Asiatic Cholera broke out across Russia in 1829 and ‘30, and further into Europe in 1831. It began with an infected battalion in Orenburg (note 1), and by early Fall 1830 the disease had reached Moscow and the capital. Russia imposed drastic quarantine measures. Much like today, infected regions were cut off and domestic trade was restricted.

The disease reached the Molotschna River district in Fall

1830, and by mid-December hundreds of Nogai deaths were recorded in the villages

adjacent to the Mennonite colony, leading state authorities to impose a strict

quarantine.

When the Mennonite Johann Cornies—a state-appointed

agricultural supervisor and civic leader—first became aware of the nearby

cholera-related deaths, he recommended to the Mennonite District Office on

December 6, 1830 to stop traffic and prevent random contacts with Nogai. For

Cornies it was important that the Mennonite community do all it can keep from

carrying the disease into the community, though “only God knows our destiny” (note

2).

On December 30, 1830, Cornies reported the situation to his

Mennonite friend Johann Wiebe in Tiege, West Prussia. He noted the actions they

had taken, but also offered a theological framework for understanding their

crisis.

“God alone knows what will befall us in this sad time. Our

villages exist like an island in an ocean of cholera, and there is evil all

around. ... We have taken the following precautionary measures.

In every village, two men visit each house daily to check on

the family’s health. To separate the sick from the healthy, one house has been

emptied for use as a hospital. A large bathtub, etc. stands beside each Village

Office.

We do not know what the future holds. Only the Eternal can

see it. We must build on His grace and plead with Him to turn this scourge away

from our empire and our villages.

With complete faith in the wisdom of our government, we

await the Almighty’s ordinances without fear.

May every Christian, every thinking person harbour the

personal conviction that whatever comes from God will serve our well-being. May

this supreme wisdom divinely illumine man’s immortal spirit, created in His

image, and cast light into the darkness of our earthly path.

We do not strive against God’s will by using our minds in

taking precautions against disease and in battling disruptive natural forces.

We are using our talents from on high, submitting them to His wise counsels and

thereby praising His holy name. As you know, some people here consider

precautionary measures to be sinful. Others continue to indulge in frivolity,

even in this depressed, discouraging time.” (Note 3)

Cornies praised the state’s self-distancing measures:

“All roads are blocked and no one is allowed through without undergoing quarantine. It is impossible to thank God enough for His fatherly guardianship of our administration, which protects us through its wise measures” (note 4).

“If we follow these regulations scrupulously, the only thing

left for us to do is to pray honestly and to submit to God’s Will” (note 5).

Within a few months, the pandemic broke out in the city of

Danzig as well, despite a 20-day quarantine on individuals and goods coming

from Russia. On June 16, 1831, Prussia began to treat vessels proceeding from

Danzig “as if coming from Russia” (note 6).

The Mennonite and German colonies of the region were spared

a cholera outbreak. September 18, 1831: “Until now our community has been

spared, although we have felt ourselves under siege since May … I consider no

doctor to be God and no medicine as Saviour, but I firmly believe that if God

does not give His blessing to our daily bread or our medications, they will

neither nourish us nor heal us” (note 7).

During the German occupation of Ukraine in 1942 was the

following 1831 vaccination record was found: “Table on Vaccination of Children

in the Districts of Chortitza and Molotschna” (note 8). Unfortunately, the

document itself appears to be lost.

Vaccinations for Mennonites were not new; good cow pox

immunization records for children in Chortitza in 1809 and 1814 are available (note

9).

Johann Cornies’ reading of scripture makes him confident

that the Tsar’s response—including vaccination encouragement—is divinely led.

"[T]he Lord has power over all human hearts and directs

them as He wishes, guiding them like water in a brook [cf. Proverbs 21:1]. In

this way He also directed the loving father of our country to go to Moscow to

take measures that would ease the suffering. Many others followed his lead with

significant acts of benevolence and support for the poor. We give God a thousand

thanks." (Note 10)

Reason, prayer and hope in the emperor are three strands of one cord for Cornies. The pandemic took some 250,000 lives in Russia, with a fifty-percent mortality rate among those infected (note 11).

The global dimensions of the pandemic, the large numbers of

deaths, the state enforced quarantines, the crippling economic consequences,

the existential fear of death—all of these aspects bear a striking resemblance

to our own times. Perhaps there is something to learn from the spirituality of

the time as well.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Pic 1: Johann Cornies

Pic 2: Nogai village, in Daniel Schlatter, Bruchstücke

aus einigen Reisen nach dem südlichen Rußland in den Jahren 1822 bis 1828 (St.

Gallen, 1830), 74, https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/content/zoom/7886108.

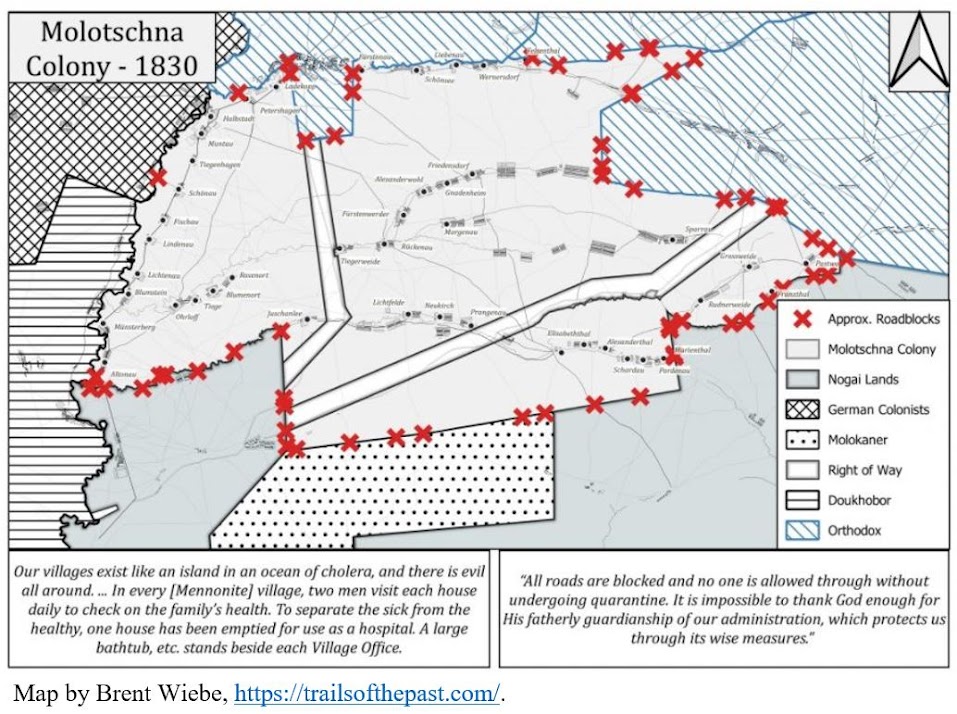

Map: Courtesy of Brent Wiebe; see his important website (especially for map collections) and the illustrations to my related article, https://trailsofthepast.com/2020/08/07/mennonitesepidemics/.

Note 1: John P. Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera,

Disease under Romanovs and Soviets (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2018), 40.

Note 2: Cornies to Molotschna Mennonite District Office,

December 6, 1830, in: Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters

and Papers of Johann Cornies, vol. 1: 1812–1835, translated by Ingrid I. Epp;

edited by Harvey L. Dyck, Ingrid I. Epp, and John R. Staples (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 2015), 198, no. 198.

Note 3: Cornies to Johann Wiebe, Tiege, West Prussia,

December 30, 1830, in Transformation I, 205, no. 202.

Note 4: Cornies to Blueher, December 10, 1830, in Transformation

I, 200, no. 200.

Note 5: Cornies to Andrei M. Fadeev, Dec. 22, 1830, Transformation

I, 202, no. 201.

Note 6: History of the epidemic spasmodic cholera of Russia (London:

Murray, 1831), 245f. https://archive.org/details/b22478371/page/246/mode/2up.

Note 7: Cornies to Jacob van der Smissen, September 18,

1831, in Transformation I, 244, 239.

Note 8: Records of the National Socialist German Labor Party

(NSDAP), National Archives Microcopy, no. T-81, roll 606, image 5396345.

Deutsches Ausland-Institut, file 1397. American Historical Association.

American Committee for the Study of War Documents. Washington, DC, 1956.

Scanned on FamilySearch.org records, image 639 of 1,309, https://www.familysearch.org/records/images/image-details?page=1&place=5337&endDate=1942&startDate=1942&rmsId=TH-909-64122-19191-56&imageIndex=638&singleView=true&fbclid=IwAR2a1h4O-gjFi-CdKONW8Co5P31hOdWdIOloc7VSR0TUxbh4y-FoVwVD6f0.

Note 9: See previous post on vaccinations 1809 and 1814 (forthcoming);

see also for the plague in Danzig, 1709, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/plague-and-pestilence-in-danzig-1709.html;

and also Spanish Flu, 1918 and its impact on Mennonites, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/03/spanish-flu-pandemic-in-ukraine-and.html.

Note 10: Cornies to Blueher, 10 December 1830, in Transformation

I, 205, no. 200. Cornies also uses this Proverb in correspondence to Wilhelm

Frank, March 10, 1826 (no. 51, p. 59) as does Elder Bernhard Fast to Cornies,

February 16, 1827 (no. 97, p. 115).

Note 11: Davis, Russia in the Time of Cholera, 42.

---

To cite this post: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "A Mennonite Pandemic Spirituality, 1830-1831," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), May 29, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/a-mennonite-pandemic-spirituality-1830.html.

Comments

Post a Comment