lena Unger. Bethel College, North Newton, KS, 1953; https://mla.bethelks.edu/books/289_74771_N394ea/.

Comments

Post a Comment