The landless crisis in the mid-1800s in the Molotschna Colony is the context for most other matters of importance to its Mennonites, 1840s to 1860s. When discussing landlessness, historian David G. Rempel has claimed that the “seemingly endemic wranglings and splits” of the Mennonite church in South Russia were only seldom or superficially related to doctrine, and “almost invariably and intimately bound up with some of the most serious social and economic issues” that afflicted one or more of the congregations in the settlement (note 1).

It is important from the start to recognize that these Mennonites were not citizens, but foreign colonists with obligations and privileges that governed their sojourn in New Russia. For Mennonites the privileges, e.g. of land and freedom from military conscription, were connected to the obligation of model farming. Mennonites were given one, and then later two districts of land for this purpose. Within their districts or colonies, villages were to be created in which families received equal allotments of land in perpetuity. Each village had between 20 and 30 farmsteads (Wirtschaften) which could not be divided or sold, but only inherited by one son in perpetuity (note 1b).

A district also had reserve land for future villages

according to population growth, or to be rented, e.g., for sheep grazing. Every

village was also required to set aside 1/6 of their land as surplus land for other

housing (e.g., the old and retired) and trades. Because other sons did not

inherit a farm, a father was responsible to prepare them for other trades

needed to create whole communities. Importantly, all land—surplus, reserve and

ultimately each farmstead—belonged to the Mennonites as a whole, governed at

the village and district levels. Under Russian law governing foreign colonists

(the Ukaz of March 1764; note 2), and within the more specific obligations and

privileges of their unique charter (Privilegium), and as diligently directed

and supported by the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Colonists to meet their

obligations, farmers could flourish—or also forfeit their family’s farmstead.

A person unfit to farm and fulfill the mandate of the

charter at a local level—i.e., as a model, flourishing farming community—would

after much assistance and warning be removed from the farmstead which would be

given to another. Reasons varied: desire to farm, age, physical fitness,

attitude, work ethic, willingness or ability to learn, etc. could be factors (examples in note 3).

The Guardianship Committee could appoint special committees

from within a colony with overriding authority in economic, agricultural or

educational matters, e.g., directing exactly how and what to plant, how and

what to build or teach for example. Johann Cornies was famously appointed as

Chairman for Life of the Agricultural Society with overwhelming authority

granted from the Guardianship Committee—which grew as his accomplishments and

those of the Molotschna impressed authorities (note 4).

Decisions about surplus and reserve land and their rents were made locally, but policy, direction and pace were unclear from the start.

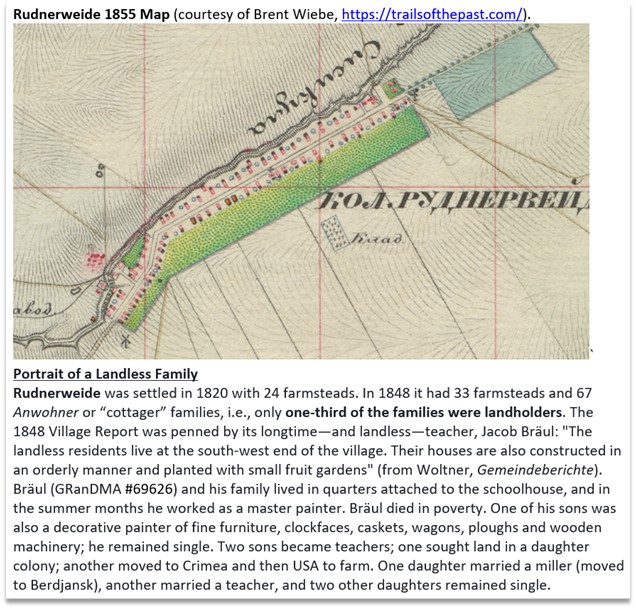

Only those with a farmstead could vote in village or district affairs. Items for decision might include use of reserve land in the village and surplus land for the district; the head-tax rate; contributions to communal grain storage (even by the landless), and imposed communal fines, labour or imprisonments—e.g., for inability of the landless to pay rent to graze a cow on common pasture land (note 5). Given the many children in a typical Mennonite family, villages soon had a significant minority—and by 1860 almost two-thirds—of residents who were not landholders and who could not vote. Surplus lands were slow to converted to new villages in part because they provided lucrative rental lands for farmers with wealth. Governing authorities were reticent to push colonies on the pace of these developments.

Cornies and others had a vision for commercial agriculture supported by labour-intensive cottage industries, which later included the establishment of the craftsmen’s village of Neu-Halbstadt in 1842; weavers, millers, blacksmiths, cartwrights, furniture-makers, carpenters, shoe-makers, and cobblers were the largest categories of its artisans (note 6). But by the 1840s as new markets developed, only a few of the landless artisans kept pace economically with their siblings or cousins who inherited the farm. Arguably this led to the development of small manufacturing industries (especially in the Chortitza Colony), but in Molotschna that was a minority, and soon there was a surplus of craftsmen as well (note 7).

Moreover, with the shift from sheep to grain farming, farms needed a pool of cheap local labourers and it was to the benefit of voting landholders to keep this supply high. Because of the proximity of a new harbour

at Berdjansk and the growing price for wheat across Europe, those with a farm

became wealthy.

Those without land could not easily leave the colony to find

other land or a future in the cities of Berdjansk or Odessa; they required

passports which were rarely granted, and still remained under the governance of

the Mennonite charter.

For years cheap land could be rented by the landless for grazing from the neighbouring Nogai, but in the early 1860s they left en masse for Turkey (note 8) and Crown settled their land with emancipated Russian peasants and Bulgarian colonists.

Increasingly the smaller “cottager” village lots originally

intended for the old and retired were filled with younger families. Not

surprisingly by the early 1860s the Molotschna was on the brink of social

collapse. Some criticized the craftsmen for their relative poverty—they should

band together in societies or union, for example (note 9), and others the

labourers for an apparent lack of effort. Opinions were polarized, even among

the Kleine Gemeinde (note 10).

“Only in 1866 when the quarrel over this question was at its

height in the Mennonite colonies [villages] on the Molochnaia did it interpret

the colonists’ system of land ownership as obliging the communities to purchase

land for their landless people. For one reason or another the government [had]

never enforced the provisions of the [1764] March Ukaz …” (Note 11)

After the death of “enlightened despot” Johann Cornies in 1848, and with the illness of his heir in that role, son-in-law Philip Wiebe, “the control of the most important offices [of the colony] was now completely in the hands of the shortsighted, selfish men who in many instances could barely read and write” (note 12). David G. Rempel pulls no punches in his assessment of the new leadership:

“The new chairman of the Agricultural Commission, Peter

Schmidt, was as egotistic and unscrupulous an individual as David Friesen, the

district head [he was removed from office]. Both treated the [landless]

petitioners with contempt, telling them bluntly that they would not permit the

unoccupied land to be distributed as desired by the landless, since that would

deprive the landowners of their source of cheap labour.” (Note 13)

District Chair Friesen was removed on corruption charges;

State Assessor Islavin saw evidence of a clientele system, in which the

chairman and the landowners who alone could elect him benefitted financially

from each other’s support.

Land ownership determined social status—a problem in a

community defined in its charter as Mennonite, ostensibly with all the church mechanisms needed to level social disparities (adult baptism for females and

males; all baptized males could elect or be elected as ministers and elders and

speak on church disciplinary [ethical] matters including banning from Lord’s

Supper and expulsion). The landless in fact sought assistance from the

clergy—who were mostly well-to-do, for there was no compensation; “but here, too,

they found no better response to their grievances” (note 14).

Chortitza’s tensions around land were not as extreme,

assisted in part by the early establishment of the Bergthal daughter colony and

the Judenplan (note 15).

New villages were established on reserve lands in Molotschna the following years: 1851 Nikolaidorf, 1852 Paulsheim, 1854 Kleefeld, 1857 Alexanderkrone, Mariawohl, Friedensruh, and Steinfeld, 1862 Gnadental, and 1863 Hamberg and Klippenfeld (note 16). Yet the creation of new villages could hardly meet demand—190 weddings were celebrated in 1860 alone (note 17).

The state was compelled to intervene, and officials strongly

condemned the Mennonite administration and landowners—though there were

outliers, like Wiebe. Not only was all remaining surplus and reserve land to be

reallocated to the landless, but smaller-sized farms, or “half farms,” were now

possible as well (this reminds me of the movie!). Despite these moves,

conflicts continued, e.g., about use of common grazing land.

In the 1870s daughter colonies became a defining

characteristic of the Russian Mennonite story, though the legal and political

situation (status of colonists now as citizens and land ownership laws) had changed

drastically with the Great Reforms (note 18). Again complaints of favouritism

arose with the selection of settlers for new colonies (note 19). Over the next

decades before the First World War, Chortitza and Molotschna would establish

some fifty daughter colonies across Tsarist Russia, including in the Ukraine,

the Caucasus, the Volga Region, Siberia and Central Asia (note 20).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: David G. Rempel, “Disunity and schisms in the

Mennonite Church ca. 1789 -1870.” Unpublished typed manuscript, p. 2. From

David Rempel Papers, Box 39: 20, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of

Toronto. Toronto, ON.

Note 1b: See James Urry, "Land Distribution" (1989), GAMEO, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Land_Distribution_(Russia).

Note 2: In the provisions of the Russian Land Ukas of March

19, 1764 concerning land tenure and inheritance for foreign colonists, families

were given land as an inheritable possession but “not personally to any one

colonist, but to each colony as a whole, with every family merely enjoying the

use of its allotted portion in perpetuity” (David Rempel, “The Mennonite

Colonies in New Russia. A study of their settlement and economic development

from 1789–1914,” PhD dissertation, Stanford University, 1933, 105, https://archive.org/details/themennonitecoloniesinnewrussiaastudyoftheirsettlementandeconomicdevelopmentfrom1789to1914ocr).

Note 3: See previous post (forthcoming)

Note 4: See previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/11/johann-cornies-enlightened-despot-of.html.

Note 5: Alexander Klaus, Unsere Kolonien: Studien und

Materialien zur Geschichte und Statistik der ausländischen Kolonisation in

Rußland, translated by J. Töws (Odessa: Odessaer Zeitung, 1887), 269-269,

271-272, http://pbc.gda.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=16863; OR https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/?file=Pis/KlausD.pdf.

Note 6: For complete statistics for 1844, cf. August von

Haxthausen, Studien über die innern Zustände, das Volksleben und insbesondere

die ländlichen Einrichtungen Rußlands, part II (Hannover: Hahn, 1847), 189, https://archive.org/details/studienberdiein03kosegoog/;

and Friedrich Matthäi, Die deutschen Ansiedlungen in Rußland. Ihre Geschichte

und volkswirthschaftliche Bedeutung (Leipzig: Fries, 1866), 200, https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_gCkEAAAAYAAJ/page/n225/mode/2up.

Note 7: Rempel, “The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia,” 184.

Note 8: See previous post (forthcoming)

Note 9: Samuel Kludt chastised the landless craftsmen for

not banding in societies or unions to buy product, market, sell transport, for

example, Mennonitische Rundschau (MR) 3, no. 14 (July 15, 1882), 1, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1882-07-15_3_14/page/n1/mode/2up?q=landlosen;

continued in MR 3, no. 15 (August 1, 1882), 2, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1882-08-01_3_15/page/n1/mode/2up.

Note 10: Cf. Abraham Thiessen, Die Agrarwirren bei den

Mennoniten in Süd-Rußland (Berlin: Wigankow, 1887), https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/kb/thiess.pdf;

idem, Die Lage der deutschen Kolonisten in Russland (Leipzig, 1876), https://mla.bethelks.edu/books/289_747_T344L.pdf;

Also: Cornelius Krahn, “Abraham Thiessen: A Mennonite Revolutionary?,” Mennonite

Life, 24 (1969), 73-77, https://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1969apr.pdf;

Delbert Plett, Storm and Triumph: the Mennonite Kleine Gemeinde, 1850-1875 (Steinbach,

MB: D.F.P Publications, 1986), chapter 8, https://www.mharchives.ca/download/1575/.

Note 11: Rempel, “The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia,”

106f.

Note 12: Rempel, “The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia,”

186.

Note 13: Rempel, “The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia,”

186: “Schmidt's father had obtained from the Guardians Committee a long-term

lease to 4,600 desiatine of the district’s reserve land, for which the son kept

on paying two kopeks per desiatin State rent, but leased most of it to the

landless colonists for three to four rubles per desiatin.” By subletting land

that belonged to the entire community to the landless, Schmidt (and others)

could generate significant profits which did not return to the community

treasury. The poor became poorer and the rich richer.

Note 14: Rempel, “The Mennonite Colonies in New Russia,”

186.

Note 15: On the Bergthal Colony, cf. previous post

(forthcoming); on the Judenplan, cf. previous post (forthcoming).

Note 16: Franz Isaac, Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten. Ein

Beitrag zur Geschichte derselben (Halbstadt, Taurien: H. J. Braun, 1908), 26, https://mla.bethelks.edu/books/Molotschnaer%20Mennoniten/; OR https://archive.org/details/die-molotschnaer-mennoniten-editablea;

English translation by Timothy Flaming and Glenn Penner, https://www.mharchives.ca/download/3573/.

Note 17: Mennonitische Blätter 8, no. 3 (May 1861), 34, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Blaetter/1854-1900/1861/DSCF0227.JPG.

Note 18: For this entire thematic, cf. James Urry, “Context,

Cause and Consequence in Understanding the Molochna Land Crisis. A Response to

John Staples,” Mennonite Life 62, no. 2 (Fall 2007), https://mla.bethelks.edu/ml-archive/2007fall/;

and John Staples, “Putting ‘Russia’ back into Russian Mennonite History: The

Crimean War, Emancipation, and the Molochna Mennonite Landlessness Crisis,” Mennonite

Life 62, no. 1 (2007), https://mla.bethelks.edu/ml-archive/2007spring/staples.php.

Note 19: “Etwas über Landankauf,” MR 5,

no. 2 (January 9, 1884), 1, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1884-01-09_5_2/mode/2up?q=landlosen.

Note 20: Besides the sources already noted above, cf. also

Jeffrey Longhofer, “Specifying the Commons: Mennonites, Intensive Agriculture,

and Landlessness in Nineteenth-Century Russia,” Ethnohistory 40, no. 3 (Summer

1993), 384–409; and Dmytro Myeshkov, Die Schwarzmeerdeutschen und ihre Welten:

1781–1871 (Essen: Klartext, 2008), 116-127.

---

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "Landless Crisis: Molotschna, 1840s to 1860s," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), November 7, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/11/landless-crisis-molotschna-1840s-to.html.

Comments

Post a Comment