In 1926, my grandfather’s sister Justina Fast (b. 1896) and her husband Peter Görzen moved from Krassikow, Neu Samara (Soviet Union) to village no. 5 Dejewka, Orenburg. “We thought we would live our lives here with our children secure in the hands of God. But the times were becoming turbulent,” Justina recalled. In May 1929 they travelled back to Krassikow for Pentecost to visit with her mother, brothers and their families. But when they returned to their home, she writes,

“… a large quota of grain was demanded of us. But we had nothing, and the harvest was not yet in. Then we heard that many were planning to move to Canada, including my three siblings with my mother, and my husband's three sisters too. My husband decided to go to Moscow first to see if it was possible and what was required for emigration. We made the decision to leave when the harvest was complete. At that time so many people were leaving [for Moscow], and early in September we sold everything we had. Only the beautiful house we were unable to sell; we left it standing, and I shed many tears over this. Immediately after the sale we left for Moscow [1,300 km]—early in September 1929. We expected to be out of the country soon thereafter, yet things did not happen as fast as we were expecting. There were so many families arriving in Moscow every day, that authorities gathered us in the street, asked what we wanted and who the instigator or group leaders were. People came from every direction, and all wanted to go to Canada.” (Note 1)

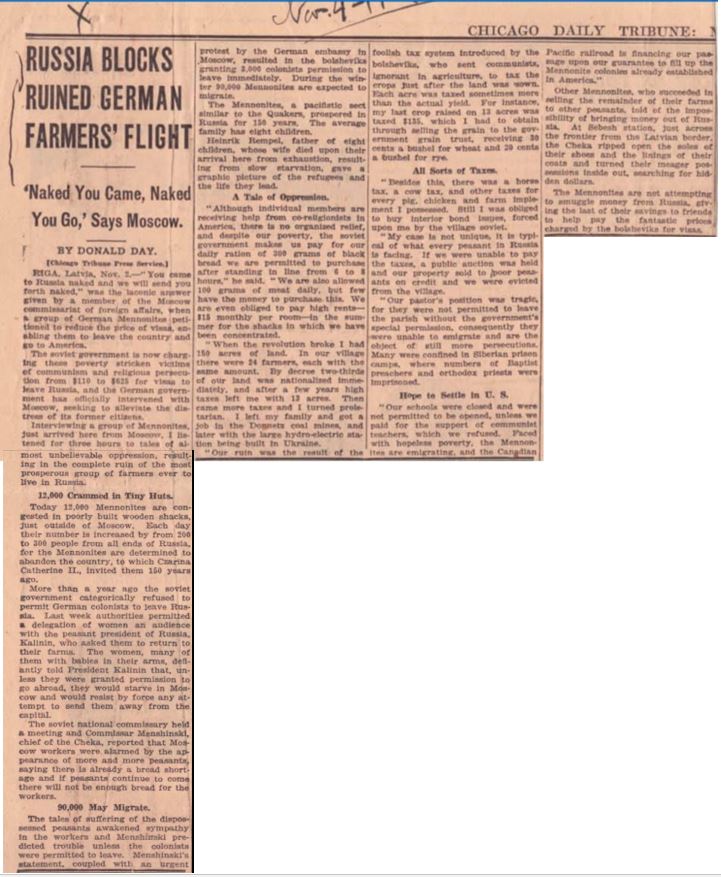

It was a desperate act of resistance to Soviet

collectivization, education and religious policy that brought over 9,000

thousand Mennonite farmers to Moscow in fall 1929, together with another 4,000

German Lutherans and Catholics, with a small number of Baptists and Adventists

(note 2).

The real economic growth they achieved in Ukraine and Russia

under Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) since 1921 with small-scale agriculture

and all-Mennonite organizations had come to a quick end with Stalin’s

solidification of power in the late 1920s.

The Stalin group’s “revolution from above” abandoned the

limited free market capitalism of the NEP era, imposed rapid collectivization

and large-scale mechanization of agriculture, announced the liquidation of

wealthy peasants (kulaks) as a class and the elimination of all free market

sales of grain, livestock or handicrafts, introduced low fixed prices for

products, and enforced impossible quotas with heavy fines and imprisonment for

non-compliance (note 3). All of this was designed to bring already desperate

small farmers to a quick breaking point, and to bring to an end the traditional

household economies of Mennonites and other farmers in Ukraine and Russia.

Mennonites spoke frequently of their “spiritual distress.”

They accepted the removal of religious instruction from their schools only very

reluctantly, and were appalled at the “anti-religious propaganda” that took its

place and with the restrictions on public religious observance and teaching. “We must get out of this country if we do not want to allow our children to go

to utter ruination economically and spiritually,” Halbstadt Elder Abram Klassen

wrote to his Canadian counterparts (note 4).

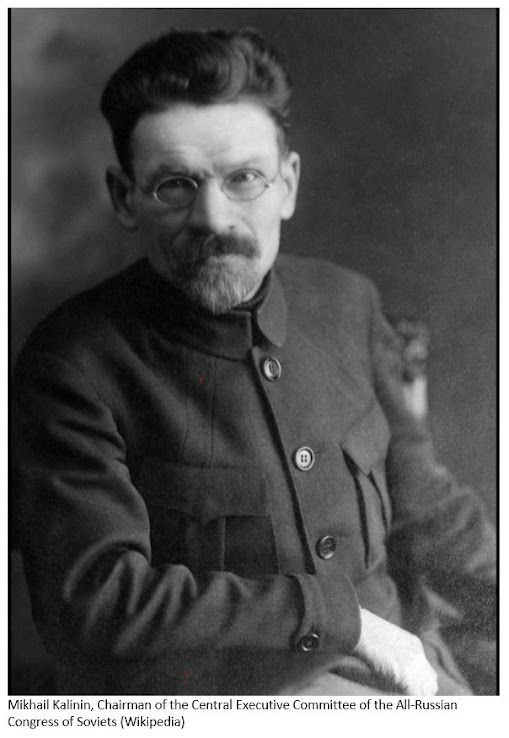

In early summer 1929 news of a crack in the state’s restrictive emigration policy spread through Mennonite villages across the Soviet Union: twenty-five Mennonite families had received exit visas. They had made a personal request to M. I. Kalinin, President of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and, only “after much urging and support” from the Chair of the Moscow Soviet Pyotr Smidovich, successfully left the Soviet Union. But “it was emphasized very strongly that under no circumstances would any further groups be allowed to depart in the next years,” according to Benjamin H. Unruh, spokesperson for Russian Mennonites in Germany and for the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization in Europe, who guided their departure (note 5).

Yet by

mid-June Unruh was scrambling to find sponsorships in Canada for another

seventy-four families. This news circulated and by the end of October more than

6,000 people—perhaps double, and largely Mennonites from Siberia—with

belongings in hand descended upon Moscow in a massive flight attempt (note 6).

Confident of support from relatives and coreligionists abroad and of the

diplomatic goodwill of Germany, the would-be emigrants disposed of all their

assets—mostly at rock bottom prices—and fled for Moscow.

The German embassy followed the dramatic developments in

Moscow closely; since Germany’s humiliating defeat and territorial loss in the

Great War, an emerging German identity as an ethno-cultural Volk across

national borders and institutions had taken on a new imagined reality, which

inspired strong loyalty toward beleaguered German minorities in the east (note

7). In this context, not only did the German embassy insist that the Soviet

Union respect the rights of ethnic German farmers, but letters from private

citizens requesting intervention inundated the Commissariat for Foreign Affairs

(note 8). “The fate of these pioneers and colonists is very German and touches

on the deepest questions of our ethnic peoplehood (Volkstum) in general,” one

Berlin paper argued (note 9).

German ambassador in Moscow Herbert von Dirksen did not support asylum in Germany; this move could trigger a powerful attractional force for the remaining German farmers and their families in the Soviet Union (note 10)—as many as 700,000 or 800,000 individuals. These would be impossible to assimilate or resettle—though Nazi Germany would try to do this very thing ten years later with annexed Polish lands.

Rather, since 1922 Germany aimed to give only enough aid to Germans in the Soviet Union to squelch any desire for mass emigration (note 11). Von Dirksen even outlined in an August 1929 confidential memo the political value of ethnic Germans in Ukraine as a support base (Stützpunkt) for any future German ambitions, including the promotion economic and cultural ties (note 12). Five years earlier the German Consul in Ukraine had worked to block a mass evacuation of Mennonites for much the same reasons (note 13). To Germany’s embarrassment and to the danger of Mennonites in 1929 and later, much of this secret diplomatic correspondence had been leaked to Soviet sources and published mid-November (note 14). Nonetheless in August 1929 von Dirksen advised his department that immigration—if possible—should not be to Germany; maybe Canada or, if that path is blocked, to Paraguay or Chile. Canada was problematic for him insofar as farmers are settled in “checkerboard style, which is without a doubt a threat to the preservation of Germandom” (note 15). However Unruh was assured by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) office in Hamburg that transit credits for Mennonites to Canada were available at the Russian Canadian Trade Association in Moscow (RU-KA-PA; note 16).

Peter and Justina Görzen had been in Moscow for a month when

they wrote her siblings and mother “that the Russian government will allow

[Mennonites] to emigrate.”

Peter Görzen was arrested in Moscow in 1929 and Justina and

children remained behind. Her mother and siblings were successfully evacuated

to Germany. I was privileged to correspond with her (living in Podolsk) in the

early 1980s. She was able to tell me about my grandfather whom I had never met

and their early life in Neu Samara.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: “Lebensverzeichnis unserer lieben Mutter, Justina

Görzen, geborene Fast.” Annotated translation by Arnold Neufeldt-Fast: “Early

Years and Flight to Moscow (1929). Autobiography of Justina Fast Görzen (Part

I).

Note 2: For documentary links between the flight and local

protests and mass resistance towards collectivization and dekulakization

amongst Siberian Mennonites, cf. Detlef Brandes and Andrej I. Savin, Die

Sibiriendeutschen im Sowjetstaat 1919–1938 (Essen: Klartext, 2001).

Note 3: Cf. R. W. Davies, “Stalin as Economic Policy Maker:

Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1936,” in Stalin: A New History, edited by Sarah

Davies and James R. Harris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 121f.

Note 4: Abram Klassen, letter July 1, 1928, translated in David

Toews to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, August 15, 1928, letter,

from MCC-Akron, IX, box 3, file 7.

Note 5: Benjamin H. Unruh to Peter Braun, October 29, 1929,

1, letter, from Mennonite Library and Archives-Bethel College, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_91/folder_2/.

Note 6: See Harold Jantz’s comprehensive collection and

translation of related materials: Flight: Mennonites facing the Soviet Empire

in 1929/30, from the pages of the Mennonitische Rundschau (Winnipeg, MB: Eden

Echoes, 2018).

Note 7: Cf. Rogers Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed:

Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1996), 117f.

Note 8: Cf. Lynne Viola, Peasant Rebels Under Stalin:

Collectivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), 261, no. 109.

Note 9: Bernhard Lamey, “Richtung Moskau—Kanada,” Vossische

Zeitung, no. 522, November 5, 1929, 4 (link).

Note 10: Curtius to the State Secretary of the Chancellery,

November 6, 1929, in Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik 1918–1945, Serie

B: 1925–1933, vol. XIII (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1979),

227, no. 104 (link). On the fear of mass migration of Russian Germans, cf. James E. Castel, “The

Russian Germans in the Interwar German National Imaginary,” Central European

History 40 (2007), 455; Erwin Warkentin, “The Mennonites before Moscow: The

Notes of Dr. Otto Auhagen,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 26 (2008), 209 (link).

Note 11: Documented in Maria Köhler-Baur, “Die deutsche

Berichtserstattung über die Rußlanddeutschen. ‘Der Auslandsdeutsche’

1920–1929,” in Deutsche in Rußland und in der Sowjetunion 1914–1941, edited by

A. Eisfeld, V. Herdt, and B. Meissner (Berlin: LIT, 2007), 209f.

Note 12: Herbert von Dirksen to German Foreign Affairs, August 1, 1929, in Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik, Serie B: 1925–1933, vol. XII (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978), 306 n.2, no. 141 (link). The German press echoed this interest; cf. Bernhard Lamey, “Richtung Moskau—Kanada: Deutsche irren durch die Welt,” Vossische Zeitung, no. 522, November 5, 1929, 4 (link). Generally, cf. Casteel, “Russian Germans in the Interwar German National Imaginary,” 448; 451.

Note 13: B. B. Janz, in John B. Toews, The Lost Fatherland:

The Story of the Mennonite Emigration from Soviet Russia, 1921–1927 (Scottdale,

PA: Herald, 1967), 162 (link).

Note 14: W. Zechlin to State Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Schubert, November 14, 1929, in Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik, Serie

B, vol. XIII, 263f., no. 123. The leak was published in the Berlin-based

pro-communist paper Die Rote Fahne (“Die Not der Deutschen in der USSR ein

entlarvter Wahlschwindel!”), no. 231 (November 14, 1929), 1.

Note 15: Dirksen to Foreign Affairs, August 1, 1929, in Akten

zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik, Serie B, XII, 307, no. 141.

Note 16: Cf. Benjamin Unruh, November 1929, 1b, 2 [check];

idem, “Bericht II: Über Verhandlungen in Berlin, vom 19.10 bis 24.10.,” October

25, 1929, 2 (report), to Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization. From

MCC-Akron, IX-02, box 4, file 4. Cf. also Jochen Oltmer, Migration und Politik

in der Weimarer Republik (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005), 199,

206 (link);

Henry J. Willms, ed., At the Gates of Moscow, translated by George G. Thielman

(Yarrow, BC: Columbia, 1964), 133 (link).

Comments

Post a Comment