It is rare that Mennonites make the news for their protests to pressure government or industry. Here is one example.

The agricultural machinery factories in in the Greater Zaporozhzhia-Alexandrovsk

economic zone—including the villages of Chortitza, Einlage, Osterwick, and

Schönwiese—were places of significant labour unrest in the early 1900s (note 1).

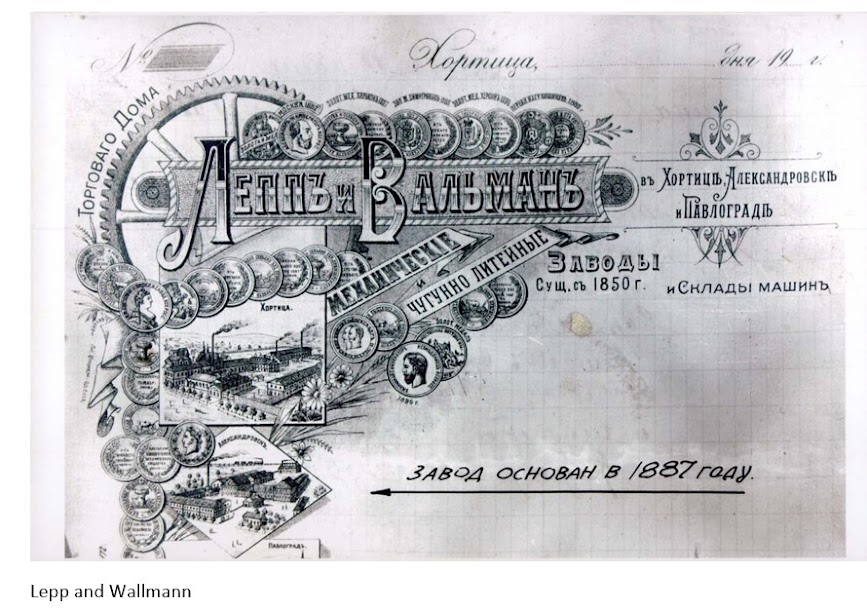

In February and March 1905 factory workers mobilized at the

Mennonite factories of Schulz, and of Lepp and Wallmann in Alexandrovsk, where

the following demands were made:

- an 8-hour workday

- a weekly or bi-weekly pay schedule

- courteous treatment of employees

- immunity from punishment for elected labour representatives

- minimum wages

- no child labour

- appropriate equipment for moving heavy weights

- free family medical care

- free schooling for children

- workmen’s compensation

- regulation of overtime

- factory hygiene including showers and proper air ventilation

- lunch room facilities

- conflict resolution mechanisms

- the abolition of fines

- accidental death benefits. (Note 2)

Most of the demands were not accepted by the industrial

owners.

Elected labour representatives and negotiators at the Schulz

plant in 1905 included Mennonites Peter B. Neufeld, Eduard Sawatzky, Heinrich

Neufeld and Jacob A. Dick (note 3).

A small number of the Mennonite intelligentsia were

sympathetic to these types of liberal reforms, and some were active in early

revolutionary Bolshevik cells, including Cornelius Thiessen of Neuendorf,

Johann Hildebrand of Neuendorf, and Peter Rempel of Nieder-Chortitza, the son

of a prosperous farmer (note 4).

Mennonite factory owners initiated lockouts to break the labour uprisings and strikes of 1905 (note 5), while agitators organized at great personal risk. Cornelius Thiessen, for example, was exiled from Russia and moved with his Jewish wife to Buenos Aires, where he became a leader in the Socialist Party of Argentina. Some years later at their 1912 party congress, he reported that the party had formulated a “resolute protest against Tsarism, against Russian political [interference] in Finland and Persia, and also sent a brotherly greeting to the imprisoned Social Democratic faction of the second Duma, etc.” (note 6)—reflecting perhaps the reasons for his own activism in Russia a decade earlier. Thiessen’s published reports in the German socialist journal Die Neue Zeit reflect a nuanced understanding of Marxist theory, with significant historical knowledge and understanding of the roots of socialism—reaching back to the peasant uprisings of sixteenth-century Europe in which South German Anabaptists had their origins.

Similar labour strikes and bloody clashes were reported in Waldheim,

Molotschna where Mennonite mill owners (J. J. Neufeld) suppressed strikers with

the assistance of police. The workers were barred from returning to their

employment and many resettled in large numbers in the Siberian village of

Miloradovka in the Pavlograd District.

The ministerial had not yet grasped the gravity of the

social issues of their time; few were alarmed by the resentment simmering in

the country as a whole with respect to land ownership, industry, and

labour-relations.

As late as 1903, the older and still influential Molotschna

elder and former missionary Heinrich Dirks regarded the landless poor who

complained as either impatient, lazy, or negligent. He expressed complete

satisfaction with the wise Mennonite land acquisition and distribution

policies, and considered loud disputes at the regional or village levels as an

“evil” and a sign that some Mennonites are “not yet the quiet in the land …

which does not correspond to their calling to be non-resistant” (note 7). Contemporary

historian-minister P. M. Friesen noted that the Mennonite ...

“… social and economic condition was so good (if not

excellent), that they could not expect anything positive for themselves from a

possible, more or less radical, governmental change. To the contrary, as a

genuine Christian-conservative and generally bourgeois group, ninety-nine out

of one hundred Mennonites considered such words as ‘democrat,’ ‘democratic’

with suspicion, foreboding ill, and from a democracy only evil was expected.” (Note

8)

But there were clearly some Mennonite labourers in 1905

whose economic condition was not "so good," and who protested and

pushed for labour rights and work-place health and safety regulations.

During this time, the soon-to-become de facto leader of Russian

Mennonites for the next decades, Benjamin H. Unruh, was studying in Basel,

Switzerland (1900-07). Here the “Religious Socialists” (esp. Leonhard Ragaz)

were making a huge impact on “every thinking Swiss pastor”—even pointing to

early Anabaptists for inspiration—but not on Unruh.

Unruh liked to tell of a meeting in those years in Basel with Lenin, who met with Russian German students. Lenin responded “warmly” to Benjamin Unruh’s speech—according to Unruh, at least!—on the economic contributions of the German colonists to Russian life but also their loyalty to the Russian people (note 9)!

Yet the visions for their respective new world foundations,

and the means to achieve it, were diametrically opposed. Notably Unruh had

received a large bursary for his studies from three wealthy Molotschna

families.

Unruh missed the labour unrest in Russia, and the Christian socialism of Basel never shaped his account of Mennonite faith and life. For Unruh the large gap between rich and poor was not an urgent concern for Mennonite theological debate or activism—despite all the warning signs (note 10).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: Nataliya Ostasheva Venger, “The Mennonite Industrial

Dynasties in Alexandrovsk,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 21 (2003), 89–108;

107, https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/887/886.

Note 2: M. Lvovsky, ed., Na barrikadah, 1905 god v

Aleksandrovske (On the barricades: 1905 in Alexandrovsk) (Zaporozhzhia, 1925),120-122, https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/vpetk400.pdf.

Note 3: Lvovsky, Na barrikadah, 1905 god v Aleksandrovske,

124.

Note 4: David G. Rempel, “Mennonite Revolutionaries in the

Khortitza Settlement under the Tsarist Regime as recollected by Johann G.

Rempel,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 10 (1992), 70–86; 73-74. https://jms.uwinnipeg.ca/index.php/jms/article/view/589/589.

Note 5: Cf. D. Rempel, “Mennonite Revolutionaries in the

Khortitza Settlement.”

Note 6: Cornelio Thiessen, “Der Sozialismus in Argentinien.

Anläßlich des elften Kongresses der P.S.A. am 10., 11. und 12. November 1912,” Die

Neue Zeit. Wochenschrift der Deutschen Sozialdemokratie 30, vol. 1, no. 24

(March 15, 1912), 688–693, http://library.fes.de/cgi-bin/populo/nz.pl; also

idem, “Der zehnte Kongreß der sozialistischen Partei Argentiniens,” Die Neue

Zeit. Wochenschrift der Deutschen Sozialdemokratie 31, vol. 1, no. 19 (February

7, 1913), 856–860, http://library.fes.de/cgi-bin/populo/nz.pl.

Note 7: Heinrich Dirks, “Die Mennoniten in Rußland,” Mennonitisches

Jahrbuch 1903 1 (1904) 5–18; 6f., https://chortitza.org/Buch/MJ/MJ03-18.htm.

Note 8: Peter M. Friesen, The Mennonite Brotherhood in

Russia 1789–1910 (Winnipeg, MB: Christian, 1978), 627, https://archive.org/details/TheMennoniteBrotherhoodInRussia17891910/.

Note 9: Benjamin H. Unruh, “Einige wichtige Erinnerungen aus

meinem Leben und ein Vorschlag,” 2. From Mennonite Library and Archives-Bethel

College, MS. 295, folder 13, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_295/folder_13/.

Note 10: There has been some work on the Kansas Mennonite

socialist J. G. Ewert who argued in 1909 that socialism is in harmony with the

teachings of Jesus. Cf. James C. Juhnke, “J. G. Ewert: A Mennonite Socialist,” Mennonite

Life 23, no. 1 (1968), 12–15, https://mla.bethelks.edu/mennonitelife/pre2000/1968jan.pdf.

A few decades earlier, a Kleine Gemeinde radical and son of a preacher, Abraham

Thiessen (1838-'89) advocated insistently on behalf of the landless in Russia,

and later found his way to Nebraska where he was excommunicated. Cf. Cornelius Krahn,

“Abraham Thiessen: A Mennonite Revolutionary?,” Mennonite Life 24, no. 2 (April

1969) 73–77, https://ml.bethelks.edu/store/ml/files/1969apr.pdf;

and GAMEO: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Thiessen,_Abraham_(1838-1889).

In 1909, the transatlantic Mennonite-based paper Mennonitische

Rundschau republished, for example, an economic prognoses of capitalist,

industrial farming from the Odessa Zeitung that signaled great changes ahead:

Karl Hoffman, “Ein kleiner Beitrag zur Bauernfrage,” Mennonitische Rundschau 32,

no. 32 (August 11, 1909), 15, https://archive.org/details/sim_die-mennonitische-rundschau_1909-08-11_32_32/page/14/mode/2up,

based on an article by Jaroschewitsch in the Odessa Zeitung, no. 128 (1909), https://media.chortitza.org/pdf/lfrs143.pdf.

---

To cite this post: Arnold Neufeldt-Fast, "Mennonite Labour Protests, 1905," History of the Russian Mennonites (blog), June 9, 2023, https://russianmennonites.blogspot.com/2023/06/mennonite-labour-protests-1905.html.

Comments

Post a Comment