Thirty-five thousand Mennonites were evacuated from Ukraine for resettlement in German-annexed Poland in 1943/44. Almost all of them came through Litzmannstadt (Łódź)--one of only two points of processing and reception in the new German Province of Wartheland.

Here resettlers were thoroughly cleansed, disinfected, and

deloused in a large steam bath. Later arrivals from the long trek were mostly

full of lice, in their hair and up and down the seams of all their clothes, one resettler told me (note 1).

Besides lice, rickets and scabies were common, as well as

tuberculosis and trachoma. The larger concern however was racial purity and the

health of the Volk-body as a whole, consistent with the official “Racial

Policy” published by the Reichsführer S.S. Central Office for Racial Policy:

"Since the rise and fall of a people’s culture depends

above all on the maintenance, care, and purity of its valuable racial

inheritance, responsible statesmanship must be concerned with racial policy and

must do everything possible to maintain the purity of the racial inheritance

for the future. Our Führer, Adolf Hitler, was the first statesman in history to

recognize this and base his policies on it. The all-encompassing global war

that the German people are currently engaged in under his leadership is the

battle of the Nordic race against the forces of chaos and racial decay." (Note 2)

Albert Dahl told me that some of their Mennonite people

simply “disappeared” upon arrival in Warthegau—the handicapped and mentally weak.

My aunt Adina told me they were worried for her mother who was epileptic, that

she too might be "taken."

Today, many descendants use th Litzmannstadt “EWZ” forms of their grandparents for genealogical information. The EWZ, or Central Immigration Office (Einwandererzentralstelle) was comprised of representatives of Reich ministries for health and labour, Party officials, S.S. organs for political and criminal examination, and S.S. racial office experts (note 3). Early evacuees underwent discreet racial examinations based on anthropological evaluations of physical attributes (note 4).

The first Mennonite group to arrive in Litzmannstadt came

straight by train from Chortitza in October 1943; they were received with “unexpected

and touching warmth” and provided room and board in a former Jewish summer

resort. The Mennonite resettler Heinrich Hamm reported that “in every respect

we are taken care of.” Hamm was well versed in a twisted nazified history of

Russian Mennonite settlement, i.e., of “true Germans” who “opened up” the wide

expanses of the wild, wolf-populated eastern steppe without assistance from

Russian authorities. His letter to Danzig Mennonite Church board member and

kinship researcher Franz Harder contained racially-charged comments about those

of “mixed marriages.” But he and other “true Germans” from the Soviet Union

“thank God and the Führer daily with tears in their eyes for the great

privileges they may now enjoy.” Harder’s response to Hamm from Danzig was

signed with the German greeting, “Heil Hitler!” (note 5).

Harry Loewen was 14 years old when he was placed in a

residential all-boys school near Litzmannstadt.

"The songs we sang as we marched were meant to fan

German nationalism and hatred toward Germany’s “enemies,” especially the Jews.

I still remember some lines of these songs: … “Singing, we march into a new

Age. Adolf Hitler will lead us; we are ready to do battle.” A song that

vilified the Jews went as follows: “… Crooked Jews wander back and forth,

perhaps across the sea. The waves cover them and the world has peace.” (Note 6)

When the larger group of Mennonite refugees from

"Molotschna" had arrived in Litzmannstadt in March 1944, the city’s

Jewish ghetto was larger than the Warsaw Ghetto; the infamous Warsaw Ghetto

Uprising was only a month away.

Benjamin H. Unruh travelled freely with Pastor Abraham Braun

of Ibersheim—both born in Russia--throughout Warthegau and arrived in

Litzmannstadt on March 16 at the conclusion of a large two-day Nazi-party rally

in Litzmannstadt. Both had been in Germany for more than two decades.

Here Unruh consulted with the Reich Governor Arthur Greiser,

one of the architects of the Holocaust in Poland (note 7). Unruh was able to

reaffirm and secure for Mennonite resettlers the freedom to practice their

faith within the framework of the Nazi law (note 8). The Constitution of the

Alliance (Vereinigung) of Mennonite Congregations in the German Reich—first

drafted by Unruh in 1934—became the institutional identity into which Russian Mennonites

were to be received and provided pastoral care. It assured authorities that

German Mennonites had “renounced giving witness to their Christian peace

convictions through the particular principle of non-resistance” (note 9). Why?

Because in Nazi Germany the other historical distinctives for which Mennonites

had often suffered were “secure” and “had now become the common heritage of

all,” according to their Constitution. Mennonites now felt a stronger

“responsibility and duty towards Volk and state in which they lived.”

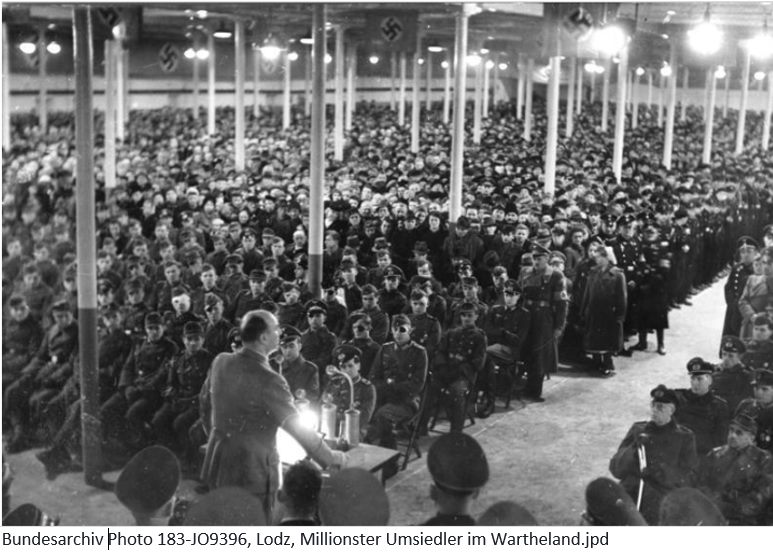

The two days before Unruh’s meeting with S.S. Gauleiter Greiser in Litzmannstadt, Greiser welcomed the “millionth resettler” to the Reich and addressed a large gathering of Volksdeutsche on March 14, 1944 (see photos). In an earlier telegram to Hitler, Greiser reported to the great satisfaction of the Führer that the Warthegau milestone had been reached, and added that “save for a tiny remnant, Jewry has completely disappeared, and Polishdom has been reduced from formerly 4.2 million to 3.5 million persons” (note 10). Though this fell far short of the demographic targets Hitler had set shortly after annexation in 1939, both he and Greiser were confident that the new era was now truly dawning.

Unruh agreed that Mennonite ministers in the camps would organize two worship services per month, and once a month resettlers and their ministers would participate in the Nazi Party Sunday “Morning Celebration” (Morgenfeier) (note 11). Its purpose was “to awaken and kindle for ever anew the forces of instinct, of emotion and of the soul which are vital for the struggle for existence and the bearing of our people and our race for all times” (note 12). Nazi Germany was not so much pro-church but spoke vaguely of "positive Christianity" in the party platform and of Germanic religion.

Greiser's vision was for “German lords” to rule over “Polish

servants." Greiser's Herrenvolk “took over the homes and farms of the Untermenschen,

literally lock, stock and barrel” (note 14). Some 65,000 Polish farms had been

forcibly evacuated by the end of 1942. Volksdeutsche resettlers in turn

received these farms.

Czesław Łuczak argues that that the “machinery of occupation set in motion to fight against any sign of Polish life would not have operated so efficiently had it not enjoyed the everyday help of the great majority of Germans inhabiting the Warta Land. … Their attitude towards the discriminatory actions of the authorities against Poles was completely passive” (note 15).

After disinfection in the border-city of Litzmannstadt, members of the Molotschna Mennonite evacuee group were put back on trains to proceed to the final destination and their new home in Warthegau.

“It seemed as if a long, long dream was coming to an end. We

were out of danger at last and in the Reich! In our exuberance we decorated our

freight cars with evergreen boughs and put up banners reading … “Home at last

in the Reich”! And yet some of us had lingering doubts and misgivings. … Were

we strangers from Russia, us refugees, really welcome?” (Note 16).

In this way, some 35,000 Mennonites from Ukraine entered the German Reich, prepared for full naturalization as German citizens in the next months.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Albert Dahl, interview with author, July 26, 2017. See related post on the delousing process, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/11/delousingnaked-in-litzmannstadt-odz.html.

Note 2: In Anson Rabinbach and Sander Gilman, eds., The

Third Reich Sourcebook (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013), 171.

Cf. Maria Fiebrandt, Auslese für die Siedlergesellschaft. Die Einbeziehung

Volksdeutscher in die NS-Erbgesundheitspolitik im Kontext der Umsiedlungen

1939–1945 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014), e.g., 537. See the similar

language used by German Mennonite leaders.

Note 3: Valdis O. Lumans, Hitler’s Auxiliaries: The

Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1933–1945

(Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 189.

Note 4: During the evacuation of 1944 there was less time

for extensive racial examinations. “Many of us remember Litzmannstadt. We were

X-rayed for tuberculosis purposes, but we cannot recall any blood work done

there. It was a simple and relatively quick process” (Johanna Dyck, Letter to

the editor, “Ukrainian survivors rebut ‘Aryan’ claims,” ‘Aryan’ claims,” Canadian

Mennonite 20, no. 22 [November 7, 2016], 9–10; 10).

Note 5: See Heinrich Hamm, Letter to Franz Harder, Danzig, October 6, 1943, in “Auswanderung aus Preussen nach Russland 1787–1854 (Auszüge aus Hypotheken),” Beilageakten des Staatsarchivs Danzig, https://chortitza.org/AuswPr.htm.

Note 6: Harry Loewen, Reflections of a Soviet-born Canadian

Mennonite (Kitchener, ON: Pandora, 2006), 70f.

Note 7: In Litzmannstadt from March 14 to 16, 1944, Greiser

hosted the first conference of the Regional and District Leaders of the Nazi

Party (NSDAP) Wartheland. In the addresses, the resettlement challenges were

addressed; cf. “Die Parole: Alles für den Sieg,” Litzmannstädter Zeitung 27,

no. 79 (March 19, 1944), 1. https://bc.wimbp.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication/31196/edition/29746/content.

See Benjamin Unruh's report: “Bericht über Verhandlungen in Warthegau im März

1944” (March 30, 1944), 6b, Benjamin Unruh Collection, File Folder:

Correspondence with Abraham Braun Correspondence, Mennonitische

Forschungsstelle Weierhof.

Note 8: Karl Götz, Das Schwarzmeerdeutschtum: Die

Mennoniten (Posen: NS-Druck Wartheland, 1944), 11, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/books/1944,%20Goetz,%20Die%20Mennoniten/1944,%20Goetz,%20Die%20Mennoniten.pdf.

Note 9: Vereinigung der deutschen Mennonitengemeinden, Verfassung

vom 11. Juni 1934 (Elbing: Kühn, 1936), 4, 5.

Note 10: In Catherine Epstein, Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser

and the Occupation of Western Poland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010),

191, https://books.google.ca/books?id=Caa4rl8SHHwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=. At this point, about twenty-three percent of Warthegau’s population was German

(ibid., 192). Cf. “Der millionste Deutsche im Wartheland angesiedelt,” Litzmannstädter

Zeitung 27, no. 75 (March 15, 1944) 1. https://bc.wimbp.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication/31192/edition/29742/content.

Note 11: Cited in Aryeh L. Unger, The Totalitarian Party:

Party and People in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1974) 174.

Note 12: Cf. Karl Götz, Das Schwarzmeerdeutschtum: Die

Mennoniten (Posen: NS-Druck Wartheland, 1944), https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/books/1944,%20Goetz,%20Die%20Mennoniten/1944,%20Goetz,%20Die%20Mennoniten.pdf.

Note 13: Valdis O. Lumans, “Reassessment of Volksdeutsche

and Jews in the Volhynia-Galicia Narew Resettlement,” in The Impact of Nazism:

New Perspectives on the Third Reich and Its Legacy, edited by Alan E. Steinweis

and Daniel E. Rogers, 81–100 (Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 95.

Note 14: Czesław Łuczak, “Chronicle: Records on the

Situation of Poles in the Warte Land,” Instytut Zachodni (Poznań), Western

Affairs 8, no. 1 (1967), 168–190; 170.

Note 15: Katie Friesen, Into the Unknown, (Steinbach, MB: Self-published, 1986), 73.

Comments

Post a Comment