With the illegal invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, Ukrainian

women and men were/are being hailed for their "partisan" fighting

against Russian aggression. A similar level of partisan fighting was displayed

during Nazi occupation of Ukraine, Fall 1941 to Fall 1943.

There is at least one archival account of a young Mennonite

woman who became an active underground supporter of a partisan group on behalf

of Ukraine/ USSR during German occupation: Anna Petrovna Wiens.

The Mennonite story in Ukraine during WWII is messy. Some

35,000 Mennonites welcomed and embraced the Germans as liberators from the very

real repression and terror they experienced under Stalin.

Anna Wiens however was different—she became a partisan fighter against the Nazis. Anna was born in 1918 in Kleefeld, Molotschna to Peter and Elisabeth (Klassen) Wiens, and she had Mennonite cousins who immigrated to Canada mid-1920s. But according to a later testimony by her Ukrainian husband and director of the village school, Vladimir Okunta, “there was nothing German in her. … She considered fascist Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union 'a treacherous attack on her homeland,' ... and she considered Nazi warriors to be barbarians and criminals." As “true patriots of their homeland,” they could not resign themselves to submit themselves to a regime that considered itself to be a “master” race (note 1).

In 1941 when the Germans arrived, Anna lived and worked with her husband in the village of Alexandrovka just outside of the German settlement.

Anna registered with the occupying force as an “ethnic

German” and received all the benefits and protections of a German: better food

and clothing and other rights not afforded to Ukrainians, Russians or Jews.

There is no indication that Anna had any connection to her family's Mennonite

faith background as an adult.

With her husband she became a supporter of a Ukrainian

partisan group, whose task was to extract ammunition, to organize acts of

sabotage in public agriculture, to share information with the underground, and

to frustrate the movement of agricultural products to the German army.

Because she was of German-Mennonite descent and spoke

perfect German, officers and officials treated them "with great

confidence," and sometimes went to her home to "drink tea" or

"to shave."

With privileged information, Anna and her husband apparently

foiled a German plan to send a large catchment of local Ukrainian youth to

labour camps in Germany. Any youth resisting would be shot, but Wiens provided

false health records with illnesses that were incompatible with residency in

the German Reich. Other young people were warned about their planned departure

and fled from the village. And Wiens hid some in her home as well, according to

her husband.

With the fall of Stalingrad, Germany's military fortunes in

Ukraine turned. Memoirs from Mennonites in the same area record that

"partisans" became increasingly bold. From the nearby Mennonite

village of Marienthal (Molotschna), one Mennonite recalls:

"In August while Elsie and some of the other girls were

working the fields behind our village near a hedge, they thought there were

Partjisane (partisans, or guerilla snipers) shooting at them. … The next day

when they went out again, they found empty ammunition shells and returned to

the work yard, refusing to work in the fields again. Then the refugees going

west began to travel through our villages again. They reported that the Germans

were suffering terrible losses, and that their own villages were burnt." (Note

2)

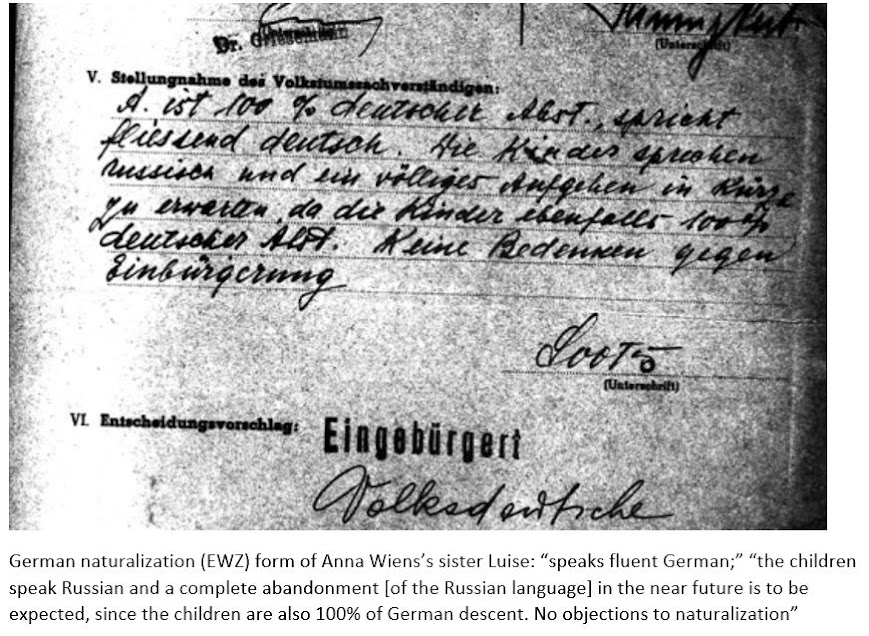

Anna Wiens did not retreat behind German lines together with 35,000 other Mennonites in September 1943, though her mother and sister Luise Unrau did (note 3). Luise's German naturalization papers (EWZ) indicate that she and her children were deemed “100%” German, though the children’s German language skills were weak. Luise like her sister Anna was born in the Molotschna village of Kleefeld, but she also lived in Donbas, Melitopol and Tokmak (the latter two near Molotschna). Though her reported genealogy has the names Warkentin, Toews, Klassen and Wiens, Luise registered for German naturalization as “Lutheran;” curiously she also refrains from swearing an oath—a Mennonite privilege in Nazi Germany.

As noted Luise's sister Anna did not retreat with the

Germans. Nevertheless, at the end of the war Anna was tried by a Soviet

tribunal with treason for accepting ethnic-German identity papers during

occupation. Anna Wiens was sentenced to five years of forced labour in

Kazakhstan.

Ukrainian archivists have produced an entire essay on Anna Wiens and her resistance during German occupation. It appears in a large series of volumes cataloging the tens of thousands of arrests and executions during the Stalin era (see note 1).

About 500 to 700 Mennonite men (generally younger than Anna), all without any memory of church, were trained by the German occupying forces as an elite military cavalry unit with the primary task of fighting "partisans" in the immediate area of these German villages (note 4).These are all part of the messy, deadly web of war in which

Mennonites in Ukraine were caught—between Stalin and Hitler.

Today's Ukrainian "partisans" (language used by

CNN) remind me of the story of Anna Wiens.

I still do not know how to properly frame her unique

defiance and courage to stand up against the Nazis and fight on behalf of the

Ukraine underground—but also against her Mennonite people.

There are no other Mennonite stories of active resistance against Nazi Germany in Ukraine that I am aware of though at least two attempts to poison officials (June 28, 1943) or cavalry members in Halbstadt were attempted (note 5).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Rehabilitated History: Zaporizhia Region, Book III

(Zaporizhia: Dniprovskij Metalurg, 2006) 210-215. [РЕАБІЛІТОВАНІ ІСТОРІЄЮ:

Запорізька область]. http://www.reabit.org.ua/files/store/Zaporozh-3.pdf.

Also available on pp. 140-144 of: https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/Pis/Sapor.pdf.

For biographical information on Anna Petrovna Wiens, see GRanDMA #1070782.

Note 2: Selma Kornelsen Hooge and Anna Goossen Kornelsen, Life

Before Canada (Abbotsford, BC: Self-published, 2018), 59.

Note 3: Cf. "Elisabeth Klassen," born 1879 in

Ladekop, in Richard D. Thiessen, "Index of Mennonites Appearing in the

Einwandererzentrallestelle (EWZ) Files," film A3342-EWZ50-I069, frame 206.

https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/EWZ_Mennonite_Extractions_Alphabetized.pdf.

Note 4: See previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/08/notes-on-lost-generation-first-ethnic.html.

Note 4: See previous post (forthcoming, including sources from Roßner, Eduard Reimer and Bundesarchiv VoMi correspondence).

---

To cite this post: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "Terrorist or

Freedom Fighter? The "partisan" Anna P. Wiens," History of the Russian

Mennonites (blog), June 11, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/06/terrorist-or-freedom-fighter-partisan.html.

Comments

Post a Comment