The biggest temptation of genealogical or in-group history writing is “hagiography”– literally “writing about the lives of saints,” i.e., idealizing a subject matter, writing about a person or people in an unreal, flattering light. Hence the title of James Urry’s classic: “None but Saints” (quote from an Alexander Pope poem: “Vain Wits and Critics were no more allow'd, When none but Saints had license to be proud;” note 1).

Group histories like the Russian Mennonite story are cluttered with myths in need of deconstruction—whitewashed or highly selective accounts, e.g., of the “Golden Years,” of a persecution narrative—either by outsiders, or from the enemy group within because of division—of stories of amazing self-accomplishment, wealth or group accomplishment without recognition of privilege and context—or perhaps exploitation.

Family storytelling inevitably leaves much unsaid, and most

of that is up to the family to decide to record or not. For example, a birth

out of wedlock is not especially important for the outside historian, but for a

family member it may be an interesting and important trail to follow up—maybe

because of a roadblock in the genealogy, and DNA results arrive. If it involves

a minister, teacher or other community leader, then it becomes a group story.

Next generation genealogists wanting to be proud of their

family story often leave what has been passed on unexamined. Upon closer

examination, however, it may become clear that someone is missing; the dates

don’t add up; it is simply not plausible; a whole number of years are missing

from the story; etc. Some writers are conveniently “silent” about an era or

critical years in their family or personal story, e.g., of their grandfather’s

activity in the Stalin years, or their role in the messiness of German occupation.

I know such cases. Sometimes blatantly false information is passed on to save

face; the truth can be painful.

Of course, one might say: “Stay out of other people’s

genealogy; that’s their family’s story to tell or not, not yours!” But others

will counter that that individual’s story is not simply private—the actions

impacted many people significantly, and his/her name must be recorded and the

story be told truthfully, fully and accurately.

Why? It can be important not only for the healing of family

memory, but these larger stories can offer insights and healing for the larger

Mennonite family (e.g., for an understanding of congregational dynamics in the

past and present) and credibility for Mennonite history writing generally.

A review of the loosely edited materials in two volumes on the village of Einlage by Heinrich Bergen have given me occasion for this reflection (note 2). To be fully transparent, I have long had an interest in the village of Einlage on the Dnieper River because for some eighteen years one of my more illustrious ancestors lived and taught there pre-1828 (NB: notice the temptation of hagiography!).

But more importantly, Bergen’s collection gives a very fulsome and detailed picture of what happened with Mennonites upon arrival of the German military in August 1941—which is of great interest to me. Some of his materials collected are raw and clearly un-varnished. I have taken a handful of individuals mentioned multiple times by multiple contributors in the Bergen collection, and compared that information with their respective “Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry” (GRanDMA, https://www.grandmaonline.org) entries. The latter are based on existing Mennonite genealogical collections and more recent family submissions, and reviewed by volunteer editors. Some of the entries are also complemented by the individual’s application for German naturalization in 1944 (EWZ form; note 3), where in one case the falsification of the family record is already obvious. I have chosen not to give the name of the individuals, but to identify the as “Mennonite A, B, C, D, E, F, G and H.”.

---

Mennonite A (I, 336) “... was shot as a communist by the German Wehrmacht in the first days of occupation in August 1941. He had first to dig his own grave.” (I, 364): “Chief Officer Hess shot ‘Mennonite A,’ but he left the others (“Mennonite B” and Mennonite C”) free for the time being until the local civil administration (with ‘Mennonite Mayor E’ and assistant ‘Mennonite F’) could take on their duties.”

- Mennonite A’s story submitted to GRanDMA is falsified: “Died August 22, 1941 … Heinrich was forcibly taken away by the Russians in 1941.”

Mennonite B (I, 333): “... was arrested by the German police

of the left (east) bank as a communist. He strangled himself in jail. His son

lives in Winnipeg.” (I, 202): “Before 1941, ‘Mennonite B’ was the chair of the

village council for multiple years, and was shot during the period of German

occupation. (I, 367): “‘Mennonite B’ was arrested in Einlage by police from the

left bank; a very tough interrogation followed. ‘Mennonite B’ hung himself in

his cell.”

- Mennonite B is not in GRanDMA, but his father Peter is. His parents and siblings are listed in Bergen (I, 202) as well as his children (I, 337); none are in GRanDMA.

Mennonite C (I, 527; 234): “... was a chairperson of the

Einlage Kolchos (collective farm) and executed by the Mennonite [!] police [15 young Mennonite men appointed by mayor 'Mennonite E', II, 117]. His

widow [with name] lives in Winnipeg with her sons, First Mennonite Church.

- Mennonite C in GRanDMA; a false story was submitted: “He was shot to death before WWII.” NB: WW II began in 1939; came to the USSR in 1941. This also conflicts with the EWZ form (written in 1944), which states something equally implausible: “husband was arrested by the Soviets in 1942.” NB: arrests by Soviets happened before August 1941. In both cases—in 1944 and in later genealogical materials—the family attempts to hide a story.

Mennonite D (I, 364): “... was handed over to the police, alleged to have cut the telephone wires of the field telephones." (II, 75): 'Mennonite D' is from Neuendorf. Upon the initiative of mayor 'Mennonite E,' resident 'Mennonite D' was shot by the German Wehrmacht. (II,117): "Mayor 'Mennonite E’s' first horrible task was to have 'Mennonite A' and 'Mennonite D' as former informers shot.” (I, 365): "... shot by the Hungarian troops [allies to Germany]."

- Mennonite D in GRanDMA: using the EWZ forms, GRanDMA accurately adds the note: “In 1941 he was shot by ‘S.D.’ [Sicherheitsdienst].” However, GRanDMA does not confirm this in the “date of death” for him.

Mennonite E, mayor of Einlage. Bergen gives multiple stories

of his appointment/election as mayor of Einlage and then mayor Saporoshje under German occupation (II, 75; 79; 117; 107); but regarding the

execution, Bergen notes that now in Canada "Mennonite E" denies any

role in the executions.

- Mennonite E in GRanDMA. “'Mennonite E' was a teacher … . He was a bookkeeper of Dneprostroj [hydro dam] from 1930 to 1941.” That he was appointed mayor when the Germans arrived in Einlage, and then after a few months, mayor of the city of Saporoshje, however, is not deemed worthy of mention. Similar silence on his roles between August 1941 and evacuation in 1943. Both the archival summary of files he deposited in the archives in Winnipeg, as well as in his obituary in Der Bote, are silent about this two year period (note 4).

Eight Mennonites in total were executed in Einlage during

German occupation; Bergen adds names of other informers /Mennonite communists:

“Who were they? Our Mennonites, our brothers in faith ... Braun, Winter, Wiens,

Heide, Kehler, Janzen, and others. And after their measure was full [as

informers], they too were arrested and banished. Teacher Janzen ended his life

with suicide” (II, 76f.).

Bergen also names the Mennonite "Police Chief" in Einlage and the Mennonite Gestapo representative and their attempts to change their identity. Mennonite G (II, 118): "... took over the functions of the secret state police (Gestapo) in Einlage. He especially excelled in chicanery against Ukrainians and Russians. Binge drinking was often organized [with/for German officers], especially when 'Mennonite H' took over the role of police chief. Ukrainian girls and young Russian women had to serve him and his assistants. In their police uniforms they were later resettled in the German Reich. After naturalization, when they were told: "Now prove your promise given to the Führer," they suddenly identified as non-resistant Mennonites again and wished to enjoy the heritage of our fathers together with the faithful Mennonites. However, they were taken for ditch digging (Schipparbeit). ... This is a small chapter on the misuse of the Mennonite Confession of Faith.”

The four who were executed, plus the example of the mayor and others,

suffice to make the point about whitewashing and hagiography, selectivity of

memoirs, missing information, falsification of family stories, silence and ...

the need to dig deeper.

Why tell accurate family stories from difficult times? They

are certainly more interesting and relatable than hagiographical accounts. When

one wipes away the whitewash from family and community narratives, it is

possible to “heal memories,” for example, even if difficult and not without

risk. And we can do no better for next generations than to pass on honest

family stories, accompanied with our own “tentative learnings” that may be of

value in new, challenging or toxic contexts.

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: James Urry, "None but Saints." The Transformation of Mennonite Life in Russia, 1789-1889 (Winnipeg, MB: Hyperion Press, 1989). The full quote from Pope is give in the front material.

Note 2: Heinrich Bergen, ed., Einlage/ Kitschkas, 1789–1943:

Ein Denkmal [vol. I] (Regina, SK: Self-published, 2008); idem, Einlage: Chronik des

Dorfes Kitschkas, 1789–1943 [vol. II] (Saskatoon, SK: Self-published, 2010). Copies at the Mennonite Heritage Archives, Winnipeg, MB.

Note 3: Cf. “Index of Mennonites Appearing in the

Einwandererzentrallestelle (EWZ) Files,” compiled by Richard D. Thiessen, https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/EWZ_Mennonite_Extractions_Alphabetized.pdf.

Note 4: See recent scholarship on Mennonite E's role in the execution of Jews and others in Einlage: Dmytro Myeshkov, “Mennonites in Ukraine before, during, and immediately after the Second World War,” in European Mennonites and the Holocaust, edited by Mark Jantzen and John D. Thiesen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 208, 210f., 219, 221, 225 n.33; also: Aileen Friesen, “A Portrait of Khortytsya/Zaporizhzhia under Occupation,” in Jantzen and Thiesen, eds., European Mennonites and the Holocaust, 236. On "strategies of identity modification," see Steve Schroeder, "Mennonite-Nazi Collaboration and Coming to Terms with the Past: European Mennonites and the MCC, 1945-1950," Conrad Grebel Review 21, no. 2 (Spring 2002), 6-15.

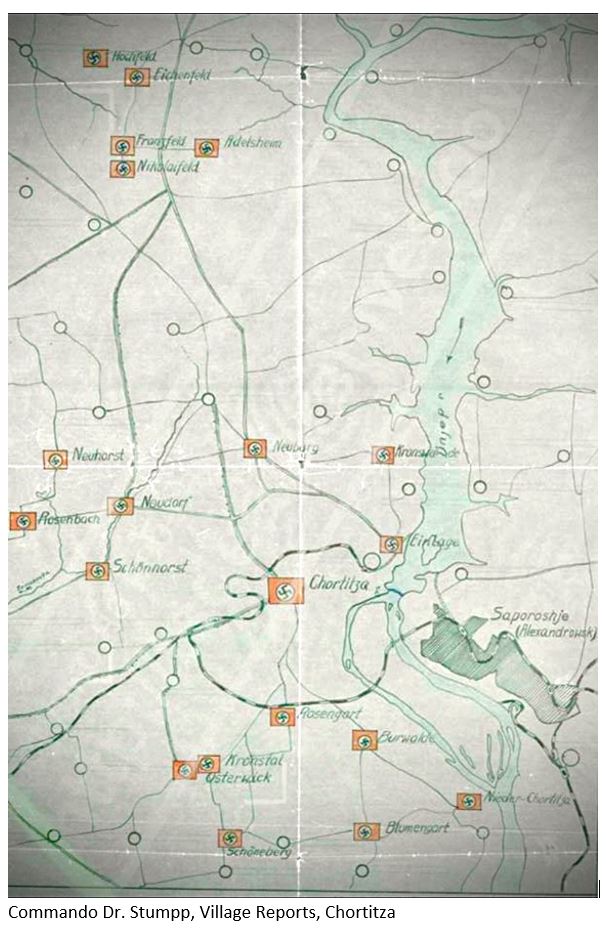

For maps: “Commando Dr. Stumpp” Village Reports, Bundesarchiv, for: Kronsweide, BA R6/622, Mappe 86, May 1942 (TSDEA; Bundesarchiv); Neuenburg, BA R6/622, Mappe 87, May 1942 (TSDEA; Bundesarchiv); Einlage, BA R6/621, Mappe 83, May 1942 (TSDEA; Bundesarchiv).

--

To cite this page: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "Genealogy, or: The Art of Whitewashing and Hagiography," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), August 13, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/08/genealogy-or-art-of-whitewashing-and.html.

Comments

Post a Comment