Simple proximity to a place of horrors does not equal knowledge or complicity. Many Gnadenfeld-area Mennonite refugees were, for example, temporarily housed 20 km. away from the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp where 15-year-old Anne Frank died ultimately of typhus (note 1). The day after liberation by British troops on April 15, 1945, camp survivors began to flow through neighbouring villages. “What a sight they were! They had been tortured and starved, and were swollen from lack of food. … We could hardly believe that the glorious country of Germany could commit such crimes against people,” Susanna Toews wrote (note 2). My mother was only seven, but she remembers overhearing shocking descriptions given by their host family’s teenaged girls forced by the British to clean some of the camp buses.

What about the much larger death camp at Auschwitz?

There is a book entitled: A Small Town near Auschwitz:

Ordinary Nazis and the Holocaust. It is about an administrator living near the

concentration camp who claimed after the war to have known nothing related to

the camp’s activities, nor did he recognize his roles as complicity in the

system or need for contrition (note 3).

Curiously only 20 km from Auschwitz in Upper Silesia (today Poland), 301 Mennonites from Schönhorst (Chortitza) spent 14 months in a very different kind of camp. They had been evacuated from Ukraine in October 1943 and placed in the resettler camp (Umsiedlerlager) in Zator—on a rail line and one of the few roads that lead directly to the death camp. It was a small town of ca. 2,000 with space: until recently 22% had been Jewish (note 4).

424 other Mennonites from Schönhorst and Rosenbach were 40

km away from Auschwitz in the town of Bielitz where until summer 1944 laundry

from Auschwitz was delivered (note 5). Between May and July 1944, some 438,000

Hungarian Jews were brought to Auschwitz, for example; did any Mennonites from

these two villages notice or hear anything different?

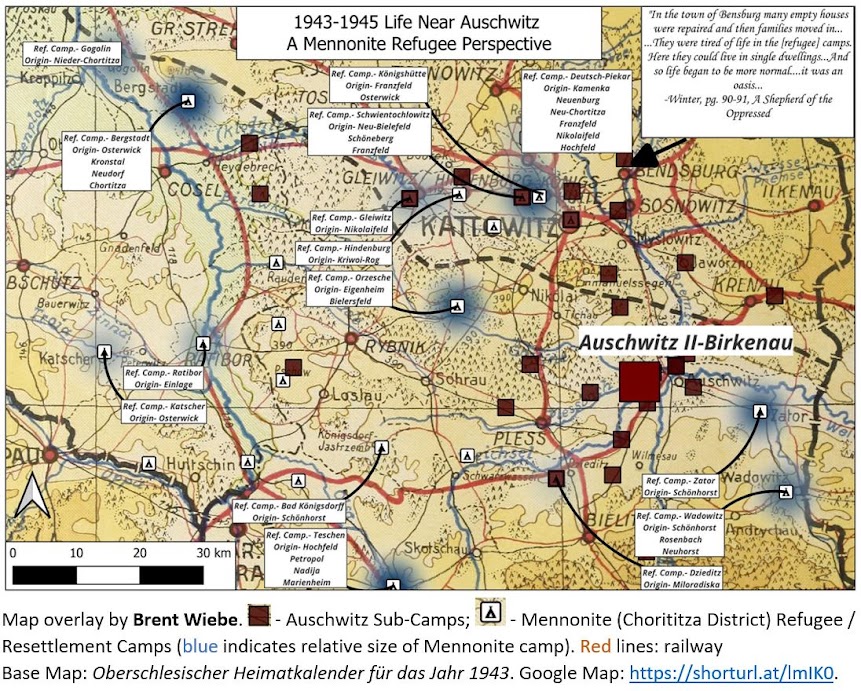

Thousands of Auschwitz inmates were used for slave labour on area livestock farms, ammunition factories, and mines. While the Schönhorst camps were closest to Auschwitz, 6,700 other Chortitza-area Mennonites were distributed in 47 other resettler camp locations in Upper Silesia. (The map above as well as an interactive Google map [https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1arzkKb8kOACYDcQ6P3ze1cP9SuAOAUw&hl=en&ll=50.17047662482064%2C18.733070500267285&z=10] show their proximity to the 40-plus Auschwitz subcamps; note 6). After a mandatory 5-week quarantine period, Mennonites also worked locally for more than a year on farms, mines, factories and with the railway. What did they hear or witness?

At least one Mennonite resettler family in Upper Silesia

with two mentally handicapped children was a victim of Nazi racial health

policy. “They took the children from them and the parents were told later that

the children had died” (note 7). But as a rule Mennonites in Upper Silesia knew

that they were beneficiaries of the policies of race, both materially and

socially.

Not long after their arrival, authorities approved a visit from Prof. Benjamin Unruh as advocate to encourage and to guide his co-religionists in successful resettlement. Unruh travelled with papers confirming he is “charged with the care of the ethnic Germans from Russia by order of the Reichsführer-SS [Himmler] … All offices of the [Nazi] Party, the State and the Military (Wehrmacht) are requested to allow Prof. Dr. Unruh to travel unhindered and to provide him with protection and assistance if necessary” (note 8). Unruh had met with Himmler personally over New Years after Himmler’s “positive” visit to Halbstadt (Molotschna) exactly one year earlier. Unruh—born in the Soviet Union—was highly respected in German government circles for his relief work for Germans abroad and refered to by Himmler as the “Mennonite Pope” (note 9).

Himmler had complete say over who was considered German,

where ethnic Germans should live, and which people groups should be moved from

their homes or destroyed to make room for ethnic German resettlers. Himmler

also designated Auschwitz for the place of an extermination camp.

Unruh’s task was in alignment with Himmler’s larger goals in his role as “Reich Commissar for the Strengthening of the German Ethnic Stock (Volkstum).”

In the administrative centre of Kattowitz Unruh met with

SS-Obersturmführer und Director for Operations in Upper Silesia Lechner. They

agreed that in each district of the Gau two Mennonite worship services would be

held per month. On other Sundays they were free to visit a local Protestant

worship service. Resettler Camp Leaders were instructed to assist the seven

approved Mennonite preachers to find suitable spaces outside the camp,

including nearby Protestant churches, for worship space (note 10).

Unruh reported to the denominational executive that on one Sunday per month a “celebration service” takes place in the camps “which our people enjoy attending” (note 11). The purposes of the Nazi Party Sunday “Morning Celebration” (Morgenfeier) was “to awaken and kindle forever anew the forces of instinct, of emotion and of the soul which are vital for the struggle for existence and the bearing of our people and our race for all times” (note 12).

Between December 13 and 18, 1943, Unruh travelled by train through Upper Silesia to meet and speak to his 7,000 brethren with meetings at eleven different camps. “We were overjoyed to have Benjamin Unruh in our midst. He was like a father to us,” Henry Winter recalled (note 13). Unruh met initially with officials and discussed the future ordination of ministers, confirmed their freedom not to swear an oath, the freedom to visit family members in other camps, the freedom of youth to attend worship services, and the larger problem of Mennonites denunciating others in the camps as former communists, etc., and confirmed that correspondence with family overseas would be regulated by the German Red Cross. Unruh solidified connections with District Camp Leaders Untersturmführer Effer (Bielitz) and SA-Sturmbannführer Zeisberg, who apparently listened eagerly to two of Unruh’s lectures (note 14). In the gatherings Unruh focused his talk on unity within the (Mennonite) community, spent a day with Aeltester-elect Heinrich Winter Sr., and held a workshop for their approved preachers.

Notably boys between 12 and 15 were not in attendance but

were in Hitler Youth Camp. Their training was physically rigorous, the barracks

drafty with little heat and, unlike the resettler camp, the food was sparse and

poor quality (note 15). Multiple accounts indicate that parents were not happy

(note 16). The camp goals were to “harden” the boys and to “indoctrinate them

in the tenets of National Socialism” (note 17).

In Upper Silesia at least two Mennonite resettler camps (Bergstadt

and Annaberg) were former monasteries, one was a former teachers’ residence,

one had been a home for the mentally ill, etc.Victor Janzen from Osterwick who

was in the Hitler Youth noticed that Bergstadt had been cleansed of Poles who

“had had to leave their homes and live in camps as we did” (note 18). All of

annexed Upper Silesia was to be fully “Germanicized” which meant the removal of

Poles and Jews and resettlement with primarily ethnic Germans from the east.

This was not a secret but a plan for which Auschwitz and resettlers like the

Mennonites were connected.

“We also had conversations about politics and noticed that

there was much hostility to Hitler. In Russia the so-called Hitler greeting had

been inculcated in us, but when we greeted people with ‘Heil Hitler’ here we

were met with silence. If we greeted people in the local customary way by

saying Grüß Gott, people were friendly and eager to talk.” (Note 19)

What were those conversations? The transformation of the

town Bendsburg brings much of the larger undertaking into focus and connects

Mennonites to Auschwitz in an important way.

Bendsburg (Bendzin) outside of Kattowitz had a predominantly

Jewish population of 18,670 in the Jewish Quarter as late as April 1943—more

than 50% of the town’s total population. With racial cleansing—ghettoization

and then deportation in August—the town was prepared for full Germanization one

year later; no Jews remained (note 20).

In May 1944, the 96 Einlage Mennonites in the Klein

Gorschütz Camp was resettled in Bendsburg (note 21)—and many more soon

followed. A month earlier the Upper Sileisian newspaper ran a story on “How

Bendzin Became Bendsburg: A Picture Archive Tells the Transformation of the

Town.” It captures the dehumanizing, violent tone and plans of the times in which

Jews and Mennonites were enmeshed.

“April 4, 1944 - More than 25,000 Jews, including the most depraved offspring of this race, populated today's Bendsburg and formed the majority of the inhabitants. The so-called city administration was housed in a few dilapidated rooms, and the entire cityscape reflected the same. ... [Now after] three years of successful German reconstruction work ... it is impossible to list everything that the German administrative spirit has thought up to create a German Bendsburg out of an almost completely Judaized Bendzin.”

Bendsburg was now free of Jews, and with housing and

infrastrucure completely rebuilt, it was ready for ethnic Germans like the

Mennonite evacuees from the Chortitza District. Henry Winter recalled:

“More and more of our people moved to Ben[d]sburg. They were

tired of life in the camps. Here they could live in single family dwellings, do

their own cooking and they received food vouchers. And so life began to be more

normal. A large hall that could seat 400 was secured for our worship, but it

was soon too small. … For refugees in Ben[d]sburg it was an oasis, the quiet

before the storm.” (Note 23)

Two months before Mennonites arrived in Upper Silesia, Bendsburg’s Jews were brutally removed from the town and taken 48 km by train Auschwitz. Mennonites would have known about the town’s “transformation” for Germanization; the papers made no attempt to hide the town’s Jewish past.

As noted above, I do not think proximity to a place of

horrors equals knowledge or complicity.

But perhaps there is space and need for another book: “A

Small Town near Auschwitz: Ordinary Mennonites and the Holocaust.” And of

course, I always wonder how this era of Mennonite experience impacted or had to

be unlearned in the Mennonite congregations with which I am connected (note 24).

---Addendum, November 4, 2023---

The Bata Shoe and Leather Factory in Chelmek (Poland) Upper

Silesia, was 8 km from Auschwitz. A number of Mennonites worked here in 1944.

Heinrich Johann Fast, b. 1909 (GRanDMA #203662), was evacuated with others from Osterwick (Chortitza) to Upper Silesia in October 1943. Fast together with 340 other Mennonites from the villages of Osterwick, Kronstal, Neudorf, and Chortitza was brought to the Bergstadt Resettler Camp.

After quarantine adult resettlers were placed in various

types of employment. At least four Mennonite men aged 27 to 35 were deployed to

work in the Bata factory.

These men were not in Bergstadt when they and their families

were officially naturalized as German citizens six months later, but at work in

Chelmek--so close to the massive Auschwitz concentration camp.

Fast’s family's EWZ form notes that he was in “Chelmek bei Auschwitz,” working at the Bata Shoe and Leather Factory. He was here together with Peter Jak. Klassen, b. 1908 (#995187), Peter Jac. Friesen, b. 1910 (#910121), and David “Peter” Dyck, b. 1916, (#586542) and no doubt others (see their EWZ forms linked with their GRanDMA profile). With naturalization, Dyck had his Jewish-sounding name "David" changed officially to Peter.

In 1944 Bata’s Chelmek factory had 2,783 employees and manufactured 2,557,300 shoes. With German occupation in 1939, it had come under German administrative oversight and for a brief time in 1941 used Auschwitz inmates outside the factory to clean the ponds for the factory’s water needs (note 25).

The Janinagrube sub-camp of Auschwitz was however active at

this time (1944); it was only 4 km from the Bata factory in Chelmek and had

some 600+ Auschwitz inmates working in its coal mine.

What did they hear and see and know about Auschwitz and the sub-camp Janinagrube?

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

For the interactive Google Map, https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1arzkKb8kOACYDcQ6P3ze1cP9SuAOAUw&hl=en&ll=50.171511232527955%2C18.733070500267285&z=10.

Note 1: Anne Frank was taken from her attic hideout in

Amsterdam by the Nazis in August 1944, and became known around the world when

her diaries were published after the war.

Note 2: Susanna Toews, Trek to Freedom: The Escape of Two

Sisters from South Russia during World War II, translated by Helen Megli (Winkler,

MB: Heritage Valley, 1976), 36.

Note 3: Mary Fulbrook, "A Small Town near Auschwitz":

Ordinary Nazis and the Holocaust (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Note 4: Sybille Steinbacher, “Musterstadt” Auschwitz.

Germanisierungspolitik und Judenmord in Ostoberschlesien (München: Saur, 2000),

41.

Note 5: Steinbacher, “Musterstadt” Auschwitz, 199.

Note 6: The Auschwitz sub-camps are well documented and

research. E.g., see https://www.auschwitz.org/en/history/auschwitz-sub-camps. The Wikipedia list is helpful: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_subcamps_of_Auschwitz.

I have created an Excel list of the Mennonite resettler camps in Upper Silesia (pic

below) from: Benjamin H. Unruh, “Vollbericht,” to Executive of the “Vereinigung

der deutschen Mennonitengemeinden,” January 7, 1944, Appendix 1. Benjamin H.

Unruh Collection, Abraham Braun Correspondence, 1930, 1940, 1944-45,

Mennonitische Forschungsstelle Weierhof.

Note 8: Certificate from SS-Obersturmführer und

Einsatzführer Oberschlesisen Lechner on behalf of the Gau President and the Office

of the Reichführer, December 13, 1943, copied in Unruh, “Vollbericht,” Appendix

3; also similar: Lechner to District Camp Leaders in Oderberg, Bergstadt,

Hindenburg, Königshütte, Ratibor and Bielitz, December 13, 1943, copied in

Unruh, “Vollbericht,” Appendix 2.

Note 9: On Unruh, see my essay: “Benjamin Unruh, MCC

[Mennonite Central Committee] and National Socialism," Mennonite Quarterly

Review 96, no. 2 (April 2022), 157–205, https://digitalcollections.tyndale.ca/handle/20.500.12730/1571.

Note 10: Lechner, Aktenvermerk über die Besprechung mit

Hernn Prof. Benjamin Unruh, December 22, 1943, in Unruh, “Vollbericht,” Appendix

4.

Note 11: Unruh, “Vollbericht,” 5.

Note 12: Cited in Aryeh L. Unger, The Totalitarian Party:

Party and People in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1974), 174. Cf. also Helene Dueck, Durch Trübsal und Not (Winnipeg, MB: Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 1995), 49, https://archive.org/details/durch-truebsal-und-not/mode/2up.

Note 13: Henry H. Winter, Shepherd of the Oppressed. Heinrich

Winter: The Last Aeltester of Chortitza (Leamington, ON: Self-published, 1990),

87.

Note 14: Unruh, “Vollbericht,” 4b.

Note 15: Maria (Klassen) Harder, “Tagebuch, 1907-1965 (part

9),” Mennonitische Rundschau 89, no. 34 (August 24, 1966), 14, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1966-08-24_89_34/page/14/.

Note 16: See also the memories of Victor Janzen, From the

Dniepr to the Paraguay River (Winnipeg, MB: Self-published, 1995).

Note 17: Abram Janzen for Gerhard Fast, Das Ende von

Chortitza.

Note 18: V. Janzen, From the Dniepr, 55.

Note 19: Abram Janzen for Gerhard Fast, Das Ende von

Chortitza.

Note 20: Steinbacher, “Musterstadt” Auschwitz, 292; 301.

Note 21: “Helene Pauls,” (obituary), Mennonitische Rundschau

95, no. 46 (November 15, 1972), 12, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1972-11-15_95_46/page/12/.

Note 22: “Wie aus Bendzin Bendsburg wurde: Ein Bildarchiv erzählt

die Wandlung der Stadt,” Oberschlesische Kurier 76, no. 94 (April 4, 1944), 3, https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/130982/edition/123058/content.

Note 23: Winter, A Shepherd of the Oppressed, 91.

Note 24: In January 1945 as Soviet forces penetrated the Upper Silesia and the flight of Germans westward began, older men were conscripted into the Volkssturm. See the war diary of one Mennonite who had resided in Bendsburg: “The War Diary of Jakob Günther: Bendsburg, Upper Silesia, Germany,” with an introduction by James Urry, translated by Jack Thiessen, Mennonite Quarterly Review 92 no. 2 (April 2018), 207-224.

Note 25: (Addendum): On the Bata factory, see https://world.tomasbata.org/europe/poland/. See also Geoffrey Megargee, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Volume I (BIoomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009), 221 (map); 236f. (Chelmek); 253-255 (Janinagrube), https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/3/oa_monograph/chapter/3209396.

Comments

Post a Comment