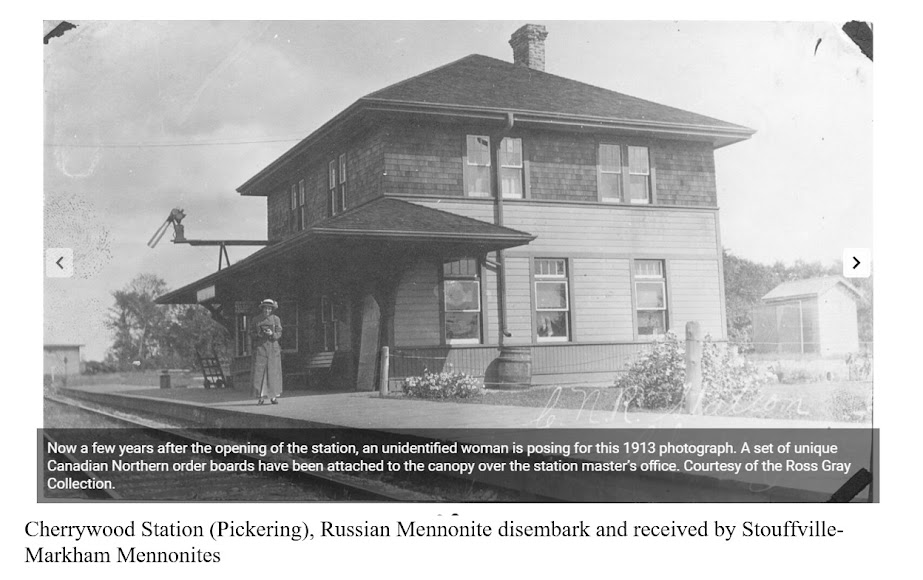

On September 26, 1924, 126 Russian Mennonite passengers disembarked the S. S. Melita at Quebec City (note 1). They were among some 20,000 Mennonites who could immigrate to Canada from the Soviet Union in the 1920s. A number of these families received train cards to Cherrywood (Pickering) and Locust Hill (Markham) stations, where they were received by Markham area Mennonites. The Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization (CMBC) registration forms record each family's travel dates as well as their "first place of arrival" in Canada.

The attached artifacts—a few pages from the financial records booklet kept by Markham-Stouffville treasurer J. L. Grove, plus some correspondence—profile concretely the level of support of this community north-east of Toronto for co-religionists fleeing

the Soviet Union.

Mennonites in Ontario had been well informed of the relief needs in Russia since 1921 and plans for mass immigration (note 2). In April 1924 the local Stouffville Tribune also published an article announcing that some 5,000 Mennonites from Russia were to arrive in Canada this year and settle [winter] in “Waterloo, Lincoln and York [including Markham and Stouffville] Counties” (note 3).

The article hints at the recently rescinded (1922) Order in Council (1919) which had identified Mennonite “customs, habits and modes of living” as barriers for the assumption of “the duties and responsibilities of Canadian citizenship”—namely public school attendance and conscription in times of war (note 4). “The Mennonites are a thrifty people and if they conform to Canadian laws will make good citizens. They have expressed a willingness to become good Canadian citizens.” The article explains that the Canadian Pacific Railway’s deal to transport the large groups of Mennonites from Russia is based on their successful experience with groups in the 1870s: “The C.P.R. is taking them from the Baltic ports and will transport them to Montreal for $140 a head, and the money need not be paid for two years, each signing a note to that effect on landing at Montreal. Twenty years [sic] ago a batch were brought out on similar conditions and not one of them defaulted. … The Russian Government is favorable to their leaving their leaving the country to which they must never return” (note 5).

That earlier group of Russian Mennonites were also housed initially with Mennonites in Ontario. In the spring of 1875 one group was escorted to Manitoba by Markham Mennonite saw- and gristmill proprietor Simeon Reesor —a cousin to the influential senator in the new Canadian government, David Reesor (note 6).

J. L. Grove’s records have been preserved by his son Lorne of Stouffville. They list the Russian Mennonite families whose first introduction to Canadian life and Mennonite hospitality was in Markham and Stouffville: Dyck, Isaak, Kasdorf, Käthler, Klassen, Krause, Löwen, Martens, Nachtigal, Neufeld, Poetker, Penner, Reimer, Rempel, Rogalsky, Schroeder, Suckau, Suderman, and Warkentin families (see full details below).

Typically after the first winter, the families moved on to the prairies. These families settled in the Manitoba

communities of Arnaud, Glenlea, La Salle, Niverville, St. Agathe, Whitewater,

Winkler, and Winnipeg; and in Saskatchewan communities of Drake, Hirsen,

Waldheim and Rosthern.

The Canadian government had sought guarantees from the larger Mennonite community that the newcomers would settle on the land as farmers (though many had not been involved in agricultural pursuits in Russia); that none would become a public charge for five years; and that they would be cared for upon arrival by their co-religionists.

Through the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, the Kanadier (1870s immigration group), the “Swiss” Old Mennonites of Ontario, the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren, the Kleine Gemeinde, as well as American Mennonite organizations were prepared by and large to assist in financing. The number of possible immigrants was still uncertain, but in 1921 there were about 120,000 Mennonites in Russia and about half that many in Canada (note 7). The public discrimination against Mennonites in the aftermath of WW1 served to bind Canadian Mennonite groups and also to galvanize support for famine relief and for those able to flee the Soviet regime.

Canadian Mennonite immigration leader Bishop David Toews of Rosthern had

earlier proposed a shareholders’ society to raise ten million dollars,

estimating that some 100,000 North American Mennonites would be willing to buy

$100 shares; $30 would be paid immediately by shareholders, and the balance

would be borrowed from the government. Aid recipients would repay the principle

with interest to a maximum of 5%. This scheme was met with significant skepticism

in places, especially in southern Manitoba and the US (note 8). In 1924 loans were requested to help

pay an immediate debt to the CPR (note 9).

Treasurer Grove received seven $100 contributions, six $50 contributions, and seven $25 contributions, plus another $1,260 collected by Joseph Barkey. “Shareholders” included families with the names Nighswander, Diller, Wideman, Houser, Reesor, Burkholder, Culp, and Smith.

Over the next years, Grove received remittances

from these specific Russländer families through the Canadian Mennonite Board of

Colonization—with a very few accounts not settled until after the Great

Depression towards the end of World War II. Most families had paid in full, but

collection was difficult from a few:

"January 21, 1929. Dear Brother Grove: … With regard to the other notes that have not yet been paid, we may say that in some cases our immigrants have had a very hard start and they have not been able to make any payments, although they are very anxious to repay their loans. Last year’s crops looked very promising but, as you know, the early frost did a great damage, so that in many places in Saskatchewan and Alberta the crops turned out very poor. In many instances the people will hardly have enough to get through the winter with their families. In general we may say that our immigrants are willing to pay and we are sure that they will do their best. If they had one good crop, they would try to repay their loans as far as possible. We trust you understand the position of the people. We on our part will do all we can to collect the outstanding monies as soon as possible. Yours very truly, Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization."

The stories of these encounters in the Markham area have

largely been lost. The Stouffville Tribune offers only a few episodes.

“Mr. and Mrs. Chas. Hoover, Mr. and Mrs. Doner with some of the Russian friends attended the service at Dixon Hill on Sunday” (October 30, 1924, note 10).

“Rev. P. Nachtegal [sic] will preach to the Russian people in this section in their own language next Sunday in the church at Dixon Hill. Service is at three o’clock” (November 6, 1924; note 11).

“Gormley: … Ed. Leary who had a 15 acre patch of potatoes, purchased a new International digger, and engaged a number of Russians, and took?” up his potatoes at the rate of 200 bags a day” (November 13, note 12)

“Ninth Line Markham: … Mr. R. Johnson has rented his house vacated by Mr. and Mrs. Reynolds a couple of weeks ago to some Russians” (December 4, 1924, note 13).

After a “winter internship” in the Markham area, the paper gives a few glimpses of the way in which Russian Mennonites left for western Canada.

“A packed house greeted the Russian Mennonites on Sunday evening of last week at the Mount Joy Mennonite church, when Rev. A. Nightingale (Nachtigall) preached an impressive sermon. The service was interspersed with a number of musical selections by the Russian singers, which were greatly appreciated. An address of appreciation, written by Rev. Nightingale and translated into English, was read by Rev. W. H. Yates, the pastor. The Russians which include several families, left this week to settle in southern Manitoba, where they are being provided with land and equipment.” (March 19, 1925, Note 14)

Not only did they have a minister in their group in Markham, but the group also had a number of formerly wealthy estate owners and farmers who were not afraid of a larger land purchases.

“Farm Deal of Some Magnitude: Last week Mr. Isaac Pike of Bethesda, took several of the Russian families from this locality to Markham, where the main body of them entrained for Western Canada to take up farm lands. Seven families from this section have undertaken what looks like a gigantic task and to some of the local Mennonites it looks almost like an impossibility. These families have banded together and purchased 2800 acres of land south of Winnipeg, at $40 per acre, totalling $112,000 which also includes the stock on the place, consisting of 60 cattle (some only yearlings) forty horses one tractor, one threshing outfit, sufficient implements, and all necessary seed grain for this spring planting. There is on the property four barns and four houses. As there was no initial payment, the interest charges alone will exceed $6000 the first year. It is said that these families are willing workers, but even then their financial obligation is so great that only a bumper crop would put them away to anything like a fair start this year. However, we all wish them well, and it can be said of them that if it is a possible undertaking at all, these are the people to make it go." (March 26, 1925, Note 15)

The Markham area Mennonite congregations were not large; in 1925 Almira Mennonite

Meeting House had 95 members, Reesor Mennonite Meeting House had 95, Cedar

Grove had 25 and Wideman 107 members (note 16).

The financial records above give evidence of a broader, common

ethos of trust, hospitality, generosity and commitment to support co-religionists

fleeing oppression.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: List of those Mennonites who disembarked at Quebec

City, September 26, 1924, https://www.grandmaonline.org/GMOL-7/searches/gmShipSearch.asp?shipName=S.%20S.%20Melita&shipDate=26%20September,%201924).

Cherrywood Station (pic), demolished 1964, https://www.trha.ca/trha/history/stations/cherrywood-station/;

Locust Hill (pic), original station destroyed by fire in 1935, https://www.trha.ca/trha/history/stations/locust-hill-station/.

Note 2: On the beginnings of the immigration movement, see previous post, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/02/immigration-to-canada-1923-background.html. See also the “Relief Notes” published regularly on Russia throughout 1924 and 1925 in the denominational paper, Gospel Herald, https://archive.org/details/gospelherald192417kauf/page/42/mode/2up?q=russia.

Note 3: “5000 Mennonites will come to Canada this Summer,” Stouffville

Tribune, April 24, 1924, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98321/page/363541?q=russia.

Note 4: On Order in Council, see Peter H. Rempel, “Mennonite

Cooperation and Promises to Government in the Repeal on Mennonite Immigration

to Canada 1919–1922,” Mennonite Historian 19, no. 1 (March 1993), 7, https://www.mennonitehistorian.ca/19.1.MHMar93.pdf.

Note 5: “5000 Mennonites will come to Canada this Summer.”

Note 6: Cf. Isaac Horst, “Colonization in the 1870s,” Ontario

Mennonite History 16, no. 2 (October 1998), 19–23; 20f., https://www.mhso.org/sites/default/files/publications/Ontmennohistory16-2.pdf.

Note 7: Cf. Sam J. Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands

(Kitchener, ON: Herald Press, 2015), ch. 4. The 1921 Canadian census tracked religion and the Stouffville Tribune reported that “[t]he Mennonites,

including the Hutterites, are among the religious sects which are more than

holding their own in Canada. There were 31,797 of this belief according to the

census of 1901 in Canada. This had increased to 44,611 in 1911 and to 58,797 in

the next decade” (Stouffville Tribune, April 9, 1925, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98368/page/363967?q=mennonites).

Note 8: See H. H. Ewert to Wilhelm J. Ewert, May 18, 1923, letter,

from Mennonite Library and Archives-Bethel College, MS 6, folder “General

Correspondence 1923, January to June,” https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_6/026%20General%20correspondence%201923%20January-June/140.jpg.

Note 9: S. Hallmann, “Mennonite Immigration to Canada from

Russia,” Gospel Herald 17, no. 2 (April 10, 1924), 42, https://archive.org/details/gospelherald192417kauf/page/42/mode/2up?q=russia. See also explanation by the CMBC executive

board, Mennonitische Rundschau 48, no. 3 (January 21, 1925), 10, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-21_48_3/page/10/mode/1up.

See also Frank H. Epp, Mennonites in Canada, 1920–1940: A People’s Struggle for

Survival (Toronto: MacMillan, 1982), https://uwaterloo.ca/grebel/sites/ca.grebel/files/uploads/files/mic_iir_0.pdf.

For the entire "exodus" story, see Epp's masterful Mennonite Exodus

(Altona, MB: Friesen, 1962).

Note 10: Stouffville Tribune, October 30, 1924, p. 8, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98346/page/363776?q=russian.

Note 11: Stouffville Tribune, November 6, 1924, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98347/page/363778?q=russian.

Note 12: Stouffville Tribune, November 13, 1924, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98348/page/363787?q=russian.

Note 13: Stouffville Tribune, December 4, 1924, p. 4, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98350/page/363808?q=russian.

Note 14: Stouffville Tribune, March 19, 1925, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98365/page/363940?q=russians.

Johann Dick spent the first winter in Markham (see obituary for Johann P. Dick,

d. 1952, in Mennonitische Rundschau 75, no. 30 [July 23, 1952], 1, https://archive.org/details/diemennonitischerundschau_1952-07-23_75_30/mode/2up);

Gerhard Klassen spent three years with Markham Mennonites (see GRanDMA profile,

#41289); Gerhard Dyck and family remained in the Markham area permanently.

Note 15: Stouffville Tribune, March 26, 1925, p. 1, https://news.ourontario.ca/WhitchurchStouffville/98366/page/363949?q=mennonites.

Note 16: 1925 membership statistics are given in respective GAMEO.org articles. For leadership in these congregations, cf. Mennonite Year-Book and Directory (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House); 1924, https://archive.org/details/mennoniteyearboo15unse_0/;1925, https://archive.org/details/mennoniteyearboo16unse_0/.

---

Some of the Russian Mennonite families who were first received at the Cherrywood or Locust Hill Stations include the following:

Dyck, Anna (Kliewer) (b. 1873, #1024484) and family of Kleefeld,

Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by contract). First

location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0999a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0999b.jpg.

Dyck, Helene (Woelk) (b. 1884, #208670) and family of

Eichenfeld (left after massacre, 1919), arrived at Quebec City, September 26,

1924. First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON,

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1499a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1499b.jpg.

Dyck (Dick/Dueck), Johann Peter (d. 1889, #426853) and

family of Ohrloff, Molotschna; arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled

by contract). First location in Canada: Locust Hill, ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0992a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0992b.jpg.

Epp, Johann (b. 1874, #755600) and family of Altenau, Molotschna;

arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by contract). First location

in Canada: Locust Hill, ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0998a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0998b.jpg.

Käthler, Wilhelm Peter (b. 1893, #151629), and family of

Liebenau, Molotschna; arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by

contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1498a.jpg,

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1498b.jpg.

Klassen, Gerhard (b. 1862, #41289), and family of Davidsfeld,

arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by contract). First location

in Canada: Locust Hill (Markham), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0990a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0990b.jpg;

https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-14_48_2/page/18/mode/2up?q=locust.

Klassen, David (b. 1888, #53447) with family, of Ohrloff, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, August 8, 1924 (travelled by contract). First location in Canada: Locust Hill, ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1100s/cmboc1127a.jpg; https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1100s/cmboc1127b.jpg; Family no. 290, Mennonitische Rundschau, January 28, 1925, “Beilage,” https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-28_48_4/page/17/mode/1up.

Krause, Jacob Heinrich (b. 1869, #419412), and family of

Hochfeld (left August 31 via Chortitza), arrived at Quebec City, September 26,

1924 (travelled by contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering),

ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1500s/cmboc1503a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1500s/cmboc1503b.jpg.

Loewen, Bernhard Aron (b. 1888, #1029049) and family of

Kleefeld, Molotschna, landed at Quebec City, October 10, 1924 (travelled by

contract). First location in Canada: Locust Hill (Markham), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1600s/cmboc1678a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1600s/cmboc1678b.jpg.

Nachtigal, Abraham Peter (b. 1866, #405647) and family of

Alexanderkrone, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled

by contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1496a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1496b.jpg.

Neufeld, Kornelius Peter (b. 1874, #100788) and family of Fürstenwerder,

Molotschna, arrived at St. John, January 25, 1925 (credit not indicated). First

location in Canada: Cherrywood, ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1700s/cmboc1788a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1700s/cmboc1788b.jpg;

https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-03-04_48_9/page/18/mode/2up?q=cherrywood.

Penner, Helena (Kornelsen) (b. 1888, #683543) and family, of

Tiegenhagen, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924. First

location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1488a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1488b.jpg.

Penner, Peter Jakob (b. 1898, #1021574) and family of

Rückenau, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by

contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON,

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1480a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1480b.jpg.

Petker, David (b. 1882, #68552) and family of Lichtfelde,

Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by contract).

First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1489a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1489b.jpg

Reimer, Agnes (Klassen) (b. 1871, #42048), and family of

Davidfeld (estate), arrived at Quebec City, August 29, 1924 (did not travel by

contract). First location in Canada: Waterloo, ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1700s/cmboc1762a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1700s/cmboc1762b.jpg.

Rempel, Wilhelm (b. 1866; #144888) and family of Lichtfeld, Molotschna;

arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (contract: not indicated). First location

in Canada: Locust Hill, ON (Ringwood), https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1000s/cmboc1079a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1000s/cmboc1079b.jpg;

(family 243) https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-14_48_2/page/20/mode/2up.

Rogalsky, Johann (b. 1888, #149534) and family of

Rudnerweide, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by

contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON,

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0996a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0900s/cmboc0996b.jpg;

Sudermann, Wilhelm (b. 1887, #357436) and family of Halbstadt,

Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by contract).

First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1485a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1485b.jpg.

Sukkau, Heinrich (b. 1877, #478991) and family of

Rückenau, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by

contract). First location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1494a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1494b.jpg.

Warkentin, Jakob, (b. 1866, #1014237), Tiegenhagen, Molotschna,

arrived at Quebec City, September 26, 1924 (travelled by contract). First

location in Canada: Cherrywood (Pickering), ON, https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1486a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1400s/cmboc1486b.jpg.

The following family is listed in Grove’s accounts, but has

not yet not been positively identified.

Wall, Johann.

The following two families are not listed in Grove’s accounts,

but are listed as living in Markham-Stouffville in the Mennonitische Rundschau’s lists of 1924 immigrants:

Wiens, Jakob (#407933, 1887) with family, from Tiege,

Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by contract). First

location in Canada: Waterloo (cf. CMBC forms) and (later 1924) Stouffville (cf.

MR, family #13), https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0800s/cmboc0848a.jpg;

https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/0800s/cmboc0848b.jpg.

List of 1924 immigrants to Canada, Mennonitische Rundschau, January 14, 1925, “Beilage,”

family no. 13, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-14_48_2/page/16/mode/2up.

Klassen, David (b. 1903, #693901) with two brothers, of Halbstadt, Molotschna, arrived at Quebec City, July 17, 1924 (travelled by contract). First location in Canada: Waterloo (CMBC) and (later 1924?) Markham (cf. MR, family #206), https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1000s/cmboc1042a.jpg; https://www.mharchives.ca/holdings/organizations/CMBoC_Forms/1000s/cmboc1042b.jpg. List of 1924 immigrants to Canada, Mennonitische Rundschau, January 14, 1925, “Beilage,” family no. 206, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1925-01-14_48_2/page/16/mode/2up.

Comments

Post a Comment