In the 1820s, Jacob Bräul (b. 1803) was a young teacher in Einlage, Chortitza. He had been a pupil here under the well-known teacher Heinrich Heese, his predecessor.

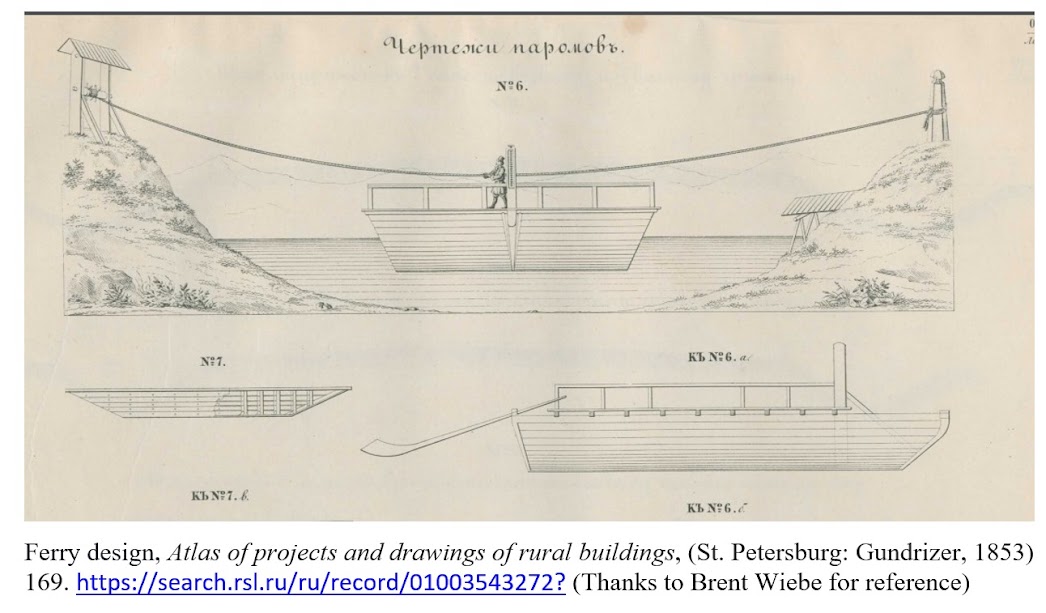

Because a teacher’s salary was generally between very low and tolerable—30 rubles a year plus some produce was the average—Bräul spent the summers as clerk and bookkeeper at the municipal ferry that crossed the Dnieper River from Einlage (Kitschkas) to Alexandrovsk / Zaporoschje.

The crossing formed part of the mail and stagecoach route to

Crimea, and the ferry was large enough to carry horses and wagons. Since the

days of Peter the Great, Russia had been a “well-ordered police state” (note 1)

with a passport system to collect information and control movement within the

empire; at the Einlage ferry-crossing passport numbers were recorded and

runaway serfs and occasional scuffles reported. Here Bräul had opportunity to

develop his Russian fluency.

The crossing was constructed in 1801 by the government and

given to the village of Einlage to operate on the condition that all

government-related crossings are gratis (note 2). Recognizing its potential,

the community invested its liquor distillery profits into “respectable ferries

on which everyone enjoys crossing” (note 3).

After three years of teaching, Heese became Chortitza District Secretary; he received an annual income of 500 rubles plus free housing in the colony offices.

The colony's revenues included 2,000 to 2,500 rubles from

the Dnieper ferry at Einlage, income from communal sheep and plantation

operations in Rosenthal and Burwalde, and a 1000 ruble annual lease for beer

and liquor distilleries in Einlage (note 4).

The location of the ferry was at the foot of Heinrich

Heese’s home; it was by all accounts, one of the more romantic settings on the

river—with cliffs and surrounded by oak and wild pear (Kruschke) trees (note 5).

This lower part of Einlage was flooded by unusually high

water levels in 1820.

Because of their location on the river, neighbours gave

these villagers the Low German nickname “catfish gnawers" (note 6).

In 1819, the larger Chortitza Settlement included 560 families with 2,288 individuals and 35,600 hectares of land. The colony had 470 residential homes, two churches, forty-nine windmills, 2,582 horses, 6,090 head of cattle, 11,774 sheep, 2,070 pigs, and 557 spinning wheels. The District Secretary counted and reported all of this (see note 4).

In 1828, Heese was brought before a "holy tribunal" of Chortitza officials, called "a devil" for his work, and chased out of Chortitza. Johann Cornies took the opportunity to snatch up Heese as new teacher for his high school in Ohrloff, Molotschna. Bräul followed in the same year to teach in Rudnerweide. They were the earliest Mennonite teachers in Molotschna competent to teach Russian.

--Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Cf. Marc Raeff, The Well-Ordered Police State:

Social and Institutional Change Through Law in the Germanies and Russia,

1600–1800 (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1983).

Note 2: “Chortitza Kolonie in den Akten des Fürsorgekomitees

in den Jahren 1799," no. 65, 1801-28, https://chortitza.org/Dat/Fuers.htm.

Note 3: Heinrich Heese, et al., “Das Chortitzer

Mennonitengebiet 1848: Kurzgefasste geschichtliche Übersicht der Gründung und

des Bestehens der Kolonien des Chortitzer Mennonitenbezirkes,” [Schluß], 75. https://chortitza.org/Ber1848.html#Eg.

Note 4: “Länder und Völkerkunde: Uebersicht der

ausländischen Kolonien in Neu-Rußland,” St. Petersburgische Zeitschrift 3, vol.

2 (Leipzig, 1824) 174–192; 288–301; 184f., https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/Pis/SPZ1824.pdf.

Note 5: Cf. “Heinrich Heese (1787–1868): Autobiography,”

translated by Cornelius Krahn, Mennonite Life (April 1969), 66–72; 68, http://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1969apr.pdf.

Note 6: Gerhard Wiens, “Village Nicknames among the

Mennonites of Russia,” Mennonite Life 25, no. 4 (October 1970), 177–180; 178,

179, http://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1970oct.pdf. The use of

nicknames for villages or people is an excellent window on the lighter side of

community life and the limitless creative possibilities for humour in the Low

German dialect.

---

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, “The Einlage Ferry,” History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), May 9, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/the-einlage-ferry.html.

Comments

Post a Comment