The following propaganda photos are of the Mennonites community in Chortitz, Ukraine during German occupation in World War II.

German armies reached the Mennonite villages on the west bank of

the Dnieper River on August 17, 1941. The photos below were taken almost two

years later. However the war was already turning, and within two months the

trek out of Ukraine would begin.

The photographs are accompanied by an article about the

Low-German speakers of Chortitza for a readership in the Reich (note 1).

The author repeatedly draws on the myth of one-sided

German pioneer accomplishments abroad: “The first settlers found the land

desolate and empty,” the reader is told, and were “left to fend for themselves in a foreign

environment” where with German diligence, order and cleanliness they thrived.

The article correctly recognizes the great losses of the

ethnic Germans under Bolshevism--as if to convince readers that the war is a

shared burden of all Germans, and which is now paying off. Readers can see with

their own eyes: “German villages can once again be found along the Dnieper”

that are “German in appearance and cleanliness.”

It is a Blut und Boden article--highlighting not only the

lack of land and justice for Germans (consistent with other Nazi propaganda

messaging), but also German blood: namely, "its" historic achievements and

reslience, but also "its" future in the youth of the east.

The many children typical in these Chortitza famlies is praised and

given special attention. Now not only do these youth sing German folk songs again as in

generations past, but children also participate joyfully in the "Hitler

Youth and grow firmly and indissolubly into a new Reich worldview.”

Churches--which the Nazis recognized as being key

instituions for preserving German language and culture in the East--are no

longer Bolshevik cinemas but places of worship again. The readers are also told of the 80 ethnic German

teachers that have been trained and placed in schools, competent in the method

and content of the Reich's curriculum.

As a climax to the article, it concludes with a promising

report for its readers: On April 20, 1943, “200 boys and over 200 girls were

accepted into the Führer's Youth [Hitler Youth and League of German Girls].

‘Into the east wind raise the flags,’ their voices sang brightly into the

spring sunshine. The boys and girls are the heirs of the first German colonist

blood in the East ...”

The photographs below seek to capture and communicate all of this. The captions are also translated:

"I received a first, wonderful mission in life in Chortitza,' explains the young League of German Girls leader from Saxony. She is the best comrade of the boys and girls and laughingly teaches them what they need to know and learn."

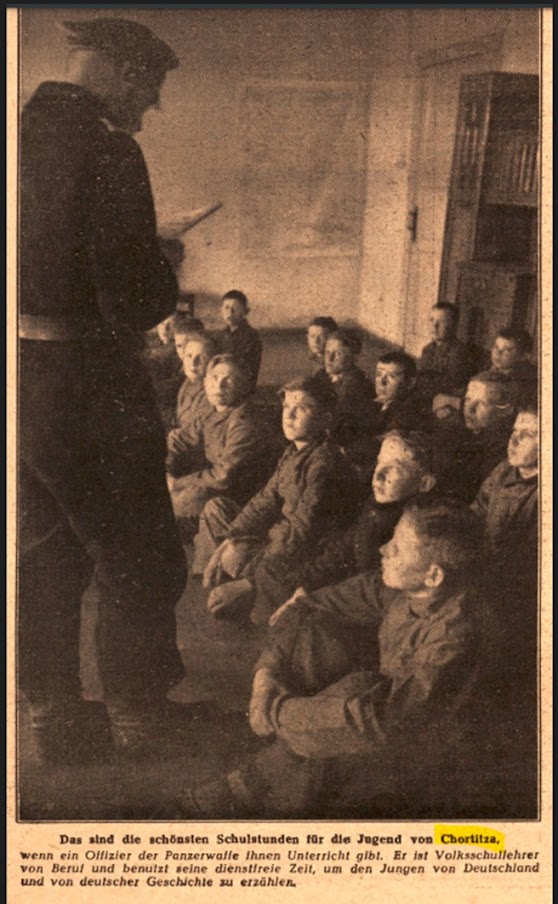

"These are the most wonderful instructional times for the youth of Chortitza, when an army tank officer comes in to teach. He is an elementary school teacher by profession and uses his off-duty time to tell the boys about Germany and German history."

"'But we had our children,' explains the young

wheelwright's wife. 'For them we persevered, even though we suffered terribly

under the Bolshevik terror and sometimes didn't know what to do.'"

"Joy of life shines from their eyes again. The girls and boys have developed splendidly since the village has been under German administration. Healthy, cheerful and energetic, freed from Bolshevik enslavement, they are growing up, a new generation of the best German farmers and settlers."

"In the closing years of a fateful life the old farmer's wife, now under the protection of the German Wehrmacht, can once again be calm and confident again. The suffering that she has experienced in the past years dissolves in a kind smile."

"The wheel whirrs. Spinning wheels can be found in almost in almost every living room. In times of need they were the only source of income for many families."

"The well. Every German farm in Chortitza has its own wood-lined well, which is kept scrupulously clean."

"Gardens, fruit trees and clean houses--these are the

hallmarks of the German farms in Chortitza on the banks of the Dnieper.

Diligent hands have restored the settlements to what they were before Bolshevik

rule: exemplary examples of German colonist labour."

Likely Mennonites in Ukraine did not see these powerful

propaganda photographs or read the article. But there is every reason to think

that they would have felt honoured by the favourable portrayal, and encouraged

and duty bound to continue to grow into the new (and old) myths it projected (note

2).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Joachim Preß, "Deutsches Dorf am Dnjepr: Vom

Wiederaufbau nach der Bolschewisten Herrschaft," Schlesische Sonntagspost 14,

no. 30 (July 25, 1943), 6-7, https://sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/349438/edition/330187/content.

Note 2: See other Chortitza propaganda shots in previous

posts: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/hans-p-epp-blumengart-teacher-minister.html;

also https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/chortitza-greets-reich-minister-for.html.

---

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "German Village on the Dnieper: Occupation Propaganda Photos. Chortitza, 1943," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), December 3, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/12/german-village-on-dnieper-occupation.html.

Comments

Post a Comment