The 1930 booklet Bauer Giesbrecht was published by the Communist Party press in Germany —some months after most of the 3,885 Mennonite refugees at Moscow had been transported from Germany to Canada, Paraguay and Brazil (note 1).

In Fall 1929 Germany set aside an astonishingly large sum of

money and flexed its full diplomatic muscle to extract these “German Farmers”

(mostly Mennonites) who had fled the Soviet countryside for Moscow in a last ditch attempt to flee the "Soviet Paradise". About 9,000

however were forcibly turned back.

Communists in Germany saw their country’s aid operation—which

their crushed economy could ill afford—as a blatant propaganda attempt to

embarrass Stalin with formerly wealthy ethnic German farmers and preachers

willing to tell the world’s press the worst "lies."

With Heinrich Kornelius Giesbrecht from the former Mennonite Barnaul Colony in Western Siberia they finally had a poster-boy to make their point: in Germany he had seen and heard enough and was ready to go “back to the USSR.”

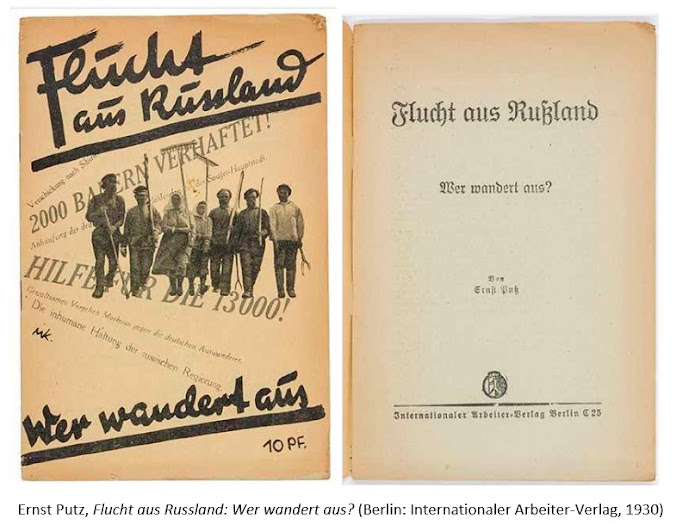

The editorial introduction by Ernst Putz frames the context

for the reader:

“In November-December 1930 it will be just one year that a similar smear campaign, taken up by old bourgeois and social-democratic newspapers, was organized around the central slogan: ‘Brothers in Need!’ Since it was conducted with extraordinary thoroughness at the time, it has not yet disappeared from the minds of hundreds of thousands of rural Germans. What was it about at that time? A few thousand families of German descent had left their villages in the Soviet Union through the systematic propaganda work of the wealthy farmers and preachers to seek their salvation in the capitalist world. … The opportunity for large-scale anti-Soviet agitation was too tempting [for the German government].”

Then Putz introduced the reader to “Farmer Giesbrecht”—pictured on the cover (pic), smiling, with his accordion—who, once in Germany, “soon realized how deceived they had been when the wealthy farmers and preachers in their Siberian villages promoted the world outside the Soviet Union to them painted in the rosiest of colors.” Not only was Giesbrecht unhappy with what he was seeing, but the preface adds excerpts from two letters from two Mennonites already in 'the promised land." The first letter is from the new northern Ontario hamlet of "Reesor"—carved out of the forest by new Mennonite settlers—and the second from Brazil.

"Between you and me, you don't know how badly I'm doing

here. I have already visited Hermann, and he’s not doing well either. So far he

hasn't earned anything. Our uncle lives here in the forest, and this is his

life; it's very lonely, no roads to drive, only to walk, and walking is also

very difficult. It is very wet; this is virgin forest, and as far as you can

look you can see no end. There are also a lot of mosquitoes that almost eat you

up. They always have to smear themselves [with repellant] when they go to work.

And in order to sleep, you have to fumigate inside. It is like this for two

months and then it freezes again and they stop. I have never seen such a place.

Here you can’t even keep a cow; there is no pasture and no garden. Everything

freezes. Life is very costly." (Letter from Reesor, Ontario, dated August

28, 1930)

"Oh, pioneering here is so hard here—so hard, that only

he who has seen it can really understand. Should you have the great fortune to

return, oh, then I will rejoice with you." (Letter from Brazil, Estado

Santa Catharina, dated July 27 [1930])

None of this sounds fabricated. For the editor and others, the letters are testimony to the

“unspeakable misery that the emigrants experienced abroad” (note 2).

In the main text of the pamphlet Giesbrecht first describes

his village and then recounts his flight to Moscow from western Siberia. It is

similar to many other stories in the same months, for

example, and also does not sound fabricated (note 3).

“Our village is purely Mennonite. They keep themselves

strictly separated from others, but nevertheless our village is not so much

religious, except for a few.” [After Giesbrecht’s longer account, editor Putz

concludes:] “The farmer, having had such experiences in Germany and having read

such letters from [North and South] America, decided to return [to the USSR] in

order to do all he could for the socialist reconstruction [of the USSR].”

This was a small propaganda victory for German

communists—and the pamphlet was distributed in Mennonite circles as well. A

certain Jacob Thiessen wrote to the Canadian Mennonitische Rundschau early in 1931 about

the remaining Mennonite young adults in the USSR with reference to this

pamphlet:

“They are not so rooted in the faith of their fathers; they

are more easily inspired by the vision of the ‘building of a new [socialist]

world; moreover they have not known the former Russia. It may be that the youth

will be forced to deny the Christian faith and join communism. Unfortunately

however, the fact is that many go over to communism out of inner conviction. I

need only remind you of the booklet published by the International Workers'

Publishing House in Berlin: Bauer Giesbrecht migrates back to Siberia. This

Mennonite refugee came to Hammerstein during the mass exodus of 1929, but

realized that in Germany and, of course, in other capitalist countries, the

situation of small farmers and workers was much worse than in Russia, and with

the help of the German communists he migrated back to Russia. Unfortunately,

many similar cases are known to me from credible sources.” (Note 4)

The letter confirms what newer research tells us: many

ethnic Mennonites ca. 1930 were embracing Soviet socialism.

But that is not the end of the “Farmer Giesbrecht” story.

Giesbrecht retuned not only to his village of Alexandrowka sometime after September 1930 (pic), but also to his wife and children who had been forcefully returned from Moscow in November 1929.

Their village was only 20 km from the location of another

story we have told, namely of the Mennonite uprising and hostage-taking of

Communist managers in Halbstadt/Barnaul in July 1930. The rebellion was led by

Katharina Siemens (note 5), 2 ½ months before Giesbrecht's return to the

district in September.

Halbstadt was the Barnaul /German District centre (see map

pic). The uprising started when Johann Martin Winter, a “kulak” emigration

leader from Giesbrecht’s village of Alexandrowka had been sent back from Moscow

in December with hundreds of others unable to emigrate, was arrested locally on

July 2, 1930 (our Heinrich Giesbrecht had managed to get to Germany). On the

night of Winter’s arrest, David Isaac Giesbrecht [relation to Farmer Heinrich

Korn. Giesbrecht unclear] notified all the other villages in the German

District to come to the district centre in Halbstadt to help secure Winter’s

release.

It is an amazing drama (see note 5).

In the end, David Giesbrecht and Johann Winter with others

were tried on August 31, 1930, and Winter was executed by shooting October 22,

1930—near the time of “Farmer Giesbrecht’s return from Germany. The others were

sentenced to various terms of imprisonment (note 6).

What was the fate of the German communist poster-boy, Farmer

Heinrich Kornelius Giesbrecht?

He was arrested in 1934 for sabotaging the grain harvest and

grain procurement, together with others (including his daughter). After

investigation, the group objectives were found to be:

a) in propagandizing the ideas of German fascism among

ethnic Germans in the district and to converting the latter into active

supporters of Hitler's movement in Germany;

b) in protecting the Kulaks [the formerly wealthy] and

promoting them to leadership roles in the collective farms to undermine the

latter; and to sabotaging the grain harvest and the state’s grain procurements

for 1934;

c) in creating favourable conditions in the district for the

spread of so-called "Hitler-Aid" coming from abroad and engaging in

fascist agitation around the receipt of such aid." (Note 7)

Giesbrecht was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment (note 8;

pic). His case, together with the others arrested that year, was officially

overturned in 1960 because of "fabrication" and "lack of

evidence."

We do not know if "Farmer Giesbrecht" survived his

prison term. This was his reward for returning to help build the new Soviet

socialist society. His story is as fascinating as it is tragic. It offers a window

onto the confusion among younger adults in a changing context, and onto the

heavy oppression through the 1930s based on fabricated evidence.

(Giesbrecht's sister, Elisabeth Giesbrecht Rempel, and his brother-in-law arrived in Canada earlier in Fall 1929; see note 9).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Map pic: https://www.mennonitechurch.ca/programs/archives/holdings/Schroeder_maps/150.pdf.

Note 1: Heinrich

Kornelius Giesbrecht, Bauer Giesbrecht wandert zurück nach Sibirien. Erlebnisse

eines mennonitischen Rußlandflüchtlings, edited by Ernst Putz (Berlin:

Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, 1930), https://web.archive.org/web/20240202182741/https://shokei.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/764/files/MA103N.pdf. Though some 9,000 Mennonites had

reached Moscow, only 3,885 Soviet Mennonites plus 1,260 Lutherans, 468

Catholics, 51 Baptists and seven Adventists were cleared to leave; cf. Cf.

Detlef Brandes and Andrej I. Savin, Die Sibiriendeutschen im Sowjetstaat

1919–1938 (Essen: Klartext, 2001), 287.

Note 2: Agrar-Probleme, issued by the Internationales

Agrar-Institut Moskau, vol. 4 (Moscow / Berlin: Parey, 1932), 185, https://books.google.ca/books?id=uiw9AAAAYAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=gie sbrecht. Another booklet in the same series and

by the same editor as Bauer Giesbrecht describes a visit to Molotschna villages

ca. 1931/32 by farmers from Germany. It is a promotional tour to convince

farmers from Germany of the virtues of agricultural life under communism. Ernst Putz, ed., Deutsche Bauern in

Sowjet-Rußland (Sinntalhof/Rhön: Putz/ Reichsbauernkomitee, 1932), https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bibliothek/bestand/a-36261.pdf. For shorter published accounts about dissatisfied Mennonites abroad, see for example Fedor M. Putintsev, Enslaving Brotherhood of the Sectarians

[Кабальное братство сектантов], Central Council of the Union of the Militant

Atheists of the USSR (Moscow: OGIZ, 1931), excerpted at: https://chortitza.org/pdf/vpetk265.pdf. See also Ernst Putz, Der Bauer und dem Traktor: Kollektivwirtschafen und Staatsgütern in der Sowjetunion (Berlin: Internationaler Arbeiter-Verlag, 1930); other of this genre scanned here.

Note 3: See my other posts, e.g.,

Notes 4: Jakob

Thiessen, Mennonitische Rundschau 54, no. 12 (March 25, 1931), 7, https://ia902305.us.archive.org/17/items/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1931-03-25_54_12/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1931-03-25_54_12.pdf.

Note 5: On the July 1930 Halbstadt/Barnaul uprising and hostage-taking of communist managers, led by a Mennonite woman, see previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2022/09/mennonite-rebel-leader-executed.html.

Note 6: The above is pieced together from Abram A. Fast's

research supported by archival materials from the Centre for Preservation of

Archival collections of Altai kra. His book's title: V setyakh OGPU-NKVD:

Nemetskiy rayon Altyskogo kraya v 1927-1938 gg (Slavgorod: Slavgorod

Publishing, 2002), https://chortitza.org/Dok/FastR.pdf.

The section on the "Halbstadt (Barnaul) Rebellion" begins on p. 57,

and is very well documented.

Note 7: Document 7, in A. Fast, V setyakh OGPU-NKVD, 171f. The

aid packages from Mennonite relatives in North America came over Germany and

the office of Benjamin Unruh. See previous post (forthcoming).

These were later deemed as "Hitler help" and recipients were easy to

identify as "enemies of the state."

Note 8: See Document 12, in A. Fast, V setyakh OGPU-NKVD,

186-195; Giesbrecht on pp. 189 and 195 –(DeepL and Google Translate).

Note 9: See Elisabeth Giesbrecht Rempel obituary, Mennonitische

Rundschau 94, no. 11 (March 17, 1971), 11, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1971-03-17_94_11/page/11/mode/2up;

Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization card for Johann and Elisabeth Rempel, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/5300s/cmboc5341.jpg;

GRanDMA #349299. They were the earliest ones to leave Moscow in 1929; cf. https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_91/folder_2/SKMBT_C35107121009320_0021.jpg.

Also brother to Kornelius Korn. Giesbrecht, #516241; see passenger lists to

Brazil, 1930, https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/latin/Mennonite_Passenger_lists_for_Brazil.pdf,

and Rundschau 53, no. 2 (January 8, 1930), 6, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1930-01-08_53_2/page/6/mode/2up

and https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1930-02-19_53_8/page/n1/mode/2up?q=giesbrecht.

Comments

Post a Comment