By March 1944, some 35,000 Mennonites in Ukraine had been evacuated by Nazi Germany and resettled mostly in German-annexed Poland. Here they came under the spiritual oversight of the Mennonite churches in the German Reich, and granted its same racial and religious privileges. This vignette gives a glimpse of the pro-Nazi orientation and commitments of Mennonites in Germany (note 1).

Praise for Germany’s territorial expansion and the unity of

German people—with the triumphant entry of the Führer Adolf Hitler into Austria—topped

even the Easter message in the April 1938 issue of the denominational paper, Mennonitische

Blätter (note 2).

“To the throne of the Most High we raise our hearts and

hands for our Führer and for our whole people (Volk) with the petition: ‘May

the Lord our God be with us as he was with our ancestors; may he never leave us

nor forsake us. May he turn our hearts to him, to walk in obedience to him and

keep the commands, decrees and laws he gave our ancestors’ (1 Kings 8:57f.).

[Signed] Emil Händiges, Chair, Vereinigung (Union) of German Mennonite

Congregations.”

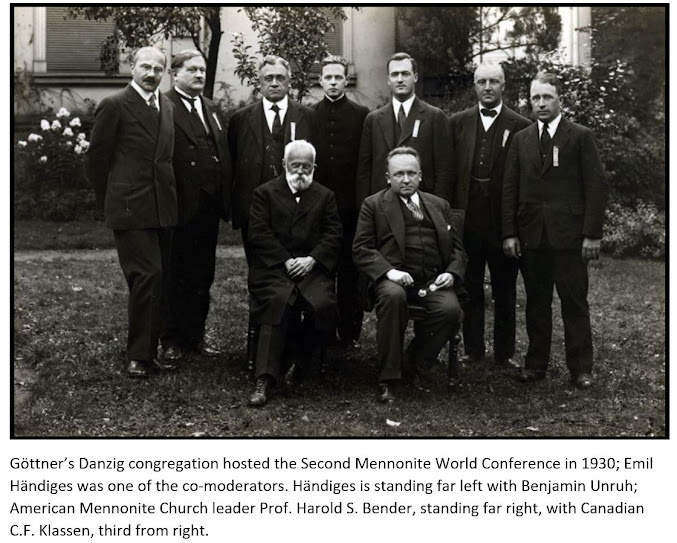

The same year, only days before the bloody Reichskristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) pogrom in November, Danzig Mennonite Pastor Erich Göttner presented a key note

address in the large Heubuden, West Prussian Mennonite church—deeply aware of

the gravity of the times and the responsibility of being placed by God into a

“specific Volk (ethnic people)—our German Volk;” for the call of Christ “to

stay alert” spiritually for what is arising in the present and its driving

forces; for the goal-oriented, unified coordination of all national energies

[totalitarianism]; for the cultivation of race [aryanism] and kinship, and for

need to participate with all one’s strength, and be salt and light.

The foundations of faith were shaking and Göttner was aware

that for many young adults the churches were simply not keeping pace, seen as

“outdated, museums in which the air of the past blows; they hold fast to

ossified doctrines and stand removed from the vibrant momentum of the present;

they fight over words and teachings, instead of acting practically … robbing us

of the unbroken joy in life, and making us inwardly divided and powerless, to

enemies of the world and culturally inept” (note 3).

Göttner was also aware that in the upheavals and questions

of the day many of their own young adults found the language of the Bible

distant, alien and irrelevant to their lives. They were bombarded with the most

diverse worldviews each with competing claims about ultimate reality and the

shape of a good human life. He pointed to the attraction of atheism or

agnosticism in reductionist scientific worldviews, but also to the Volk-centred

religiosity which derives religion from race and nation.

The conclusion that both he and his Elbing colleague Elder Händiges

drew was that their Mennonite-Christian youth can be gospel-flavoured “salt”

for the inner renewal of Volk and Fatherland; that they can coordinate their

energies with those outcomes of the “total state.”

But Göttner reminded readers: to stay alert, to recognize

the spiritual battle, to read scripture with Christ as the one foundation, to

learn and be inspired by the sixteenth-century Anabaptists. Good advice.

Five years into Hitler's rule things had clearly turned a

corner and there was much to "celebrate". On the five-year anniversary of the

raise of National Socialism, the recently retired Pastor Gustav Kraemer of

Krefeld noted that the arts are now accessible to all, and Germans are learning

to sing again—and not simply Mardi Gras songs or Berlin hits. Movies and

magazines have been purged of smut and obscenities. The fine arts are no longer

“dependent on the praise or ridicule of Jewish media bandits” or subject to

“the defilement and devastations of perverse demons.” Kraemer pointed to the

early Anabaptist movement as a purely German Christian movement. He saw a

direct parallel between the Anabaptist emphasis on being salt and light, and

the “positive Christianity” affirmed in the Nazi Party

platform—“life-affirming, active, creative Christianity" (note 4).

Händiges noted that same year that "a number of well-respected members of the Mennonite ministerial wear the Swastika [pin] with pride and joy as Party members" (note 5).

In 1933 when Hitler had seized power there were approximately 13,000 Mennonites in the German Reich, with another 6,000 in the Free City of Danzig and a further 1,000 in neighbouring regions. Upon becoming Chancellor, Prussian Mennonites sent official congratulations to Hitler:

“The Conference of the East and West Prussian Mennonites

meeting today at Tiegenhagen in the Free City of Danzig are deeply grateful for

the tremendous uprising that God has given our people (Volk) through your vigor

and action, and promise our cooperation in the construction of our

Fatherland, true to the Gospel motto of our fathers, 'For no one

can lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus

Christ.’” (Note 6)

Hitler responded in a letter received by

Elder Franz Regehr, Tiegenhof:

“[From] The Reich Chancellor, Berlin, September 1933. I would like to express my sincere thanks for the loyal attitude that you expressed in your letter and your willingness to work on building the German Reich. -Adolf Hitler.” (Note 7)

Hitler was explicitly introduced to Mennonites six years later in 1939 when the City of Danzig was “returned” to the German Reich—including the larger Mennonite communities of Heubuden, Ladekopp, Orlofferfelde, Fürstenwerder and Rosenort. Long-time Nazi Party member and Tiegenhagen Mennonite Church member Otto Andres was named Lieutenant Governor of Danzig-West Prussia in Fall 1939 under the new Governor and Regional Party Leader Albert Forster.

Hitler entered Danzig triumphantly on September 19, 1939

following Germany’s attack on Poland. Forster welcomed Hitler officially at the

“Artushof” in Danzig, where Hitler gave a major speech (see pic; note 8).

After the official program, Hitler was guest of honour in

the Party Chancellery on Jopen Street. Heubuden Mennonite Church member and

elected District Administrator for Marienburg, Walter Neufeldt, was invited for

this VIP reception with Hitler, and here he spoke to the Führer directly about

the Mennonites. In 1976 Neufeldt told Horst Gerlach—Mennonite teacher and

historian, Weierhof—about the encounter. Here are Gerlach’s notes:

“Gauleiter Forster, Marienburg District Administrator Walter

Neufeldt, District Educational Leader [Wilhelm] Löbsack [Reich Propaganda

Office], historian Professor [Walther] Recke, several senators and other people

were present. In the course of the conversation, the topic of the persecution

of Huguenots in France came up, and then the topic of sectarians. In this

context, Löbsack also referred to the Mennonites as positive forces in the

history of religion. They came from the Netherlands, cultivated the Danzig

Delta and then many moved to Russia and achieved great colonizing successes in

the Ukraine—similar to those in the Delta. While Löbsack was saying this, he

pointed to Neufeldt and said: 'And a person from this sect just happens to be

sitting right there.' Hitler was surprised because he had not heard about the

Mennonites. He had Neufeldt briefly explain to him their most important basic

beliefs. Neufeldt then enumerated a number of principles: lay-ministerial

leadership, according to which the preachers and elders are elected from within

the congregation; the cohesion of the congregation and the support of the whole

for the individual who is in need. He mentioned the persecutions suffered in

the Netherlands for the sake of faith, and the rejection of the oath. He also

mentioned that Mennonites who broke their word were expelled from the church.

Hitler listened to all of this. He was particularly

impressed by the principle of the lay-ministerial leadership. He also found the

unconditional support of the community for the individual and the expulsion of

those who break their word from the community worthy of recognition. Literally

he said: 'Future religious founders should take something like this as an

example' [Löbsack had opened the conversation by asking Hitler to become

a founder of a religion --Götz Lichdi]. Hitler instructed Gauleiter Forster to

send him further documents about the Mennonites. Forster passed this order on

to District Administrator Neufeldt. He then collected documents via Elder

Heinrich Dyck and Deacon Gustav Reimer, both from the Heubuden Mennonite

Church. Professor Keyser from the Technical University of Danzig-Langfuhr added

to this collection of material about the Mennonites, and then the whole file

was passed on to Hitler. Neufeldt never found out what effects - positive or

negative - this conversation or the submitted materials had. Neufeldt

subsequently met Hitler two more times. But Hitler never returned to the subject

of Mennonites." (Note 9)

Hitler may not have known much about the Mennonites, but by

this point (1939) Mennonites were very familiar with Hitler. A 1937 public

statement reprinted in the Mennonitische Blätter, for example, reaffirmed the

“unconditional loyalty” of German Mennonites to the Führer and the Third Reich,

and identified the following marks of the broader Mennonite tradition:

baptizing upon personal confession of faith; following Christ in a new life of

obedience; rejecting external coercion in matters of faith; and committing to

truthfulness in word and deed. The latter is the “foundation for all morality,”

the statement reads, and its sign is the rejection of oaths, as per Matthew

5:34-37. The approved wording of the “pledge” of unconditional obedience to

Hitler is given in full. The text affirms that Mennonites “honor worldly

authority and human order,” and believe it is “a Christian obligation to serve

conscientiously Volk and state” (note 10).

This was the nazified German Mennonite world into which Mennonites extracted out of Ukraine were received and supported (note 11).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: See previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/first-christmas-for-black-sea-germans.html.

Note 2: Emil Händiges, "Das ganze Deutschland soll es

sein!," Mennonitische Blätter 85, no. 4 (April , 1938), 7, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Blaetter/1933-1941/DSCF1228.JPG;

see also his speech on the 50th anniversary of the denomination a few weeks

earlier, Mennonitische Warte: https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Warte/DSCF3670.JPG.

Note 3: Erich Göttner, “Der Ruf der Stunde an unsere

Gemeinden,” in Gemeindeblatt der Mennoniten 70, no. 2 (January 15, 1939), 6-9;

and part II, 70, no. 3-4 (February 1, 1939), 12-14. https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Gemeindeblatt%20der%20Mennoniten/1933-1941/DSCF7800.JPG;

Emil Händiges, “Jugendfürsorge,” in Mennonitisches Lexikon II, edited by C.

Hege and C. Neff, 441–445. (Frankfurt a.M./Weierhof, 1937), 444; 441: “Whoever

has the youth, has the future. The Anabaptists knew and took heed of this truth

early on … .” See also previous post on German Mennonites and Kristallnacht, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/01/holocaust-remembrance-day-january-27.html.

Note 4: Gustav Kraemer, Wir und unsere Volksgemeinschaft 1938, Lecture delivered in Heubuden, January 25, 1938 (Krefeld: Consistorium der Mennonitengemeinde Krefeld, 1938), 8; 21, 23, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/books/1938,%20Kraemer%20Wir%20und%20unsere%20Volksgemeinschaft/. Cf. “National Socialist German Workers’ Party Program,” § 24.

Note 5: Emil Händiges, June 23, 1938 to Vereinigung

Executive and Daniel Dettweiler, in Mennonitische Forschungsstelle Weierhof,

Vereinigung Collection, folder 1938.

Note 6: “Bericht über die 4. allgem. westpr. Konferenz in

Tiegenhagen am 10. September 1933,” Mennonitische Blätter 80, no. 10 (October

1933), 101,

Note 7: “Die Antwort der Reichsregierung auf die

Begrüßungsgtelegramme der Konferenz zu Tiegenhagen, Freie Stadt Danzig,” Mennonitische

Blätter 80, no. 11 (November 1933), 109, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Blaetter/1933-1941/DSCF0884.JPG.

Note 8: Hitler Speech in Artushof, Danzig, September 19, 1939,audio: https://archive.org/details/19390919AdolfHitlerRedeImArtushofInDanzig1h02m; English: https://der-fuehrer.org/reden/english/39-09-19.htm.

Note 9: Interview by Horst Gerlach/Weierhof with Walter Neufeldt on August 2, 1976, in Ahrensburg by Hamburg, in Diether Götz Lichdi, Mennoniten im Dritten Reich. Dokumentation und Deutung (Weierhof/Pfalz: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1977), 60, https://archive.org/details/mennonitenimdrit0000lich/.

Note 10: “Grundsätzliches über die deutschen Mennoniten,

über ihre Stellung zu Wehrpflicht und Eid, und ihr Verhältnis zum Dritten

Reich,” Mennonitische Blätter 84, no. 10 (October 1937), 72-74, 73, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Blaetter/1933-1941/DSCF1181.JPG.

In 1938 Mennonites were recognized by the Nazi regime like the larger churches

as a specifically Christian denomination, and that Mennonites did not need to

swear an oath to become a member of the Nazi Party (Mennonitische Warte 4, no.

42 [June 1938], 231, https://chortitza.org/pdf/vpetk366.pdf).

Note 11: See previous posts, as well as my published essay “German

Mennonite Theology in the Era of National Socialism,” in European Mennonites

and the Holocaust, edited by Mark Jantzen and John D. Thiesen, 125–152 (Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 2020).

Comments

Post a Comment