In 2008 the Canadian Parliament passed an act declaring the fourth Saturday in November as “Ukrainian Famine and Genocide (‘Holodomor’) Memorial Day” (note 1). Southern Ukraine was arguably the worst affected region of the famine of 1932–33, where 30,000 to 40,000 Mennonites lived (note 2). The number of famine-related deaths in Ukraine during this period are conservatively estimated at 3.5 million (note 3).

In the early 1930s Stalin feared growing “Ukrainian

nationalism” and the possibility of “losing Ukraine” (note 4). He was also

suspicious of ethnic Poles and Germans—like Mennonites—in Ukraine, convinced of

the “existence of an organized counter-revolutionary insurgent underground” in

support of Ukrainian national independence (note 5). Ukraine was targeted with

a “lengthy schooling” designed to ruthlessly break the threat of Ukrainian

nationalism and resistance, and this included Ukraine’s Mennonites (viewed

simply as “Germans”).

Various causes combined to bring on widespread famine and hunger in the countryside, including:

- forced collectivization and dekulakization after 1930;

- lack of machines, good work horses and cattle to meet quotas;

- administrative chaos;

- unrealistic grain collection campaigns to be fulfilled unconditionally (or heavy fines);

- deprivation of consumer goods to any village that failed to deliver grain;

- government denial of a looming crisis (blamed on “hoarders”);

- demoralization of workers;

- imposition of the death penalty in 1932 for those who ‘steal’ grain from the kolkhoz (note 6);

- introduction of internal passports to restrict rural workers from moving to towns (where there was more food).

Unfavourable weather conditions from 1931 to 1934 were also

part of the story. But there is broad scholarly agreement that Stalin and his

officials “magnified significant harvest shortages into a famine as an exercise

in state terrorism. The famine sent a blunt message to rural areas that the

government intended to control agriculture in the Soviet Union regardless of

the human or economic cost” (note 7). Mennonites co-witnessed each step of the

Holodomor’s implementation in Ukraine and were crushed together with their

ethnic Ukrainian neighbours (note 8).

Already in April 1930 Benjamin Unruh, a pivotal Mennonite relief

and immigration leader stationed in Germany, warned that “disaster threatens

the entire Mennonite population … there is a serious threat of famine in all Russia

[sic] within a year according to reliable estimates” (note 9). Nine months

later, Molotschna farmers were shooting stray dogs for food; many had already

lived “a whole year without a cow, without fat, without potatoes.” The response

from co-religionists in the west was immediate and generous with anonymous

gifts of cash, rice, flour, semolina, palm oil and bacon (note 10).

Susanna Toews of Gnadenfeld, Molotschna recalled that in

Summer 1931 they “harvested a tremendous crop, the largest in living memory,”

but after fulfilling unreasonable quotas they were without bread by January

1932 (note 11). The crisis only worsened and Unruh’s sources suggested that the

great famine of 1921–22 “was nothing” in comparison to the current situation.

One letter to Unruh stated: “If God does not do a miracle then, as humanly

foreseeable, in a short time we will all be dead, simply starved to death” (note

12).

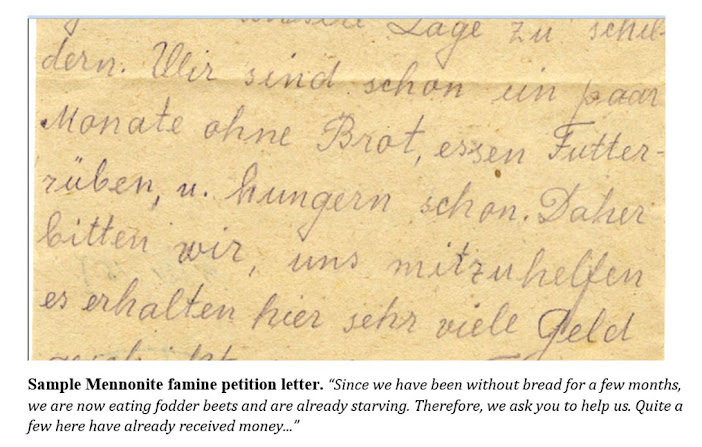

Thousands of Mennonites in Ukraine began to write letters to

the west petitioning for food (in a previous vignette we examined 146 such

famine letters written in January or February 1933; note 13). The requests

indicate that larger numbers of children were already suffering from

malnutrition, listless, pale, anemic with swollen bellies, and consequent

illnesses, including long fevers and typhus. The handicapped, ill, elderly, and

disenfranchised could not work, were not paid and did not eat, according to the

letters: “Since we have been without bread for a few months, we are now eating

fodder beets and are already starving” (note 14). We know that in some

Mennonite villages people were “coerced” to refuse aid packages or money sent

from abroad in 1933—and some who did accept them were arrested the next year (note

15).

The GPU (secret police) report in March 1933 recorded some

twenty-eight incidents of cannibalism, and there are indications that this may

have occurred in Mennonite areas as well (note 16).

There are many stories. Anecdotally a friend’s father recalled how he as a six-year-old boy ate tulip bulbs as well as the sap and buds from their fruit trees (note 17). My mother’s aunt by marriage Agatha Klassen Bräul wrote about the February 7, 1933 double funeral of her parents in Paulsheim: “At the burial we wanted to give lunch to the few relatives who came from outside the village, but we had nothing to offer except a few beets and some onions. We cooked a Borscht soup, and it was eaten to the last spoonful” (note 18). District party executive committees encouraged communist activists to recruit children, Young Pioneers and even the handicapped for special permanent committees to help locate hidden reserves of grain or food in the homes and yards of kolkhoz members (see sample pic). The mother of one friend, Katharina Heinrich Esau born in Franzthal, Molotschna, remembered how “a group was chosen to go from house to house, look through everything, and take whatever food stuffs were found. Consequently, people starved. There was already poverty prior to the famine. … I don’t recall where they [father and mother] hid the food. It was especially difficult for families with more children. I remember how some women came and begged or offered items in exchange in order to survive” (note 19). In Mennonitische Rundschau I was stunned to find a letter from my grandmother’s sister, pleading for aid:

“Schardau, Russia, October 1932. Since we are living in such a difficult time and the up-coming Winter looks so dark, and since we have been without bread for several weeks now, I want to be so bold and ask for a little help from abroad. Our need is driving me to do so. I am a widow with 3 children. The oldest is 7 years old, the second is 5 and the youngest girl is 3 years old. We are part of a collective. I must go to work every day because the food products we receive are only available on workdays, and even then, we receive so little. In a day we may only receive half a day’s portion [check translation]. There is nothing for the children. It is almost 3 years since my husband died. Our clothing situation is also pitiful. If someone can assist us, I thank you in advance. May the Lord reward you all. With greetings, Sarah Rehan, Schardau.” (Note 20)

These sisters were lived in close proximity to

each other (Marienthal and Schardau). My grandmother gave birth to a daughter

at the height of the famine (born June 1933), who died shortly before her first

birthday in 1934 (see pic). We do not know what she died of, but illness, malnutrition

and death were widespread. A 1934 letter sent to the Mennonite press in North

America reported that in the Molotschna “755 families ate horse meat, 469

families ate crows, 344 families ate cats and 184 families ate dogs from the

spring of 1932 to the summer of 1933” (note 21).

These stories represent only a few of the many Mennonite

memories of the Holodomor. While Mennonites in Ukraine were not always in synch

with their Ukrainian neighbours, in this event they were one, and Mennonites

can stand “as Ukrainians” and remember their own people who suffered together

with all Ukrainians under a brutal regime.

---Notes---

Note 1: For the text of the Act of Parliament, see: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/u-0.4/page-1.html.

Note 2: Cf. Stalin, “Resolution on Grain Procurement in

Ukraine, 19 December 1932;” “Memorandum on Progress in preparing Spring

Sowing,” in Bohdan Klid and Alexander J. Motyl, eds., The Holodomor Reader: A

Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Edmonton, AB: Canadian Institute

of Ukrainian Studies Press, 2012), 5:25, 37, https://holodomor.ca/the-holodomor-reader-a-sourcebook-on-the-famine-of-1932-1933-in-ukraine/.

Note 3: Cf. R. W. Davies and Stephen Wheatcroft, The

Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. The Industrialisation of Soviet

Russia, vol. 5 (New York: Macmillan, 2009).

Note 4: Stalin, “Seventeenth Party Congress, 26 January

1934,” in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor Reader 5:32f.; Stalin, “Telegram of

28 December 1932,” in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor Reader, 5:27.

Note 5: “On the Need to Liquidate the Insurgent Underground,

February 13, 1932,” in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor Reader, 5:32f.

Note 6: Cf. “On Safekeeping Property of State Enterprises

[and] Collective Farms, 7 August 1932,” in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor

Reader, 5:17.

Note 7: Jenny Leigh Smith, Works in Progress: Plans and

Realities on Soviet Farms, 1930–1963 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

2014), 22.

Note 8: On the Mennonite experience, see esp. Colin

Neufeldt, “The Fate of Mennonites in Ukraine and the Crimea during Soviet

Collectivization and the Famine (1930–33),” PhD dissertation, University of

Alberta (1999), ch. 4, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp04/nq39574.pdf.

See also previous post on Mennonite deaths due to starvation, as well as aid

received (forthcoming).

Note 9: Benjamin H. Unruh to Levi Mumaw, MCC, and David

Toews, Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, April 1, 1930, p. 2. Letter.

From MCC-A, IX-03-02, box 2, file 1.

Note 10: Abraham Dueck, “Our Village: Hierschau,” in The

Silence Echoes: Memoirs of Trauma and Tears, translated and edited by Sarah

Dyck, 34–46 (Kitchener, ON: Pandora, 1997), 41; Mennonitische Rundschau (April

22, 1931), 7, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1931-04-22_54_16/page/n5/mode/2up;

sample thank-you letters in Mennonitische Rundschau (November 18, 1931), 6f., https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1931-11-18_54_46/page/6/mode/2up.

Note 11: Susanna Toews, Trek to Freedom: The Escape of Two

Sisters from South Russia during World War II, translated by Helen Megli

(Winkler, MB: Heritage Valley, 1976), 15f.

Note 12: Letter to Benjamin H. Unruh, cited in Henrich B.

Unruh, Fügungen und Führungen: Benjamin Heinrich Unruh, 1881–1959: Ein Leben im

Geiste christlicher Humanität und im Dienste der Nächstenliebe (Detmold: Verein

zur Erforschung und Pflege des Russlanddeutschen Mennonitentums, 2009), 368.

Note 13: See previous post (forthcoming).

Note 14: Peter Joh. Martens, Schönau February 4, 1933, in

Hermann R. Schirmacher, ed., "Bittbriefe aus Russland bzw. Ukraine Anfang

der 30er Jahre aus dem Archiv von Professor Benjamin Unruh Karlsruhe,"

Chortitza: Mennonitische Geschichte und Ahnenforschung, https://chortitza.org/FB/BUBBriefe_Karlsruhe.php.

From Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe, 7/Nl Unruh.

Note 15: Cf. “Neu-Halbstadt (Zagradovka) Dorfbericht,” 207,

in “Village Reports Commando Dr. Stumpp,“ in Bundesarchiv Koblenz, R6, files

620 to 633; 702 to 709.— https://invenio.bundesarchiv.de; or https://tsdea.archives.gov.ua/.

Note 16: Cf. “Report from the GPU Ukrainian SSR on problems

with food supplies and raions of Ukraine affected by famine, March 12, 1933,”

in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor Reader, 7:36; and O.V. Grytsina and T. V.

Marchenko, “The Holodomor in Southern Ukraine in 1932–1933” [Голодомор на

Півдні України у 1932–1933], in Holodomor 1932–1933: Zaporizhzhya Dimension [Голодомор

1932–1933: запорізький вимір], 65–80 (Zaporizhia: Prosvita, 2008), 72, http://history.org.ua/LiberUA/978-966-653-209-4/978-966-653-209-4.pdf.

See also previous post (forthcoming). Archivist Conrad Stoesz notes that

Aganetha Wiebe letters at the Mennonite Heritage Archives also hint at

cannibalism.

Note 17: Jakob Esau in Erich Schmidt-Schell, Trotzdem macht

Gott keine Fehler: Jakob Esau. Wegen des Glaubens in Russland verfolgt und

geächtet (Meinerzhagen: Friedensbote, 2010), 8.

Note 18: Agatha Klassen Bräul, Diary (copy in author’s

possession).

Note 19: Katharina Heinrichs Esau, “So bleibt es nicht.

Erinnerungen aus meiner Kindheit [bis 1945],” 2002. In author’s possession, pp.

5-6. On the initiative, cf. “Conditions in Northern Caucasus in Spring of 1933;

Report by Otto Schiller, German Agricultural Attaché in Moscow, 23 May 1933,”

in Klid and Motyl, eds., Holodomor Reader, 5:47. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org.

Note 20: Sarah Rehan, Schardau, Mennonitische Rundschau 55,

no, 38 (Nov. 1932), https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1932-11-30_55_48/page/6/mode/2up.

Note 21: Cited in Colin P. Neufeldt, “Fate of Mennonites in

Ukraine and Crimea,” 249; “The Public and Private Lives of Mennonite Kolkhoz

Chairmen in the Khortytsia and Molochansk German National Raĭony in Ukraine

(1928–1934),” 58, in The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies,

no. 2305 (2015), DOI: https://doi.org/10.5195/cbp.2015.199.

Comments

Post a Comment