Johann Cornies expanded his Agricultural Society School library in Ohrloff to become a lending library “for the instruction and better enlightenment of every adult resident.” The library was overseen by the Agricultural Society; in 1845, patrons across the colony paid 1 ruble annually to access its growing collection of 355 volumes (see note 1).

The great majority of the volumes were in German, but the

library included Russian and some French volumes, with a large selection of

handbooks and periodicals on agronomy and agriculture—even a medical handbook (note 2).

The great majority of the volumes were in German, but the

library included Russian and some French volumes, with a large selection of

handbooks and periodicals on agronomy and agriculture—even a medical handbook (note 2).

Philosophical texts included a German translation of George

Combe’s The Constitution of Man (note 3) and its controversial theory of

phrenology, and the political economist Johann H. G. Justi’s Ergetzungen der

vernünftigen Seele—which give example of the high level of reading and

reflection amongst some colonists.

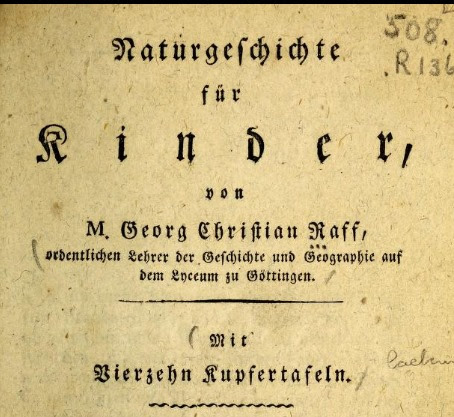

The library’s teaching and reference resources included a

history of science and technology with an accompanying volume for students by

Carl P. Funke; natural science text for children (note 4); an elementary school

Russian reader for German pupils; Russian-German, Turkish-German (note 5), and

Latin-German dictionaries; encyclopedia; many songbooks; pedagogical journals;

the St. Petersburgische Zeitung (conservative Baltic-Russian German newspaper);

a Prussian newspaper (Preußische Staats-Zeitung; note 6) many travelogues (an English

original; note 7); a biography of Peter the Great, and a church history for use

in schools.

German Pietist writings however dominate the collection’s religious materials, with song books, sermon collections, biblical studies, historical letters from the Moravian “Herrnhut” community, children’s stories (from Hernnhut; note 11), and resources for family worship by Johannes von Albertini (sermons from Herrnhut; note 12), Johann Arndt, Samuel Elsner, Christian Gottlieb Frohberger (letters from Herrnhut; note 13), August Spangenberg, Gerhard Tersteegen, and Johann G. Uhle among others. The latter materials complemented the Pietist influences incorporated into important eighteenth-century Prussian Mennonite publications, and would be the dominant theological influence—together with the later sermons of Pietist preacher Ludwig Hofacker (note 14) on the Russian Mennonite tradition as a whole, with the exception of the Kleine Gemeinde.

Other traditions were also represented in the Cornies library, including the medieval classic Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, a history of the Friends/Quakers (English; note 15), a German-language Russian Orthodox theology (note 16), and works by J. F. W. Jerusalem, whose enlightenment, non-dogmatic theological writings echo those of German Mennonite Abraham Hunzinger (note 17), plus a few philosophical-apologetic texts, as well as a work on the religion of Mohammed and the Koran (note 18).In 1836, eighteen percent of the Agricultural Society's budget over three years was used for the acquisition of books, agricultural journals, newspapers, and to prepare topographic sketches and maps (note 19). Cornies made many of the acquisition decisions and book orders personally, in all cases with the dual purpose of improving the colony "morally and economically" with reading materials in the areas of religion, history and economic/agricultural matters--as he reported to the President of the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers. With focus and commitment to broad, life-long education accessible for all in the colony, Cornies opened Mennonites to the larger world of ideas and best practices to remain a "model community," a light on a hill. This was his interpretation of the Mennonite call and purpose in Southern Russia. ---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes/ Sources---

Note 1: Johann Cornies, “Catalogue of Books—1841 [actually 1845; German; handwritten] .” In Peter J. Braun Russian Mennonite Archive, file 797, reel 34. From Robarts Library, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON. Also see: Johann Cornies, “Ueber die landwirtschaftlichen Fortschritte im Molotschner Mennoniten Bezirke in dem Jahre 1845 (Fortsetzung),” Unterhaltungsblatt 1, no. 2 (May 1846) 10, https://www.hfdr.de/sub/pdf/unterhaltungsblatt/1846_Teil-1.pdf .

Note 2: https://books.google.ca/books?id=nNY_AAAAcAAJ&dq=medizinisches%20handbuch&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Note 4: https://archive.org/details/naturgeschichte00raff/page/n3.

Note 6: ht,tps://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN657064149&PHYSID=PHYS_0005.

Note 7: https://books.google.ca/books?id=yhZUAAAAYAAJ&dq=michael%20symes&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Note 8: https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN657064149&PHYSID=PHYS_0005.

Note 9: In Menno Simons, The Complete Writings of Menno

Simons, edited by J. C. Wenger (Scottdale,

PA: Herald, 1984), https://archive.org/details/completewritings0000menn_b6u1/.

Note 10: Georg von Reiswitz and Friedrich Wadzeck, Beiträge zur Kenntniß der Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Europa und Amerika, Parts I and II (Berlin, 1821/1829), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009717700.

Note 13: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10449078-1.

Note 14: https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb10463596_00007.html.

Note 15: https://books.google.ca/books?id=aAxNAAAAcAAJ&pg=PP7#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Note 16: https://books.google.ca/books?id=My9fAAAAcAAJ&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Note 17: See previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/ideas-for-educational-reform-1832.html.

Note 18: See previous post on Cornies and Molotschna's Islamic Nogai neighbours, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/islamic-nogai-neighbours.html.

Note 19: Johann Cornies to Andrei M. Fadeev, January 28, 1837, in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters and Papers of Johann Cornies, 1836-1842, vol. 2, translated by Ingrid I. Epp, edited by John R. Staples, Harvey L. Dyck and Ingrid I. Epp (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), no. 40, pp, 37f. See also pp. 156, 434, 598, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/100164/1/Southern_Ukrainian_Steppe_UTP_9781487538743.pdf.

Comments

Post a Comment