The factors weighed by families leaving (or thinking of leaving) Russia in the 1870s for “America” were many. The presenting issue was the requirement of some form of obligatory state service.

But other factors were also at play and are well expressed in a series of letters from a Görtzen family in Franzthal, Molotschna to relatives already in Kansas.

- What will the neighbours do?

- What do our children and their friends want to do?

- What can we get for our farm? Will we have enough money?

- How cold is the weather there? Will we go hungry?

- Is there enough land for our children here in Russia?

- What will our son think of us when he's called up for state service?

- Is there more freedom there than here? Is it safe? What about Canada?

- Does anyone really know the future? What is God's will?

- Are the church fights (sheep stealing) worse there than here?

- The congregations here are all divided whether to stay or not.

Here are some excerpts:

“My wife and I are not able to do much work anymore. Here we

are still able to make a living, but will we be able to survive over there?”

“We have heard it is so cold in America that the potatoes

freeze right in the house.” “How much tax do you pay?”

Some say “things are just ‘so-so’ in America.” Here it is “a time for tears,” for “so many of us are forced to part with loved ones due to the emigrations” (note 1).

“If it is in God’s plans we will be coming to America. If

Pankratzes want to and if our children want to go with their friends then we

will probably go too, if we could all live close to one another. …"

“[Pankratz] actually is very scared of the future. If the

oldest son should be taken away [to the forestry] he would tell the father it

his fault. Many a father fears this. Others say there is no need; in three

years it [alternative service time] will be over. On account of that we will

not abandon our farms, go to America and go hungry. Those who don’t have much money

can really get into a poverty situation." (1877; note 2)

“[Pankratz] keeps thinking about how much it will cost and whether

things will really be safer in America than here. No one has written us that

there is absolute freedom in America because nobody knows for sure. From Canada

they wrote to [come] … because things in Canada are good. … Here in Russia

there are disagreements about land. … What is causing trouble today is the

disagreement in belief. There is practically no congregation that has unity in

that. It buzzes most of the time." (1878; note 3)

“It has been said that some of the older grey-haired fathers

and mothers who moved to Nebraska a year ago have been [re-]baptized. Ask

Tessmann … from Schardau who knows them well. Then write and tell us the truth.”

(Note 4)

In the end Anna and Franz Görtzen chose not to emigrate;

Anna framed these matters with her own understanding of the Last Days:

“I think punishment and rods from the Lord will strike us anywhere, here as well as in America. The way I read Holy Scripture … there will be no fleeing. So I have resigned myself completely” (note 5).

The letters give insight into the agonizing questions that every family wrestled with—and in the end some left, and others chose to stay.

One-third of Russian Mennonites did immigrate

to North America in this period. The new railways in Russia/Europe and also in

North America made immigration a plausible option. Most including

Bergthal colonists travelled via Odessa and Hamburg. In 1865-66 the first leg

of the railway from Odessa to the Ukrainian city of Balta was completed (180

km;). By the late-1870s this rail line was connected with the line to

Lviv (then Austrian “Lemberg”), and further west to the North Sea port city of

Hamburg, Germany (note 6; map).

Johann E. Peters from Kronsthal, Chortitza recalled his trip down the Dnieper River by boat and then a stormy sail on the Black Sea to Odessa in 1876. "Everyone thought we were lost but everyone on the ship prayed very hard to God and promised to be true to him forever. And God was merciful and saved us all, so we arrived in Odessa where I saw a train for the first time in my life. Then we took the train to Hamburg, Germany" (note 7).

The flow of extra trains arriving in Hamburg from Odessa throughout 1875 with migrating Mennonites was followed with some astonishment by the German press. “From now [June 1875] until the end of September, there will regularly be one or two extra trains arriving in Hamburg from Russia with emigrating Mennonites." Later in August a German newspaper item surmised that “the emigration of Mennonites from Russia continues on such a large scale, that there might soon no longer be any Mennonites remaining in that country” (note 8).

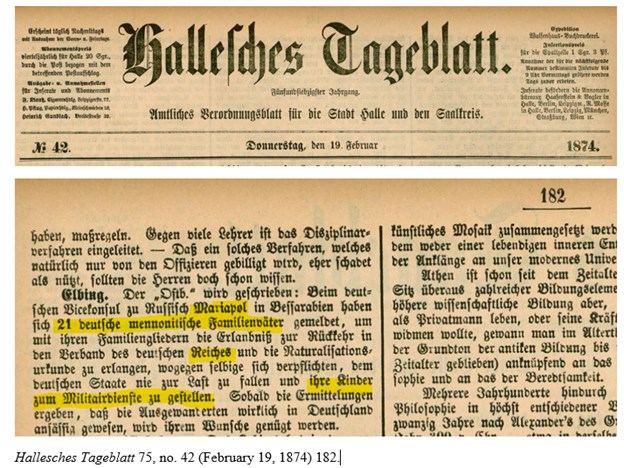

A German newspaper piece from February 1874 reported that 21 Mennonite heads-of-family applied in Mariupol (Bergthal area) for permission to “return” from Russia to the German Reich as naturalized citizens—with the understanding that their children would have to do military service (note 9).

This “complexifies” the familiar—or denominationally

sanitized—Mennonite accounts of emigration even more.

James Urry has argued that “it was not just the Russian

state that Mennonites were turning their back on, but also other Mennonites and

a Mennonite way of life which was being consciously rejected” (note 10).

And even more, David G. Rempel one of the first

university-trained historians of Russian Mennonite life—has argued:

1. The familiar Mennonite claim that the state’s new

policies were “anti-German” is false. The changes in law, education, military

service, etc., came in part as a response to “economic and social conditions”

for Russia’s “42,000,000 land-hungry” emancipated serfs and state peasants;

“Could any ruler have dared to ignore that tragic fact?”

2. Prior to 1874, Russian men (normally limited to serfs)

had to serve 25 years in the military and as reservists, “in addition to being

subject to billeting of troops in his home and village, feeding and

transporting of troops, etc.” In comparison, “all foreign colonists [e.g.,

Mennonites] were exempted from all these inequities.” While many Mennonites

perceived the change in their status as a betrayal, the state was driven “by a

sense of elementary justice,” Rempel argued.

3. With the Crimean War (1853-56) many Mennonites saw

first-hand “Russian inefficiency, indescribable corruption, [and] the brutal

treatment of the common soldier by his superiors.” Consequently not a few

Mennonites began to fear the possibility of a future peasant revolution,

according to Rempel (Note 11).

A report by the Tsar's adjutant General Eduard Totleben to

the Minister of the Interior noted the same, according to Rempel, that “fear of

eventual revolution,” i.e., fear that some might “demand to have the same

privileges and receive the same benevolent treatment which these outsiders

[Mennonites] had received for so long” was real according to Rempel. This

fear—together with russification policies and economic factors (land

availability)—“played a much greater role than the alleged religious motives

and opposition to make any compromise in respect to an alternative form of

service” (note 12).

Congregational conflicts, denominational divides, the

emancipation of serfs and fears of revolution, new concerns around

landlessness, shifts in farming and markets from sheep to grain, a change to

Russian as the colonial administration language, conflict over educational

developments initiated by progressives as well as by the state, business

prospects for Mennonite merchants, etc., all played a role in emigration—and

some were even willing to accept the conscription of their sons into Prussia

military rather than to stay in Russia.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Pic: Görtzen correspondence, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/03_1875_translated/20121115190352982_0023.jpg.

Note 1: From Görtzen correspondence from Franzthal,

Molotschna to Kansas, including: Franz Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, December

11, 1874; May 28, 1878; Anna Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, April 22, 1875.

Bethel College, Mennonite Library and Archives, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/.

Note 2: Franz

Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, February 20, 1877, 1f. https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/04_1877_translated.

Note 3: Anna

Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, May 28, 1878, 2. https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/05_1878_translated/.

Note 4: Franz

Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, May 28, 1878, 3. https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/05_1878_translated/.

Note 5:Franz

Görtzen to Heinrich Görtzen, February 20, 1877, 2. https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_283/04_1877_translated/.

Note 6: Map from Igor Zhaloba, "Chernivtsi-Odessa Railway Project: Idea and Reality of the 1860s" (Institute of International Relations of the National Aviation University, Ukraine), https://www.docutren.com/HistoriaFerroviaria/Vitoria2012/pdf/4011.pdf; the map is based on Louis Perl, Die Russischen Eisenbahnen im Jahre 1870/71 (St. Petersburg: Schmitzdorf, 1872), https://books.google.ca/books?id=9m5_wAEACAAJ&pg=PT2#v=onepage&q&f=true. Based on Nettie Kroeker's translation: "Grandfather Wiens’ Diary en route Russia to Canada: Diary of Jakob Wiens," Preservings 17 (2000): 41-44, https://www.plettfoundation.org/files/preservings/Preservings17.pdf. Original in Mennonite Heritage Centre Archives, Wiens Family Fonds, Vol. 22522253, 4580: 1-2, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/papers/Wiens%20family%20fonds.htm.

Note 7: John E. Peters (1865-1955), "Account of immigration trip of 1876," written in 1942/43, Mennonite Historical Society of Alberta, https://mennonitehistory.org/johann-e-peters/. Slightly edited.

Note 8: Hallesches Tageblatt 76, no. 140 (June 19, 1875), 708, https://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/zd/periodical/pageview/8861934;

also no. 177 (August 1, 1875), 881, https://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/zd/periodical/pageview/8862121.

Note 9: Hallesches Tageblatt 75, no. 42 (February 19, 1874), 182, http://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/zd/periodical/pageview/8859862.

Note 10: James Urry, “The Russian State, the Mennonite World and the Migration from Russia to North America in the 1870s,” Mennonite Life 46, no. 1 (March 1991), 11–16; 15, https://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1991mar.pdf.

Note 11: Letter, David G. Rempel to Lawrence Klippenstein, February 25, 1975, 2, in David G. Rempel Papers. Box 7, File 2. From Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Note 12: Letter, David G. Rempel to Lawrence Klippenstein, April 30, 1982; and D. Rempel, “‘Memorandum of General Adjutant Todleben Concerning the Mennonites,” 9, in David G. Rempel Papers. Box 7, File 12. From Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. See also previous posts: https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2022/09/turning-weapons-into-waffle-irons.html, and https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/1871-mennonite-tough-luck.html.

---

To cite this post: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "'Leave for Kansas? If the Pankratzes go we'll probably go too!' Letters 1874/78," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), June 10, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/leave-for-kansas-if-pankratzes-go-well.html.

Comments

Post a Comment