Molotschna Mennonite District Chairman David Friesen was invited to represent the Mennonites at the coronation of Tsar Alexander II in 1856. The extravagant pictures below are from the official coronation album (note 1).

I have translated the courtly letter of congratulations on behalf of “the entire Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia” signed by all nine church elders (but not Kleine Gemeinde) and two district chairmen (note 2).

"Most serene

and supremely powerful Emperor! Most Gracious Emperor and Lord!

May your Imperial

Majesty, Most Gracious One, be willing to accept our heartfelt congratulations

and thankful feelings, which we are so bold to lay down before the feet of the

Most High's illustrious throne in all humility, All Gracious One.

In the happy

knowledge that we, the whole Mennonite Brotherhood in southern Russia, with

sincere hearts and filled with thanksgiving, are true subjects of your Imperial

Majesty, we gladly follow with all our soul the inner drive of the heart, to

express reverently and in childlike manner before our Imperial Majesty, that we

owe our thanks for this noble peace [Crimean War had just ended], next to God's

all-wise guidance, to the most gracious and fatherly sentiments of your

Imperial Majesty, through whose blessings we feel constantly committed, and

especially for the upcoming coronation, to prayer with all inwardness, that God

the Lord would bestow the richest fullness of His blessings and gifts upon your

Imperial Majesty as well as upon our whole, passionately beloved Imperial

House, so that the reign of your Imperial Majesty may be long and blessed ...

Mindful of the privileges most graciously bestowed upon our Mennonite Brotherhood by the revered Emperor and Lord Paul in a Most High Decree of Grace (Privilegium) on the 6th of September, 1800, we will gratefully continue to show ourselves more and more worthy, and strive with all of the strength and means at our disposal, to secure the benevolence of the Most Gracious One (Emperor) toward us in the future as well, that we and our children may live a quiet and peaceful life in all godliness and respectability under the most gracious protection of your Imperial Majesty, as we have been so blessed to this day under your Imperial Majesty and His majestic, most-blessed ancestors.

May the Lord our

God fulfill in the richest measure our childlike prayers and wishes for a long,

happy and blessed life and rule of your Imperial Majesty and direct the heart

of your Imperial Majesty according to His divine [God's] good pleasure.

We are unspeakably

happy to be in deepest reverence your Imperial Majesty's most humble and most

faithful subjects, the Mennonite Brotherhood in southern Russia, in the name

and on behalf of the churches and district of Chortitza, Mariupol [Bergthal]

and Molotschna.

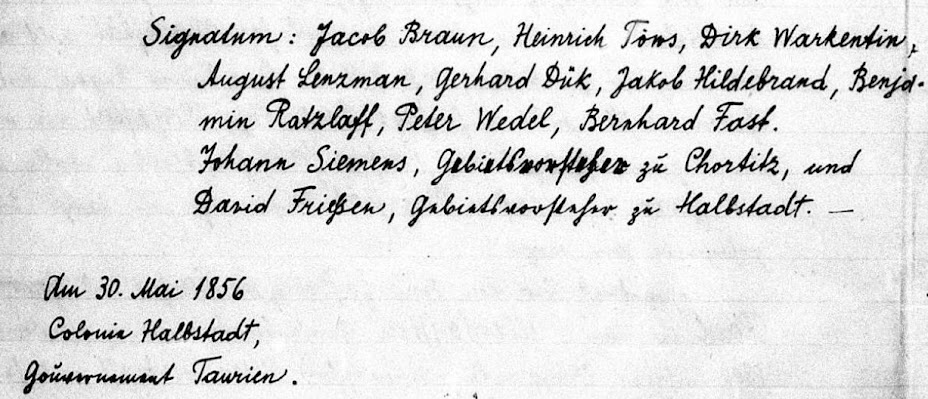

[Signatures --see attached pic]

Mennonite leaders were sincere in their praise, but not naive about the need to protect their charter of privileges with a new emperor. The congratulatory letter is a recommitment to the charter—that Mennonites will continue to show themselves “even more worthy” of the generous its privileges as a model community, and will strive toward that end “with all of the strength and means at our disposal.” And in return, their request is that the Tsar to be benevolent toward them, so that they and their children “may live a quiet and peaceful life in all godliness and respectability" under the Tsar's protection. This was not only wholly compatible with scripture (I Timothy 1:2f.), but also with their recently republished confession of faith and its article on “secular authority” (note 3).

To Russian Mennonites, the democratic revolutions across Europe appeared as chaotic eruptions that aimed to replace divinely ordained rulers with human institutions established on the “grace of the people” alone, not of God.

Popular evangelist

and poet-minister Bernhard Harder was convinced that the Russian monarch was a

divinely ordained bulwark against the “pestilence” and “vain and sinister

schemes of democrats” and “servants of Satan” (note 4).

When Alexander II was

assassinated in 1881, Russian Mennonites told their recently resettled siblings

now in America of their deepest grief at this “irreplaceable loss” at the hands

of “democrats” (note 5).

Years later after the 1905 Russian Revolution, historian P.M. Friesen described his Mennonite people as a “genuine Christian-conservative and generally bourgeois group,” among whom “ninety-nine out of one hundred … considered such words as ‘democrat,’ ‘democratic’ with suspicion, foreboding ill, and from a democracy only evil was expected” (note 6). While Friesen was articulating the prevailing opinion of Mennonite leadership, he was blind to the social unrest in large Mennonite factories, and the growing class distinctions among Mennonites in Russia.

--Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Coronation

Album, from Brown University Library, https://library.brown.edu/readingritual/totos.html.

Note 2: “Abschrift

der eingereichten Dankschrift der Mennoniten im südlichen Rußland an Sr.

Majestät den Kaiser Alexander II. vor der Krönung im August 1856,” Mennonitische

Blätter 4, no. 1 (1857), 5, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Blaetter/1854-1900/1857/DSCF0069.JPG.

Pics from copy of original in “Letters of Appeal to the Tsar, 1856–1866,” Peter

J. Braun Russian Mennonite Archive, Reel 52, File 1827.

Note 3: See “Article

XI: Concerning Secular Authority” of the United Frisian, Flemish, German

Confession, now known as the “Rudnerweide Confession,” https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Confession,_or_Short_and_Simple_Statement_of_Faith_(Rudnerweide,_Russia,_1853)#XI._Concerning_Secular_Authority

Note 4: Geistliche

Lieder und Gelegenheitsgedichte von Bernhard Harder, edited by Heinrich Franz (Hamburg:

A-G, 1888) vol. 1, no. 519, 566; no. 533, 583f. Regarding democratic assassins,

see poems no. 521, p. 568f., https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/Pis/Hard1.pdf.

Note 5: Cf. letters

from the villages of Fabrikerweise (Mennonitische Rundschau I, no. 23 [May 1,

1881], 1), Schönau and Halbstadt (MR I, no. 22 [April 15, 1881], 1), and Großweide

(MR II, no. 1 [June 1, 1881], 1), https://archive.org/details/pub_die-mennonitische-rundschau?query=&sort=week&&and[]=year%3A%221881%22.

Note 6: Peter M. Friesen, Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia 1789–1910 (Winnipeg, MB: Christian, 1978) 627; https://archive.org/details/TheMennoniteBrotherhoodInRussia17891910/.

---

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, “Coronation Day,

1856,” History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), May 9, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/coronation-day-1856.html.

Comments

Post a Comment