Usually it is better for me to say nothing on Remembrance Day ( =Armistice Day or Veterans Day), November 11.

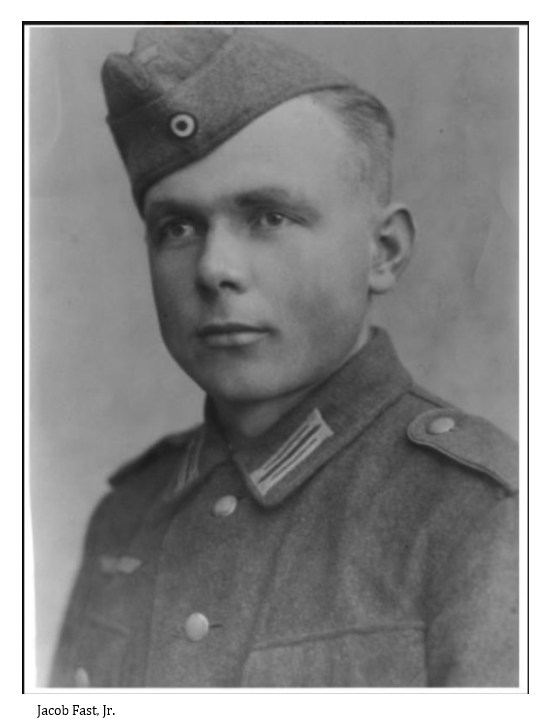

I have five uncles who fought in German uniform: Dad’s

brother Jacob Fast returned to Germany from Friesland, Paraguay and died on the

eastern front in 1944, age 25 (note 1).

Mom’s brother Peter Bräul died from wounds in Linz, Austria, 1945, age nineteen.

In the same weeks their brother Heinrich was killed in battle in Budapest, around his twenty-first birthday.

Another brother, Franz, was captured in Budapest and died a few years later from starvation in a gulag in Russia’s far north.

Their youngest brother Walter was captured by the British in Denmark at the end of the war—he had just turned 17 (note 2).

Their 8-year-old sister Helene (Lenchen) died on the 1943 “trek” while being evacuated behind German army lines—another victim of the war (note 3).

My mother Käthe was the youngest; her sister Sara and my grandmother had fled as far as north-western Germany by war’s end. They and other Molotschna / Gnadenfeld district refugees had escaped advancing Soviet troops in Warthegau (annexed Poland) and were designated for the Municipality of Hermannsburg, District of Celle in Lower Saxony, about 300 kilometres west of Berlin.

Helene Bräul (my grandmother), my mother and Sara were sent

to a Hilmer family in the village of Bonstorf; population 280 (1939). Because

of the numbers of refugees from the east, but also from cities like Hamburg,

the numbers of children in the village school more than doubled pre-war

enrollments, from 62 in 1939 to 143 in 1945 (note 4).

Polish and French POWs were also part of the village mix as agricultural labourers (note 5).

During this time everyone listened eagerly to radio reports

to learn how the war was going and to get advance warning of “enemy” air

squadrons. Sixty-six villagers had been conscripted, and one-third would never

return (note 6).

As it became clear that Germany would soon be defeated, the Führer

delivered a chilling eleventh-hour appeal over wireless radio calling “for all

Germans, including young teenagers, to offer every possible form of guerrilla

resistance to the enemy in occupied parts of Germany (note 7).

“Very young” Hungarian axis (child-) soldiers with no battle

experience were evacuated to the Bonstorf and region for military training.

“All day long we could hear the explosion of hand-grenades and bazookas, as

well the infantry's machine-gun fire from drilling grounds,” locals recalled (note

8).

On Sunday morning, April 15, 1945—two weeks after Easter—the

young Hungarian soldiers marched through the village singing confidently yet

unaware that allied tanks were fast approaching. In the afternoon mom and other

children were playing on the street around the Memorial for Fallen Soldiers (see

pic), when one girl heard what sounded like deep thunder—though it was a sunny

day. Suddenly sister Sara came running from the house shouting to the children,

“The front is approaching!,” and that everyone should run home. Allied tanks

shot in the direction of the young Hungarian soldiers, who were commanded to

defend the village on its southern edge, and then into the village where they

detected resistance as the young Hungarians fled.

American troops soon entered the small village of Bonstorf

and went house to house, setting several homes in fire. The Hilmer barn,

located on their yard (Hof) across from their house, was being used by the

German military as a depot for food supplies and was guarded by two soldiers.

The American intelligence knew this and set the barn on fire, flushing out the

two soldiers. As the soldiers fled the barn, they were shot at from the house

across the street and very badly wounded. Hans Hilmer ran out and pulled the

two soldiers into his house. Mom, only seven years old, witnessed everything

from the window. Hilmer then instructed everyone into the potato cellar through

the trap door in the kitchen for safety. Villagers were required to have enough

air raid shelter space for all, and residents had practiced their use,

including gas masks and first aid for years (note 9). They were all huddled in

close quarters; it was very traumatic for my mother to see the soldiers

groaning and wrenching in pain, and everyone very afraid of what would happen

next.

The American soldiers entered and upon finding the root

cellar door they opened it and ordered everyone out by gunpoint. They took the

German soldiers and then proceeded to search the entire house. Everyone was

very frightened. The Hilmer and Bräul families were then ordered back into the

cellar—but only after they told the Americans where the family’s food supplies

were. While huddled in the basement, the soldiers helped themselves to food and

cooked a large meal in the kitchen and spent the night.

Bonstorf was now under Allied occupation and would become

part of the British occupation zone for years to come.

On this same weekend Allied troops overran and took control

of the entire region around Bonstorf. The village was only twenty kilometres

from the notorious S.S.-run Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, where, only one

month before the camp’s liberation, the well-known fifteen-year-old Jewish

diarist Anne Frank died of typhus (note 10). The accounts of what Allied

soldiers found when they liberated the camp on April 15, 1945 are horrific

My mother remembers overhearing shocking descriptions given

by the Hilmer girls, who were forced by the British to clean some of the buses

in which enslaved and horribly abused Jews and other eastern Europeans had been

transferred.

In this way the war ended for this group of Gnadenfeld

refugees.

All of this happened 77-plus years ago. So much death, and

our family members were on the “wrong side” of the war too.

How does a Mennonite, and a Mennonite with this background

“do” Remembrance Day? I never know.

However, I resist the temptation to glorify the death and

heroism of warriors—family members or not, Canadian or German. War is always

tragic and there is nothing to celebrate. But it is surely important to

remember these family members, and to grieve their loss, to grieve war, and all

those who suffer and have suffered because of war.

The Mennonite Central Committee button helps me to interpret

the “poppy” and my own family history: “To remember is to work for peace!”

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: See my post on Jacob Fast, Jr., https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2022/09/in-january-2020-i-received-information.html.

Note 2: See my posts on Peter Bräul (forthcoming); on

Heinrich (and Franz) Bräul, (forthcoming); and on Walter Bräul see previous

post (forthcoming)

Note 3: See previous post on Lenchen Bräul (forthcoming)

Note 4: Giesela Meyer, “Bonstorf: Unser Dorf im Krieg und in

der Nachkriegszeit,” December 15, 1952, 4b. In folder 295, no. 1, Archiv

Landkreis Celle, Germany.

Note 5: Meyer, “Bonstorf: Unser Dorf im Krieg,” 1b.

Note 6: Meyer, “Bonstorf: Unser Dorf im Krieg,” 2a, 2b.

Note 7: Waldemar Janzen, Growing up in Turbulent Times (Winnipeg,

MB: CMU Press, 2007) 84.

Note 8: Meyer, “Bonstorf: Unser Dorf im Krieg,” 4b.

Note 9: Cf. Meyer, “Bonstorf: Unser Dorf im Krieg,” 3, 5.

Note 10: Anne Frank was taken from her attic hideout in

Amsterdam by the Nazis in August 1944, and became known around the world when

her diaries were published after the war.

Comments

Post a Comment