"In the Case of Extreme Danger

1. We are Russian-Mennonite refugees who are returning to Holland, the place of origin. The language is Low German.

2. The Dutch Mennonites there, Doopsgezinde, will take in

all fellow-believing Mennonites from Russia who are in danger of compulsory

repatriation.

3. The first stage of the journey is to Gronau in

Westphalia.

4. As a precaution, purchase a ticket to an intermediate

stop first. The last connecting station is Rheine.

5. Opposite Gronau is the Dutch city of Enschede, where you

will cross the border.

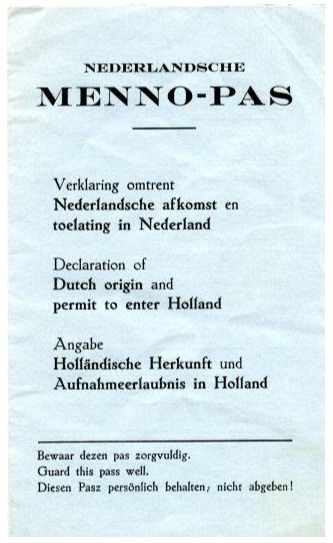

6. On the border ask for Peter Dyck (Piter Daik), Mennonite

Central Committee, Amsterdam, Singel 452. Peter Dyck (or his people) will

distribute the relevant papers—“Menno Passes”--and provide further information.

7. Any other border points may also be crossed, with the

necessary explanations (who, where to, Mennonites from Russia, Peter Dyck,

M.C.C., etc.). The Dutch border Patrol is informed.

8. Here the whole matter must be handled with the utmost

secrecy. It must not be made public because this can harm everyone, including

those who are already there. -02/16/1946." (Note 1)

Context (Hooge and Kornelsen memoir, note 1): “While we were in Müden, after

the war had ended, Russia tried to persuade us to return. But we Mennonites did

not want to return. This document was secretly given to us—I don’t know by

whom. … Back in October, 1945 one evening Peter Becker had come to us and said

that Jasch and my husband were supposed to get ready quickly to go along to a

meeting where a man from Canada, C.F. Klassen, wanted to talk to the men. He told

them then that if we ever were in great danger of being sent back to Russia we

should go to Holland. On February 14, 1946 a Russian Commissar came to Müden

and asked the Bürgermeister (mayor) to call together all the refugees from Russia … ”

Background

Immediately after the war the North American Mennonite

relief agency, Mennonite Central Committee, was actively looking for “its

people” in Germany—as was the Soviet Union. In cooperation with the United

Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the Red Cross, MCC special

commissioner C.F. Klassen, German Mennonite professor Benjamin H. Unruh, MCC

Europe Director Peter J. Dyck, and Dutch Mennonite leader T.O.H. Hylkema

began the work of locating and registering Mennonite refugees. Klassen was

named an “officer” of the British Red Cross, which enabled him to travel freely

by car through Germany and make first contact with the scattered Soviet

Mennonites, some of whom he found “living in stables, chicken barns, and even

pig sties” (note 2). Klassen’s fall 1945 reports to the Mennonite papers in

Canada enabled MCC to raise a large sum of money to help with the immediate

humanitarian crisis.

Klassen made contact with about 3,000 Russian Mennonite refugees, including the larger “Gnadenfeld group” in the Hermannsburg and larger Celle Region, and made contacts with the assistance of Jacob Neufeld, the Gnadenfeld group trek leader. On October 14, 1945, Klassen gathered specifically adult-male refugees and shared the short-term objective: “If I can get you to Holland, we could help you” (note 3). On August 1, 1945 some thirty-three Soviet Mennonites mostly from the village of Nieder-Chortitza had already been allowed to cross the Dutch border as “refugees of Dutch ancestry” (note 4).

On January 7, 1946, municipal leaders in and around Celle

received orders to make lists of all refugees who had been Soviet citizens

prior to 1939. “We were very upset about this and had reason to feel great

concern. In a few days’ time the Russian commissar became very active” (note 5).

Information had reached the refugees that British forces could no longer

protect the Soviet Germans from repatriation.

"On February 1st, a pastor in Celle, who was our negotiator with the English, came to see us. He said he could no longer help us and we must now look out for ourselves. A Canadian soldier came to see his relatives at night and told them they must try to get to Holland as quickly as possible, but to travel in small groups." (Note 6)

The Canadian solder—“Tjart,” also a Russian Mennonite—had

told them to travel to Gronau and gave them the address of the MCC office in

Amsterdam (note 7). Within the Molotschna refugee network in Celle word spread

rapidly that this family had left overnight. By February 3rd, almost all of the

Mennonite refugees housed in the suburbs of Wester-Celle and in Alten-Celle had

left.

Within the next two weeks news reached the Hermannsburg

group that more Soviet Mennonites were leaving for Gronau. Because they had no passport

or visa but only the following information on an unsigned page—likely via

Tjart, directly from MCC—which had been passed from family to family, they felt

extremely vulnerable.

Those who had left two weeks earlier recommended that others

pack only the most basic belongings in one hand-bag each, travel discreetly and

not in groups, and speak only high German—and not their Low-German dialect—when

buying their train tickets. Hosts who knew the destination of their Mennonite

guests expected the families would return because they had no passports or

visas which would allow them to enter The Netherlands, but only their Volksdeutsche

naturalization papers and ration cards for identification.

The Mennonites who gathered at the Hermannsburg train

station made an odd sight; the families agreed not to travel alone, but also to

act as if they did not know each other. My uncle Walter Bräul remembered how

strange it was to meet his mother Helene and sisters at the train station and

to act as if they were complete strangers! Because everyone was purchasing

tickets in the direction of Gronau, their primary concern was not to arouse the

suspicions of police or the ticket agents. One of the Mennonite men who at

first tried to enlist the others for repatriation meetings noticed that some

of “his people” were quietly packing and beginning to leave for some

unannounced destination. Everyone knew that this man should be told nothing.

Walter shared that at the train station this man and his wife began to

panic, thinking that they would be left completely alone. They began to weep

bitterly and they pleaded for forgiveness. They were eventually told of the

flight to The Netherlands and were graciously invited to join—which they did.

The route to Gronau included transfers at Hanover,

Bielefeld, and Osnabrück; the train cars were overcrowded with refugees from

Poland and Czechoslovakia. The Hermannsburg group held together discreetly and

arrived in Gronau on February 18, 1946.

MCC had hoped to get their refugees into The Netherlands for months before this crisis. With the support of the Dutch Mennonites, MCC officials worked to convince the new post-war Dutch government and the International Refugee Organization (IRO) that these refugees were not technically Soviet Germans or Volksdeutsche, but of Dutch origin. After years of racial propaganda exclaiming them to be biologically pure carriers of “German blood,” the Mennonite refugees were instructed to adopt another traditional descriptor: “[W]e were refugees from Russia. Our ancestors had come from Holland, and we would like to stay here until our relatives could help us over into Canada” (note 8).

MCC had to deal with questions of detail and argued, not without stretching the facts, that these Mennonites only became German citizens during the war under duress, and show that “naturalization had been conducted in a coercive environment.” Moreover, “since the Soviets did not recognize Russian Mennonites as German citizens and were eager to repatriate them as their own,” MCC Refugee Commissioner C.F. Klassen “saw no reason for the IRO to think otherwise” (note 9).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1 / Pic 1: In Selma Kornelsen Hooge and Anna Goossen

Kornelsen, Life Before Canada (Abbotsford, BC: Self-published, 2018), 79. My

translation--ANF

Note 2: Frank H. Epp, Mennonite Exodus (Altona, MB: Friesen,

1962), 366.

Note 3: Susanna Toews, Trek to Freedom: The Escape of Two

Sisters from South Russia during World War II, translated by Helen Megli

(Winkler, MB: Heritage Valley, 1976), 37; cf. Hooge and Kornelsen, Life Before

Canada, 78.

Note 4: Gerlof D. Homan, “‘We Have Come to Love Them’:

Russian Mennonite Refugees in the Netherlands, 1945–1947,” Journal of Mennonite

Studies 25 (2007), 39–59; 42; 40f., https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/1223/1215.

Note 5: Toews, Trek to Freedom, 38.

Note 6: Toews, Trek to Freedom, 38.

Note 7: Toews, Trek to Freedom, 39; also Katie Friesen, Into

the Unknown (Steinbach, MB: Self-published, 1986), 101f.

Note 8: Toews, Trek to Freedom, 40; cf. esp. Ted D. Regehr,

“Of Dutch or German Ancestry? Mennonite Refugees, MCC and the International

Refugee Organization,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 13 (1995), 7–25,

Note 9: Gerhard Rempel, “Cornelius Franz Klassen: Rescuer of the Mennonite Remnant, 1894–1954,” in Shepherds, Servants and Prophets: Leadership Among the Russian Mennonites (ca. 1880–1960), edited by Harry Loewen, 193–228 (Kitchener, ON: Pandora, 2003), 200.

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, “‘In the Case of

Extreme Danger:’ Menno Pass and Refugee Crisis, 1945-46,” History of the

Russian Mennonites (blog), May 10, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/05/in-case-of-extreme-danger-menno-pass.html.

Comments

Post a Comment