"Their accomplishments are unprecedented globally with houses cleaner than the Dutch!" 1843 description

As long as Johann Cornies was living (d. 1848), Mennonites

in Russia received many distinguished visits and reports appeared in any variety

of Imperial journals (note 1). The following report was written by a British

visitor in 1843 and appeared in a journal of international “commercial

treaties, customs tariffs, port laws, etc.” (note 2).

The report makes reference to the newly established port

city of Berdjansk, which was key to the wheat revolution in New Russia and the

fantastic wealth of some like Johann Cornies (note 3).

The British editor warns that the description may be

exaggerated, e.g., the statement on Cornies’ wealth—but likely the latter is

accurate. For his British readers the writer converts Cornies’ net worth to

100,000 Pounds Sterling—what a 1,000 clerks in London might make together in a

year (note 4).

While the account is not altogether unique or important for understanding

Russian Mennonites, parts that stand out in the description include comments on

industry, wealth and the extreme cleanliness of Mennonite homes, “which cannot

be surpassed even by the Dutch.”

The writer assessment brings a British colonial mindset typical

of the era when contrasting the German-speaking settlers to the indigenous

Nogai: “The vast territory […] was formerly occupied by hordes of roving

Nogayz. Those barbarians were compelled by the Russian government to fix

themselves in villages, and to abandon their vagabond life, and addict

themselves to labour. They have built houses after the model of the German

colonists, and have learned from them different branches of industry.”

Here is the full text.

"… The following is an account of these colonists

written during the early part of 1843, at Taganrog. It is very interesting, but

we take it as we do nearly every statement drawn up in Russia, as being, to say

the least, somewhat exaggerated:

'The progress which cultivation has made in Southern Russia

is extraordinary. With the exception of North America there is not perhaps a

country in the world where the efforts of an active and industrious population

have produced such brilliant results in so short a space of time.

It is not yet fifty years since the German Mennonists,

having been compelled to expatriate themselves from Prussia, on account of

their having been subjected to military service, arrived in Southern Russia.

The Emperor Paul granted them valuable privileges, which

were confirmed by his successors. A vast territory was distributed amongst

those colonists (who were quickly followed by a crowd of other families from

Wurtemberg, Baden, and Switzerland), on the left bank of the Moloschna, a small

river which traverses the steppes to the north of the Sea of Azof.

Each family of Mennonists received sixty-five measures of

good arable land, and several other advantages were granted them.

The Mennonists in Russia are exempt from military service,

and appoint their own judges. They are even permitted to distil brandy for

their own use, which is considered an immense favour in Russia, where the

monopoly of the fabrication of spirituous liquors produces an enormous revenue

to the crown.

The arrival of the members of this sect, who each brought a

handsome fortune in ready money, was an excellent acquisition for an

uncultivated though fertile country, which only required active arms to

metamorphose it in a short time into a vast garden.

It comprises at present about fifty villages upon the left

bank of the Moloschna, which are in a most flourishing condition. Nothing is

more agreeable for a traveller who has traversed the immense and monotonous

steppes inhabited by Nogayz Tartars than the appearance of those charming

Mennonist villages, whose white houses covered with tiles are surrounded with

gardens planted with fruit trees, and acacia-trees, not to be seen amongst the

steppes.

When one enters the dwellings of the Mennonists, it is easy

to perceive that they live comfortably. Extremely simple in their dress, the

Mennonists display a certain degree of luxury in the interior of their houses

which is nowhere to be found in the Russian villages. The cleanliness of their

habitations is extreme, and cannot be surpassed even by the Dutch.

I am acquainted with a Mennonist named John Corneis [sic],

who resides in the village of Orloff, and whose private fortune may be

estimated without exaggeration at more than 2,000,000 roubles of assignation

(about 100,000/. sterling).

It was at his house that the Emperor Alexander lodged when

he visited those countries, and where he was superbly feasted. John Corneis,

who, though very devout, is considered as extremely sharp in money matters,

took the opportunity of the emperor’s visit to obtain many advantages.

The German colonists on the right bank of the Moloschna, who

are almost all Lutherans, have not been so highly favoured as the Mennonists.

Having arrived without any capital, and possessing no resource but that

generously afforded them by the Emperor Alexander, their present condition

cannot be compared to that of the Mennonists.

They live comfortably, however, and contribute much by their

activity to the rapid colonization of the vast territory which was formerly

occupied by hordes of roving Nogayz. Those barbarians were compelled by the

Russian government to fix themselves in villages, and to abandon their vagabond

life, and addict themselves to labour. They have built houses after the model

of the German colonists, and have learned from them different branches of

industry.

The cultivation of wheat is the most profitable branch of

agriculture in the steppes- The annual amount of wheat exported from the ports

of the Sea of Azof is estimated at 300,000 chetwerts (9,600,000 lbs.), and if

the colonization of the steppes proceeds with an equal rapidity, a double

quantity may be exported in ten years hence.

The new port on the Sea of Azof, called Perdjausk

[Berdjansk], which has existed but six years, is already a handsome town, and

contains 2500 inhabitants: its situation, in the neighbourhood of the colonies

on the Moloschna, is so favourable that it may soon rival Taganrog. The

population is composed of Greeks, Italians, and Russians, who have established

themselves there to deal in corn.

The port of Perdjausk [Berdjansk] is much better than that of Taganrog, where ships cannot anchor nearer than at a distance of six versts. Merino wool is, after wheat, the next most important article of produce in the steppes. This article, however, begins to diminish, as the price of wool has fallen considerably since the year 1831. At that period fine wool sold for 60 roubles assignation (2/. 10s. sterling) the pois (a weight of 40 Russian pounds). At present the price has fallen to 1/. 5s, British for the same weight. The Mennonists, who possess immense flocks of sheep, now sell their wool at an inferior price. Many fortunes in Southern Russia have considerably suffered by the fall in the price of wool, which has been experienced during the last four years.”

---Comments by Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: See the dismal 1843 description of Mennonite

communities in Russia by a representative of the London Bible Society and

published by a Boston-based Baptist newspaper: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/02/1843-london-bible-society-revival-and.html.

Note 2: John Macgregor, A Digest of the Productive

Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs, Navigation, Port, and

Quarantine Laws, and Charges, Shipping, Imports and Exports, and the Monies,

Weights, and Measures of all Nation. Including all British Commercial Treaties

with Foreign States (London: Christopher Knight, 1844), vol. 2, 726-728,

https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Commercial_statistics/-gZAAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA726&printsec=frontcover.

Note 3: See previous post (forthcoming).

Note 4: Literature around Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol”

(1843) estimates that the salary of a junior clerk like “Bob Cratchit” with one

to five years’ experiences in a small firm like Ebeneezer Scrooge’s in London

would be about 100 pounds a year give or take. No guarantees! See calculation

by James Hoover, https://www.quora.com/Scrooge-paid-Bob-Crachit-15-bob-a-week-How-much-was-that-in-1850-How-much-would-it-be-today

.

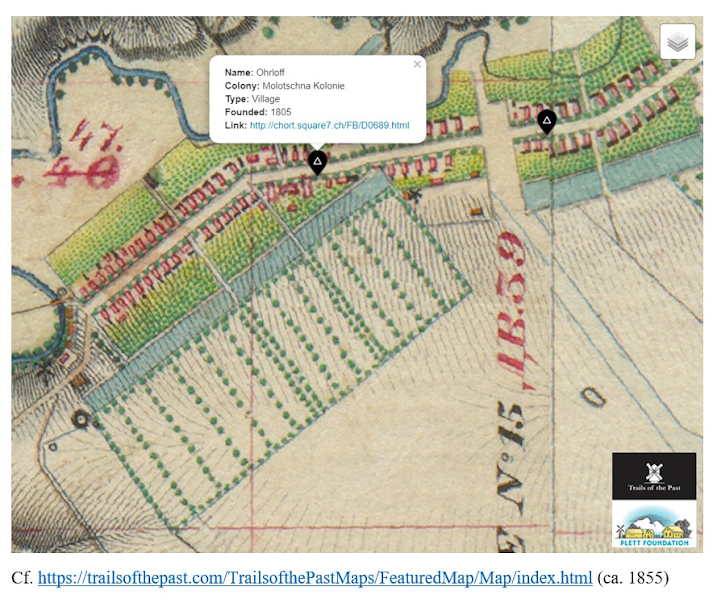

Village map/ pic of Ohrloff (1855) courtesy of Brent Wiebe:

https://trailsofthepast.com/TrailsofthePastMaps/FeaturedMap/Map/index.html.

The image of a youthful Johann Cornies was likely drawn by his appointed Agricultural Society instructor, Heinrich Heese.

Comments

Post a Comment