When Helene (Thiessen) Bräul and daughter Käthe arrived at the Malton-Toronto Airport from Paraguay on May 29, 1955, Helene was fifty-one years old. With many of her friends, she struggled with the inhospitable Paraguayan Chaco for eight years. Their husbands had all been shot in Ukraine seventeen years earlier. Käthe (my mother) was seventeen-and-a-half—robbed of a normal childhood, but ready and hopeful for new beginnings. Neither knew English and they arrived as poor as when they left war-torn Europe in 1947: one suitcase each, but now with a travel debt as well. Mennonites in Paraguay had survived the worst because of a rich global church network of support (note 1).

While Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) and the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization (CMBC) did not provide financial assistance for immigration to Canada from South America, they did assist with immigration procedures and travel arrangements. Canadian immigration officials did background checks of applicants both in Paraguay and Europe.

CMBC Chair J. J. Thiessen also made multiple “personal”

representations to the Canadian government on behalf of Mennonite men from the

Soviet Union in Europe (and some in Paraguay) who had joined the German

Waffen-SS—including Thiessen’s own nephew. Helene’s two eldest sons were in the

same cavalry squadron, but missing in action.

In 1955 there was a huge government backlog in processing

sponsored applicants—77,158—and approvals took on average one year. Helene and

Käthe were among 109,946 immigrants to Canada in 1955 (note 2).

The Bräuls were brought to the Jordan and Vineland area

(Niagara), the location of the very first Mennonite settlement in Canada in

1786—coincidently, the same year that Mennonites in Polish-Prussia were negotiating

terms with Catherine the Great for the creation of a Mennonite settlement in New

Russia.

On paper Helene was sponsored from Paraguay under Canada’s

generous “Close Relatives” scheme by her sister Maria Thiessen Braul and family

in Alberta. But it was her cousin in Jordan Station who could advance the full

air fare of approximately $650 per person, and offer accommodations and work

for Helene and Käthe on their fruit farm.

Most immigrants from Paraguay settled either in Niagara, Leamington, Winnipeg or in the Fraser Valley in British Columbia (note 3). Demand for Canadian fruit and vegetable products during the war years allowed Mennonite farms in Ontario and B.C to flourish. The relatives in Alberta thought correctly that it would be physically easier for Helene to work on a fruit farm than to hoe beets on the Alberta prairie (note 4); in the Soviet Union and in Paraguay many women had done physical labour far beyond what their bodies could in fact handle and with the most primitive equipment. The Niagara region was particularly attractive because of its job opportunities and its network of Mennonites and their institutions (note 5).

Helene’s cousin offered a room in their house on their

thirty-two-acre fruit farm. The room had one double bed which Käthe and Helene

shared and a table. The room was so small that their two suitcases had to be

stacked one upon the other.

Like so many immigrants to Niagara, Helene became a farm labourer upon arrival. She began work at 6 AM, and long hours were expected. She had to pay for her room and board, and repay the full amount of the airfare. In one year of farm labour, a fellow immigrant with a similar life-story recorded (a few years later) earnings of $7,312: “1962: Worked on the Janzen farm … earned $5,192 (hourly), plus $1,142 for strawberry picking; $98 grape cutting; in total earned $7,312.” The immigrant women earned 6 cents per quart of strawberries and 25 cents for a bushel of grapes (note 6). Those who could pick fast the whole day, earned good money. Within one year Helene had completely paid off her travel debt to her cousin and was ready to move on. Pruning fruit trees in the cold of winter was too much for her body; in the first year, she developed a kidney infection and was told by her doctor to discontinue outside winter labour.

She and Käthe then moved from Jordan Station to nearby

Vineland where they found an apartment on First Street, in walking distance

from the Vineland United Mennonite Church and other amenities. The owners—a

Derksen family—were originally from the village of Pordenau in Molotschna where

Helene and her husband Franz Bräul had married in 1921. The Derksens treated

Helene and daughter Käthe well; and when they sold the house to another

Mennonite family—Arthur Harders—the Derksens instructed Harders not to raise

the rent!

After one year in Canada Helene—with the assistance of extended

family and CMBC—was in a position to bring her son Walter and young family to

Canada. They arrived on May 12, 1956, and also boarded with their relatives in

Jordan Station (note 7). Walter worked all summer on the farm, and then a

relative of Walter’s wife Adina offered Walter construction work and rental

accommodations.

Helene also found new employment at the recently constructed

Mennonite Home for the Aged in Vineland next to their church, where many years

later she also lived as an older adult. Unfortunately, Helene’s job at the Home

required her to go in and out of a refrigerated room and her kidneys continued

to flare up. It was not long, however, before Helene was able to find work and

a rhythm that was suitable: labour in a greenhouse in the spring, on the fruit

farm in the summer, and at the Culver House Canning Factory near Vineland

Station in the fall.

Daughter Käthe was seventeen; she had completed high school

in Paraguay and had looked forward to teachers’ college there too. Now with a

change of language, culture, and academic approach, she felt her prospects of

becoming a teacher were bleak. But education had also been her father’s

explicit wish for the children, if at all possible. From a strictly financial

perspective, it made little sense. Helene however held to her commitment, and both

agreed for Käthe to attend English high school.

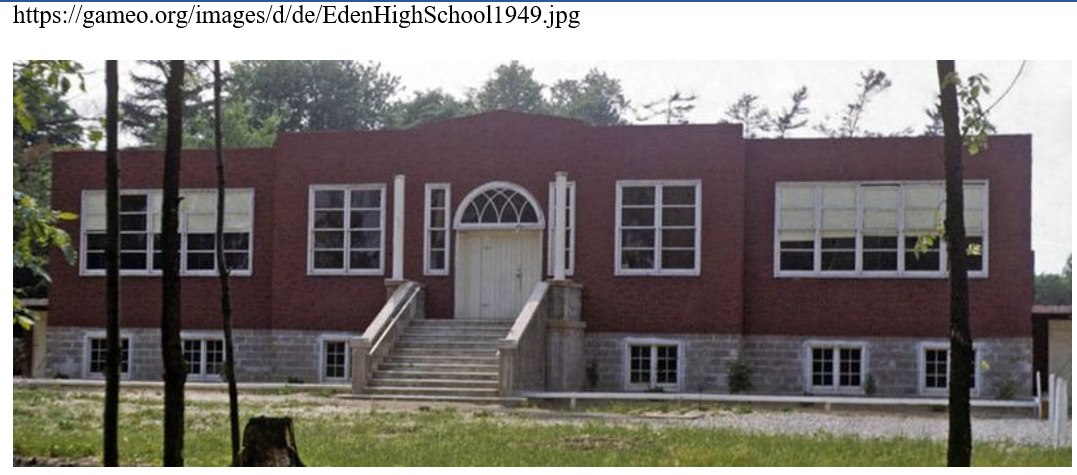

Eden Christian College, a publicly accountable, private

Mennonite Brethren high school in Virgil, Ontario about 35 kilometres from

Vineland was to become Käthe’s new Canadian home away from home. Eden was

established by another cousin of Helene’s—Henry B. Tiessen. Tiessen arrived in

Canada as a twenty-one-year-old in 1926. Its name too pointed back to a lost

paradise and promise of new beginning and blessing, surrounded by the orchards

of Niagara. Eden was established in 1945, with a new school building in 1947,

and an addition of four new classrooms and large gym-auditorium in 1955 for its

183 students (note 8), 66% of whom came from Mennonite Brethren congregations (note 9).

At Eden Käthe was placed directly into Grade 11 without knowing a word of English. The first year was particularly difficult, especially physics and chemistry, for in Paraguay their instruction had been without the luxury of any science equipment. The physics teacher—who also taught German—gave Käthe zero on her physics exam because her correct answers were in German! At Eden Käthe received room and board together with other students from Leamington, Toronto, Kitchener, and Port Rowan, and she reconnected here with a few old friends from Paraguay. She was encouraged on her first Canadian birthday when on November 19, 1955 the first snow of winter arrived—something she had not seen since leaving the Netherlands on the Volendam almost a decade earlier; she received it as a gift from heaven!

Towards the end of a difficult first school year in Canada,

Käthe thought she should leave school for a year and work to help her mother

financially and to learn more English. However, the principal at the time told

her not to quit on him. At the close of the year Käthe received “the most

improved student” award and a full tuition scholarship for Grade 12! Normally

this scholarship was designated for Mennonite Brethren students only, but many

years later Käthe learnt how one board member fought on her behalf—“because she

earned it.” The investment in this student paid off: she continued school and

by the end of Grade 12 she placed third overall.

If in Germany years earlier her sister Sara had been

encouraged to “Germanicize” her Jewish sounding name to Else upon

naturalization in 1944, now Käthe’s Canadian teacher encouraged her to

anglicize her name to “Katharine” for her diploma, suggesting that the

transition into post-war Canadian life would be more successful with an English

name. The next year she completed her Grade 13 program for students preparing

for post-secondary education at Vineland’s designated public high school in

Beamsville. She completed Teachers College afterwards as well and—after the

children had arrived—taught ESL for many years, but also German School in the

Vineland and St. Catharines area (note 10).

More than sixty percent of the 4,000 post-war Mennonite

refugees in Paraguay eventually immigrated to Canada. They were amongst some

8,000 Mennonite refugees in total from Europe to Canada between 1947 and 1958;

women outnumbered men approximately two to one (note 11).

Helene lived with daughter Katharine and her husband Peter

Fast in St. Catharines after they married in 1959. In the city she

found employment as an orderly at the Hotel Dieu hospital run by the Religious

Hospitallers of St. Joseph. The Hotel Dieu started as a maternity hospital; in

1962 the facility doubled its capacity to 250 beds in response to the growing

population (note 12). Helene used transit to and from work with a transfer

downtown where she could do her personal shopping. After a few years she had

earned and saved enough to purchase an investment property beside the church.

In the winter of 1965–1966, Helene, with

Katharine and family, travelled to Paraguay to visit her daughter Sarah, who with her

family had returned to Paraguay after a less than satisfying start in Canada.

After some thirty years as a widow and thirteen years in Canada,

Helene’s life took yet a very different turn when she was courted by a recently

widowed minister and elder in the St. Catharines United Mennonite Church, Peter

J. Heinrichs.

Heinrichs was born in 1889 in the village of Schardau, Molotschna, South Russia where Helene too was raised. In 1924 at the age of 35 Heinrichs and his first wife Maria Görz (1894-1963) immigrated to Canada and were among the original settlers in Springstein, Manitoba. Peter taught school for many years in the town of St. Elisabeth, and in 1952 he and his wife (they had no children) moved to St. Catharines where he became the congregation’s lead minister and last ordained elder.

My mother Katharine and her brother Walter were

understandably shocked by their mother’s new relationship; she had had so much

heartache over the years, and “old Reverend Heinrichs”—fourteen years her

senior—would need her care and likely not live many more years.

The couple married on March 23, 1968; Helene was 64 and

"Opa Heinrichs" as we called him was 78 years of age. I never had a

grandfather before, so this was all interesting for me. Helene transferred her

church membership from Vineland to the St. Catharines United Mennonite Church

at this time, and moved into his small house near the new and large church

complex in the north end of St. Catharines, completed in 1967.

They were a couple for four years and, though Helene played

the role of nurse for much of that time, she seemed much fulfilled to have a

husband and her own home and garden.

After his death, Helene lived another thirteen years at that

house—a five-minute walk from church and a convenience store—and was happy to

be known as “Frau Heinrichs.”

Her life in Canada rarely stretched beyond the rich circle

of church friends from the old country, and especially the other ladies from

her women’s group who had lived under both Stalin and Hitler, and made the

sojourn through Paraguay.

She had her Bible, her German devotional calendar, the

German-Canadian Mennonite paper (Der Bote), and the Gesangbuch der Mennoniten

hymnal. These were sufficient. Though Helene was not musical, she carried her Gesangbuch

every Sunday to church, and it included all the hymns that gave meaning and

sustenance to her and her generation—from a happy childhood and youth and

through all of the twists and turns and tragedies of her life. God’s hand,

God’s leading, were always quietly assumed, affirmed and celebrated.

Helene was not a broken person—at least not from the

perspective of her grandchildren who knew both her strength of character and

her love. It was important for Helene not to carry a grudge, to do what you

can, and to be grateful for what you have. God will take care of the rest. She

did not speak of the war, the Stalin years, or the revolution—let alone complain of what

life had brought her. She did not “go there,” likely because she could not. At her

bedside, there was always a handsome picture of her son Peter in German

uniform, conscripted into the German army at the tail end of World War II at

the age eighteen. This one picture was enough to indicate to her grandchildren

that she still carried some very deep pain, wounds she could not open, and with

many stories left untold.

In 1983 Helene suffered a series of small strokes from which

she never fully recovered. As her health declined she moved into the Vineland

Mennonite Home for the Aged where she spent her last years. Already in 1960 her

blood tests showed signs of Parkinson’s disease, and these symptoms became pronounced

in the 1980s. In 1985 Helene moved from her seniors’ apartment into a care

suite on the first floor of the Vineland Home. Helene passed away on Wednesday,

November 25, 1992, just days shy of her eighty-ninth birthday.

The events of Helene’s life connect at many points with the

evolution of Mennonite-Christian identity and ministry in Canada, especially

through the work of Mennonite Central Committee.

Hospitality and immigration assistance to refugees of war or disaster, together with famine relief, a special commitment to help the

family of faith, and inter-Mennonite cooperation became early themes that would

define and give direction for Mennonite ministry in the latter half of the

twentieth century.

---Notes---

Note 1: See previous posts, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/02/volendam-and-arrival-in-south-america.html;

AND https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/03/what-does-it-cost-to-settle-refugee-mcc.html,

etc.

Note 2: Cf. Valerie Knowles, Strangers at our Gates.

Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540–2006, revised ed. (Toronto:

Dundurn, 2007), 182; Esther Epp-Tiessen, J. J. Thiessen: A Leader for His Time

(Winnipeg, MB: Canadian Mennonite Bible College Publications, 2001), 182; J. J.

Thiessen, “Flüchtlingsansiedlung in Kanada: Die Einwanderung mennonitischer

Flüchtlinge nach Kanada seit 1947,” in Die Gemeinde Christi und ihr Auftrag.

Vorträge und Verhandlungen der Fünften Mennonitischen Weltkonferenz vom 10. bis

15. August 1952, St. Chrischona bei Basel, edited by H. S. Bender, 273–286

(Karlsruhe: Heinrich Schneider, 1953), 278f., https://archive.org/details/mwc-1952-fulltext.

Note 3: Ted D. Regehr, “Influence of World War II on

Mennonites in Canada,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 5 (1987), 73–89; 79, https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/141/141.

Note 4: Cf. e.g., “Beet labor for Alberta —Buchanan urges,” Lethbridge

Herald (February 13, 1947), 1, https://digitallibrary.uleth.ca/digital/collection/herald/id/197688/rec/3.

Note 5: Cf. G. N. Harder, “Fruit Growing in Vineland in the

Niagara Peninsula,” Mennonite Life 11, no. 2 (1956), 75–79, https://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1956apr.pdf;

also C. Alfred Friesen, Memoirs of the Virgil-Niagara Mennonites. History of

the Mennonite Settlement in Niagara-on-the-Lake Ontario, 1934–84 (Niagara-on-the-Lake,

ON, 1984).

Note 6: “Diary 1930–1971 of Elisabeth Klassen Reimer (1910–1994).” Copy in author’s possession.

Note 7: Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization Family Registration Form no. 9570, http://www.mennonitechurch.ca/programs/archives/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1947-60index.htm,

Note 8: See Henry B. Tiessen, Teaching in Ontario 1936–1970

(Kitchener, ON: Self-published, 1988); idem, The Molotschna Colony: A Heritage

Remembered (Kitchener, ON: Self-published, 1979).

Note 9: Friesen, Memoirs of the Virgil-Niagara Mennonites, 84. In 1954, twenty-nine percent were from United Mennonite Church background,

five percent others.

Note 10: See previous post (forthcoming).

Note 11: Cf. George K. Epp, “Mennonite Immigration to Canada

after World War II,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 5 (1987), 108–119; 116, https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/143.

Note 12: Cf. Great Beginnings: The First Fifty Years of

Caring at Hotel Dieu Hospital St. Catharines (St. Catharines, ON: Religious

Hospitallers of St. Joseph, 1998), 27.

Note 13: Esther Epp-Tiessen, Mennonite Central Committee in Canada: A History (Winnipeg, MB: Canadian Mennonite University Press, 2013), 34f.

Comments

Post a Comment