In the 16th century, the term “Mennonite” was adopted by several Anabaptist groups after the tolerant Countess of East Friesland, Anna von Oldenburg, insisted on distinguishing between the “fanatical” Münsterite Anabaptists, on the one hand, and Menno’s peaceful adherents—the Menniten—on the other (note 1).

In 1534, Anabaptists who found refuge in Münster had attempted to establish an “Anabaptist kingdom,” the “New Jerusalem,” in part with he forceful uprooting of the ungodly (note 2). This new holy city was marked by a variety of excesses including polygamy and the community of goods as they awaited the end-time apocalyptic battle between good and evil. This ended disastrously: the armies of the bishop besieged the city and, once inside, killed almost all the men. The three leaders were caged, severely tortured, displayed throughout the country, and put to death six months later.

The next year another 300 Münsterites, and possibly Menno’s

brother, occupied a monastery in Friesland near Bolsward, where 37 were

beheaded immediately, and another 54 later.

For next generations in Royal Prussia, an obsession with

status quo together with rigorous and frequent application of the ban led the

Frisian Mennonites to refer disparagingly to their more rigorous Flemish

brethren as “Münsterites.” But critiques by the Frisians did not bother the

Flemish, apparently, whom the Flemish referred to as “rubbish carts” (Dreckwagen)—for

they picked up any kind of smutty Mennonite (note 3)!

Moreover, some Mennonites in Prussia did “not like to call themselves

Mennonites,” but rather Taufgesinnte or “baptism-minded.” They did not want to

be known as originating from the fanatical and militant Münsterite Anabaptists

of the 16th century (note 4). Others alternately spoke of themselves as “quiet in the land”

in contrast to the militant Münsterite revolutionaries of old (note 5),

One of the first elders in Chortitza, David Epp, had a very

difficult first year as elder. His misdemeanors were detailed in a lengthy

letter of formal complaint dated September 1793 to elders in Danzig and Prussia

and endorsed by nineteen signatories. The elder’s leadership was responsible

for “causing dissension, hate and strife and the like,” and the writers even

compared Epp and his supporters with the militant, theocratic Anabaptist “Münsterites”

(note 6).

After the Russian Revolution, Mennonite leader Benjamin

Unruh wrote that “Bolshevik putschism” stands in direct continuity with the

revolutionary “sectarian” Anabaptism of Münster. Both could employ violence (“social

revolution with the sword of Gideon”) as a strategy for inaugurating the new

world order. In “genuine” Anabaptism, in contrast, the congregation is similar

to a “shock troop and bearer of an unbroken devotion to the final goals” and

“coming ‘order of God,’” but it is “never the kingdom of God” itself, according

to Unruh (note 7). Ironically Unruh was writing (positively) about shock troops

in a context in which Nazi shock troops in Germany were first having an impact.

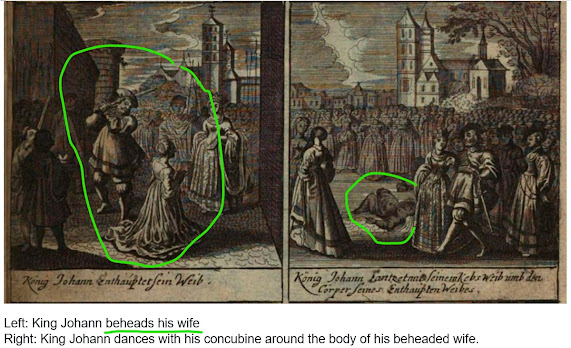

With this context it is not surprising that others

too produced hate literature that conflated Mennonites and Münsterites to warn against the murderous errors of "new” Anabaptists. In 1701, etchings known as the "Warning

Mirror" (Warnungs-Spiegel) were produced—a kind of mirror opposite of the

copper-plate etchings of the Martyrs Mirror by Jan Luyken (d. 1712; note 8).

Below are some of those etchings that warn earnestly against

"new Anabaptists," including Mennonites, Quakers, Pietists, atheists,

polygamists and many more heretics and arch-heretics.

The etchings function a little like extreme political

cartoons in our day, but here with the message that though the Old Anabaptists “may

be dead, but their spirit and legacy is still to be eradicated!"

And in Mennonite circles if you are looking to start a new schism,

remember that the “ultimate putdown” after many centuries is still to call your

fellow Mennonite a Münster-ite (or alternatively a Dreckwagen, depending on

context or perspective).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Anna Oldenburg-Delmenhorst, Countess of East

Friesland, “On the Treatment of Sectarians,” February 15, 1545. In A. F.

Mellink, ed., Documenta Anabaptistica Nederlandica, Part I: Friesland en

Groningen, 1530–1550 (Leiden: Brill, 1975) I, 190.

Note 2: Cf. Walter Klaassen, Living at the End of the Ages.

Apocalyptic Expectation in the Radical Reformation (New York: University of America

Press, 1992), 45-51, https://archive.org/details/livingatendofage0000klaa.

Note 3: Cf. Abraham Hartwich, Geographisch-Historische

Landes-Beschribung [sic] derer dreyen im Pohlnischen Preußen liegenden Werdern

(Königsberg, 1723), 279, http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/resolve/display/bsb10000874.html.

Note 4: Cf. Ludwig von Baczko, ed., Nankes

Wanderungen durch Preussen, vol. 2 (Hamburg and Altona, Vollmer, 1800),

111-125, https://archive.org/details/reisedurcheinen00baczgoog/page/n378/mode/2up; OR https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:70-dtl-0000000449#061, 112f.

Note 5: Benjamin H.

Unruh, “Die Wehrlosigkeit.” Vortrag, gehalten auf der Allgemeinen

Mennonitischen Konferenz am 7. Juni 1917, 16, 17, https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/books/1917,%20Unruh,%20Wehrlosigkeit/.

Note 6: In Peter Hildebrand, From Danzig to Russia (Winnipeg, MB: CMBC, 2000), 40. Also in

Gerhard Wiebe, “Verzeichniß der gehaltenen Predigten samt andern vorgefallenen

Merkwürdigkeiten in der Gemeine Gottes in Elbing und Ellerwald von Anno 1778 d.

1. Januar.” Transcriptions from the original by Willi Risto, https://chortitza.org/Buch/Risto1.pdf;

also Ingrid Lamp: https://mla.bethelks.edu/Prussian%20Polish%20Mennonite%20sources/wiebe.html.

Note 7: B. H. Unruh, “Geleitwort,” in Das Mennonitentum in Rußland von seiner Einwanderung bis zur Gegenwart, by Adolf Ehrt, III–VI (Berlin-Leipzig: Belz, 1932), IV, https://chort.square7.ch/Pis/Ehrt; also B. H. Unruh, “Das Wesen des evangelischen Täufertums und Mennonitentums,” Mennonitische Jugendwarte 17, no. 1 (February 1937), 12f., https://mla.bethelks.edu/gmsources/newspapers/Mennonitische%20Jugendwarte/DSCF9305.JPG.

Note 8: Zacharia Theobaldo, Der alten und neuen Schwärmer

widertäufferischer Geist (Cöthen: Meyer, 1701), front pages, https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb11204036_00005.html.

Compare the etchings in Thieleman van Braght, The Martyrs’ Mirror: The Story of

Fifteen Centuries of Martyrdom (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 2001), https://archive.org/details/MartyrsMirror.

Also Rachel Epp Buller, "Beyond the Martyrs Mirror: The Prints of Jan

Luyken," Anabaptist Historians (Jan. 2018), https://anabaptisthistorians.org/2018/01/25/beyond-the-martyrs-mirror-the-prints-of-jan-luyken/.

Comments

Post a Comment