Photographs of German troops in southern Ukraine, 1918, have recently come to light. These offer a new window on Mennonite life during the short period of "friendly" German occupation. A number of these photographs are attached to this post and complement previous posts on this period (note 1).

On February 17,

1918, Ukraine appealed to Germany and Austria-Hungary for assistance to repel

“Bolshevik invaders,” to detach Ukraine from Russia, and to establish

conditions of stability (note 2).

Anticipating the

imminent arrival of German troops early in 1918, some Mennonites had already

taken up arms in self-defense against the anarchist leader Nestor Makhnov; the

“thunder” of the cannons in the vicinity gave strong indication that the German

army was near (note 3).

Some 450,000

occupying German and Austrian troops changed the equation for the Bolsheviks

and anarchists in Ukraine. Some German Mennonites were among those soldiers,

including the brother-in-law to teacher and community leader Benjamin H. Unruh.

In his diary, Jacob P. Janzen in Rudnerweide wrote:

May 21, 1918: “A high ranking general was to be here for

“klein” [small] breakfast, but only came for lunch. He is a Prussian, currently

from Melitopol, and is the Chairman and Adjutant. … On our street an honour

display had been set up, decorated with flowers and grass. After breakfasting

he shook hands with all the Rudnerweide people, asking them whether they were

local people and if their name was of German origin. He also spoke to the

children and when he left the children threw flowers into his car. He waved to

all and on the street … gentlemen took off their hats and waved with them.” (Note 4)

Also in May a decree by the occupation forces made courses

in the “art of war” obligatory for Mennonite school children up to age twelve,

as well as for older youth to age eighteen. Men eighteen to forty were to be

conscripted for eight weeks of training for a minimum of twelve hours per week;

women could join as well, but were not obligated (note 5).

But this step was not as obvious as the Germans had expected.

Because the use of arms for organized self-defence was something novel in the

tradition, the General Mennonite Conference of Churches organized four days of

meetings in Lichtenau on “the confession of non-resistance among Mennonites”

and “political questions” (note 6). The church was required to respond by July

4 on the establishment of self-defence militia units.

Informed debate was however difficult; the German occupying

force heavily censored the Mennonite press from publishing articles supporting

non-resistance (note 7). The Deutsche Zeitung für Ost-Taurien, published by

the German army administration at Melitopol, printed a column that challenged

the “inner justification” of biblical pacifism in response to the Mennonite

congress in Lichtenau, and framed the division in the community generationally:

“While the younger, progressively-minded portion of congregations declared

their willingness to accept universal conscription, the older ones were against

it.” The columnist—likely an army chaplain—closed his biblical argument with a

reminder: “When the Bolshevist reign was broken, who was here in Melitopol

first to request [German] military protection and weapons for self-defence?—The

Mennonites!” (note 8). German army leadership around Melitopol and estate

owners were dependent upon each other (note 9).

Janzen’s diary gives us a snapshot of how this was experienced on the ground.

"August 1918: Two of the Germans began a military drill

in our forest with our volunteers for the Selbstschutz, 20 young men from our

village and 10 from Großweide. Four days later we received a notice that all

men from 18 to 45 years old were to appear at a general meeting with the

village mayor. The German was there too and read an order out of a little

notebook, telling us to join the Selbstschutz, all men age 18 to 25. If there

were not enough of these he would conscript older men too. The order was signed

only by initials of some unknown person. And he expected us to accept! Did he

really think us that stupid? Brother David [a minister] and I and many others

spoke strongly against it." (Note 10)

As late as mid-September, the official German press written

for both soldiers and settlers found it necessary to explain the rationale for

a Selbstschutz to reluctant communities, offer examples of success, and entice

“eager, cheerful” young men for a training with purpose, that promised not to

be “uninteresting.”

“The occupation of every village and of every larger estate

[with troops] in all of Taurien is obviously impossible. In order to give

residents the possibility to defend their property and possessions from those

uncertain and indolent elements, the German military authority has commanded

the creation of a Selbstschutz in every village community. They are not to replace

the military force, but to support them where a late arrival of military forces

can be expected.” (Note 11)

In 1918 in the Region of Taurien (including Crimea), there

were 56,000 German Lutherans, 27,000 German Catholics, 50,000 Mennonites and a smaller

community of German Baptists (note 12). The new sense of German ethnic

brotherhood and incautious enthusiasm for the Reich would come back to haunt

the German settlements later that year—and for decades to come.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

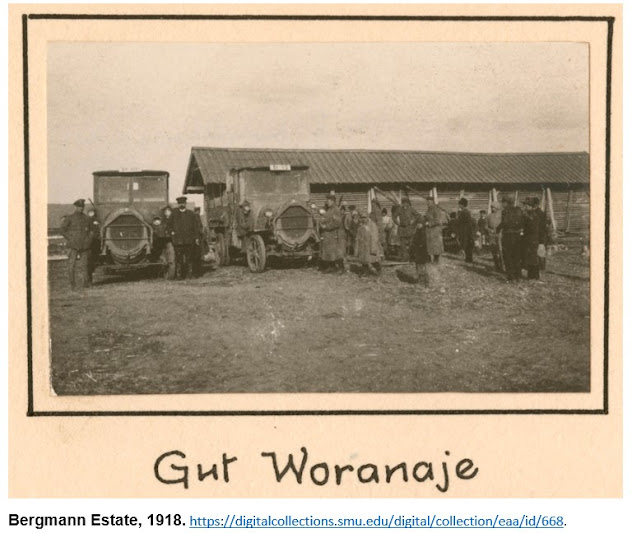

Note 1: I thank Dr. James Urry for sharing a link to a portfolio

containing 263 photographs documenting the advance of the German Flight

Squadron 27 in the Ukraine during Spring and Summer of 1918, from Southern

Methodist University, Texas, https://digitalcollections.smu.edu/digital/collection/eaa/id/668. See previous posts: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/april-19-1918-mennonites-in-ukraine.html and https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/becoming-german-ludendorff-festivals-in.html.

Note 2: Cf. Oberste Heeresleitung, “Denkschrift: Über die

Wahrung der Interessen des Reiches in den neuen Ost-Staaten in strategischer,

wirtschaftlicher und verkehrspolitischer Hinsicht durch Konzessionsierung einer

Osteuropäischen Verkehr-Gesellschaft (June 1918),” Reichskanzlei Kriegsakten

4:2, vol. 3 (März–Juli 1918), 185–188 (BArchR 43/2406). From Bundesarchiv

Berlin-Lichterfelde, https://invenio.bundesarchiv.de/; also Vzfw. (Sergeant)

Rießner, “Das Ziel des deutschen Einmarsches in die Ukraine,” Deutsche Zeitung

für Ost-Taurien [DZOT] 1, no. 40 (July 25, 1918), 2f.,

https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/suche?queryString=PPN777397188. See

esp. Wolfram Dornik, et al., The Emergence of Ukraine: Self-Determination,

Occupation, and War in Ukraine, 1917–1922, translated by Gus Fagan (Edmonton:

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2015).

Note 3: “H.U.” [Halbstadt Elder H. Unruh] wrote May 18, just shortly after German occupation, that “after having taken up arms for our own self-defence, we will likely be required to do the same for the protection of the Fatherland” (Volksfreund II/XI, no. 20 /38 [May 18, 1918], 2), https://chortitza.org/pdf/pletk25.pdf. Another writer also refers to the use of weapons by Mennonites prior to German occupation “to protect our earthly goods” (Volksfreund II, no. 15 [April 23, 1918], 1; link broken). Cf. Gerhard Schroeder, Miracles of Grace and Judgement: A Family Strives for Survival During the Russian Revolution (Lodi, CA: Self-published, 1974), 28f.

Note 4: Jacob P. Janzen, “Diary 1911–1919. English monthly

summaries," edited and translated by Katharina Wall Janzen. From Mennonite

Heritage Centre, Winnipeg, MB, Jacob P. Janzen fonds, 1911–1946, vol. 2341.

Note 5: Notice in Volksfreund II, no. 20 (May 18, 1918), 6,

https://chortitza.org/pdf/pletk25.pdf. The arming and military organization of

colonists into local Selbstschutz units was directed by Berlin, as was the

support for a strong crop for export (cf. Jochen Oltmer, Migration und Politik

in der Weimarer Republik [Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005], 177f.).

Note 6: Friedensstimme 16, no. 36 (July 23, 1918), 1,

https://chortitza.org/pdf/pletk47.pdf. Old “mission-friends” felt that

reporting on the real “work of the kingdom of God,” namely the mission work in

Sumatra and Java, was squeezed out.

Note 7: For example, Jakob Wiebe’s paper in support of

non-resistance presented at the Lichtenau General Conference of the Mennonite

Congregations in Russia, June 30 to July 2, 1918, was only published a year

later (cf. “Zur Wehrlosigkeit der Mennoniten,” Friedensstimme 17, no. 27

[August 10, 1919]: 2f., https://chortitza.org/pdf/pletk51.pdf). The editor, who

was completely exasperated by his German army censor, noted apologetically that

the article would have been impossible to publish under occupation, and was held

back.

Note 8: “Die Mennoniten und die allgemeine Wehrpflicht,” DZOT

1, no. 27 (July 10, 1918), 2,

https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/suche?queryString=PPN777397188.

Note 9: Cf. “Biography of Jacob Cornelius Toews,

1882–1968,” translated by Frieda Toews Baergen (Essex-Kent Mennonite Historical

Association Leamington), 27f., https://www.ekmha.ca/collections/items/show/42.

Note 10: J. Janzen, “Diary 1916–1919.”

Note 11: “Selbstschutz,” DZOT no. 87 (September 18, 1918):

2, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/suche?queryString=PPN777397188.

Note 12: Cf. A. Bühler, “Das Deutschtum in Taurien,” Deutschtum

im Ausland, no. 36 (1918), 358-362,

https://books.google.ca/books?id=4wo2IhXfUskC.

----

The following photographs are from a portfolio containing 263 photographs documenting the advance of the German Flight Squadron 27 in the Ukraine during Spring and Summer of 1918, from the Digital Collections of Southern Methodist University (SMU), Texas, https://digitalcollections.smu.edu/digital/collection/eaa/id/668.

Comments

Post a Comment