By January 2, 1930, over 50 mostly Mennonite children under the age of four had died very suddenly from a measles-like condition in the camps. These children and their families had fled to Moscow in the fall of 1929 and were then rescued to Germany before moving on to Canada, Paraguay or Brazil.

The German government had appointed the Social Democrat

politician Stücklen as Commissioner for German-Russian Aid to oversee all

aspects of the emigration.

The German Communist Party paper Rote Fahne did not waste the opportunity to politicize the epidemic and lampoon Stücklen and all involved. The paper published a grizzly political cartoon depicting the “mass death of the Kulak-children at the Hammerstein camp” with the comment from Stücklen that these deaths are "still better than in the hell of Russia." The paper depicted the Commissar as a smiling “fat-cat” capitalist politician beside the children’s caskets who was happy to use even the worst events to smear the USSR.

Many families like my own had children or grandchildren or nieces and nephews suddenly take sick and perish at one of the camps. My great-uncle Isbrand Janzen (#473153) recorded the following at Prenzlau:

- January 2, Elvera (age 2; daughter) admitted to hospital; Prenzlau

- January 3, Gredel (Margaretha; age 3½; daughter) admitted to hospital; Prenzlau

- January 7, Mika Janzen (relative?) buried.

- January 7, Willy (age 10 months; son) half-day in hospital.

- January 9, Elvera released from hospital

- January 12, Willy admitted to hospital

- January 15, Willy died; 1 AM

- January 17, Willy buried in Prenzlau

- January 24, Gredel released from hospital

The notes reflect how suddenly illness and death came

knocking and hint at just how devastating the epidemic was for the family. Our

family was from Spat, Crimea (note 1; pic 1).

Stücklen “immediately had additional hospital barracks

erected in Hammerstein and called in an additional number of physicians. ...

The camp is strictly guarded. It is forbidden to enter the camp, and the

refugees in the individual barracks are not allowed to visit each other, lest

the disease be spread. Currently, 3200 persons are accommodated in Hammerstein.”

(Note 3).

Some of the children—but not all—were very weak and poorly

nourished when they arrived in Germany, and had particularly low resistance.

The newswire carried the following paragraph, which was reprinted widely:

“The refugees recognize that everything that can be done for

them is being done from the German side. However, it has happened in a number

of cases that mothers have hidden sick children because they did not want to

part with them. The very religious Mennonites, in keeping with the customs of

their former homeland, try to pray the children to health. When searching for

sick children in the camp, many mothers used every imaginable trick to hide

their children from the examining physicians. Exits were guarded and a thorough

search of the barracks was carried out. ... In the Prenzlau refugee camp, a

number of children have also fallen ill with measles. ... The health of

children in the Mölln (Holstein) refugee camp is good.” (Note 4)

The Rote Fahne of sought, of course, to use the epidemic to

reveal a larger scandal, in their eyes:

“In fact, the cause of the rapid spread of the disease after

several weeks of stay in Germany is only to be found in the unsanitary

conditions [of barracks] and the backwardness of the kulaks based on their

religion motives. The bourgeois press itself has to admit that the kulaks

perceived the disease ‘as God’s providence,’ and that at the beginning of the

epidemic the mothers resisted medical treatment. …

The ‘8 O’Clock Evening News’ on January 3 let the cat out of

the bag: its inflammatory article was directed against the Soviet Union with

the headline: ‘The death of children in the refugee camp - still better than in

the hell of Russia.’

Truly, the six million Reichsmarks that were squeezed out of

the German proletarians [for the emigrants] have been well invested for the

bourgeoisie: even the self-incurred mass death of children is brilliantly

exploited for their anti-Soviet agitation [and agenda].” (Note 5)

The Rote Fahne followed the lead of Moscow and viewed

the entire rescue drama of formerly wealthy Soviet German farmers—kulaks—as

deviously orchestrated to embarrass the USSR on the world stage. Not

surprisingly, the Soviet paper PRAVDA headline on January 3 read: “Infection

among Mennonite Emigrants: Capitalist ‘Paradise’ Disappoints.”

Like the Rote Fahne, PRAVDA referred to the German

refugee barracks as “concentration camps” (of course pre-WW2) adding that “many

families are already openly discussing their wishes to return to the USSR”

(January 3, 1930). Two days later the PRAVDA headline read: “Kulak-Mennonites

in their Bourgeois ‘Fatherland’: Anti-Soviet Emigration Campaign fails

Miserably” (note 6).

The “emigration campaign” was led by kulaks and preachers,

according to PRAVDA, and their tricks have ended in catastrophe.

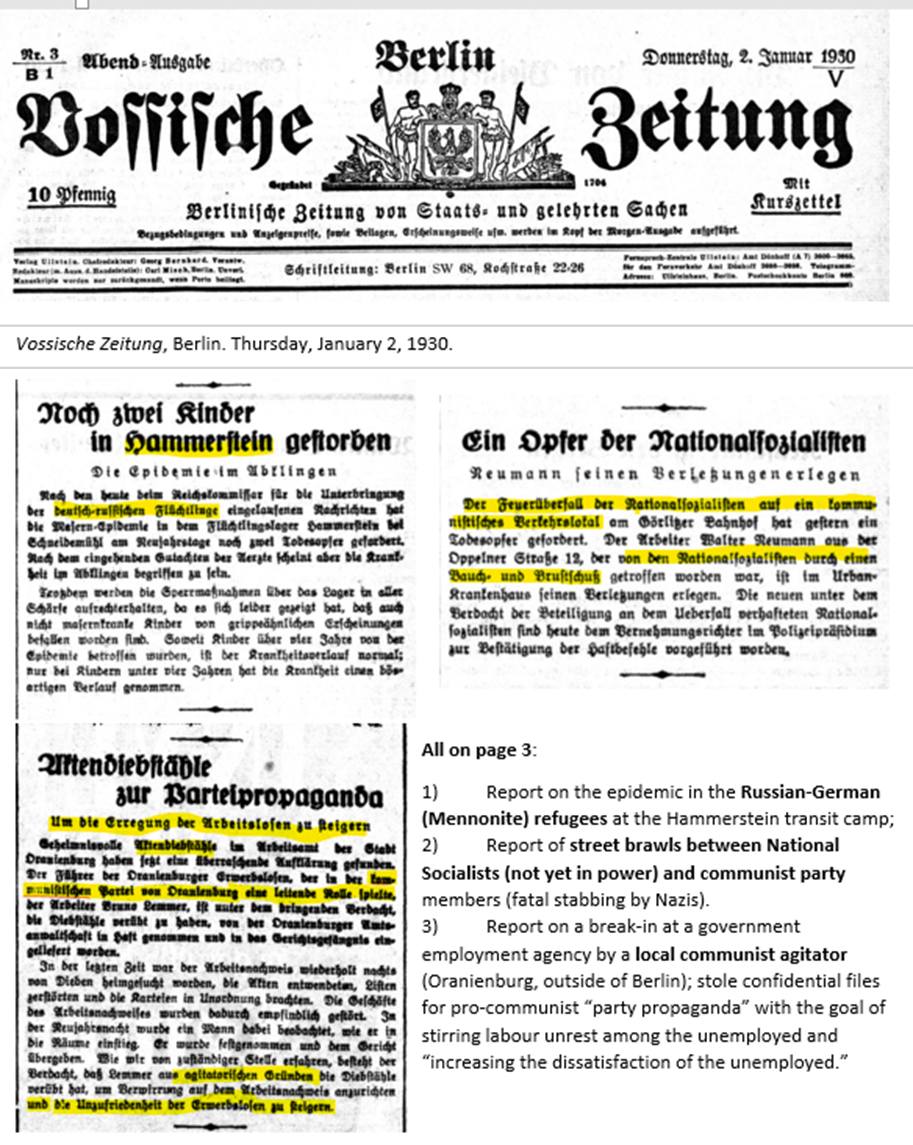

This brutal blame-game also had a context. The Vossische

Zeitung, one of Berlin’s oldest newspapers and sometimes regarded as the

nation’s “newspaper of record,” is telling. It represented the broad liberal

middle-class between the rising parties on the left and the right in 1930—the

Communists and the Nazis.

On January 2, 1930, page 3 (pic) offers a great example of

the political temperature in the country. The VZ page included a

report a) on the epidemic at the Hammerstein camp; b) on street brawls between

the Nazis and communists (Nazis fatally stab someone); and c) on a break-in at

a government employment agency, in which confidential files were stolen by

communist agitators for the purposes of “party propaganda” in order to stir

labour unrest and dissatisfaction among the unemployed (note 7).

In fact, in the VZ from mid-November 1929 to

mid-January 1930, almost every other issue reports on demonstrations, clashes,

shootings, arson, riots, stabbings and street fights between the two radical

parties. The Mennonite refugees would surely have had access to some

newspapers, and would have known this, if not seen it first-hand. In one of the

items, Hitler argued that his paramilitary thugs were necessary because—in his

view—police and state were failing to protect the German people from “organized

Marxist terror.” The flight of "German farmers" in Russia to Moscow

and Germany, their strong anti-Soviet testimony, played perfectly into his

hand.

“In Russia we were treated as enemies, here as friends, even

more, as brothers. After all, German blood also flows in our veins. ... With

all our hearts we implore the blessings of the Most High upon Germany and her

people. May peace and prosperity be granted to the German Fatherland” (Note 8).

---Arnold Neufeldt-Fast

---Notes---

Note 1: I thank John Janzen (Niagara) for the notes

from his father Isbrand (my grandmother’s brother).

Note 2: “Die Epidemie im Hammersteiner Flüchtlingslager,” Deutsche

Allgemeine Zeitung, Morning Berlin edition, January 3, 1930, no. 3

Beiblatt, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/.../PLEKFIHZB....

Note 3: “Masernepidemie bei den Wolgadeutschen,” Volksfreund (Karlsruhe)

50, no. 2 (January 3, 1930), 1, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/.../webcache/1504/3684465.

Note 4: Ibid, and others: https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/.../newspaper....

Note 5: “Massensterben der Auswandererkinder: Die Früchte

der 'Brüder-in-Not' Aktion," Rote Fahne (Berlin) 13, no. 3,

supplement 1 (January 4, 1930). http://ciml.250x.com/.../1930/die_rote_fahne_1930-04-01.pdf.

Note 6: PRAVDA (official newspaper of the

Communist Party USSR), January 4, p. 1; January 5, p. 1; translations from the

Russian by Brent

Wiebe.

Note 7: Vossische Zeitung (Berlin), Thursday,

January 2, 1930, p. 3, https://dfg-viewer.de/show.... For all issues of the Vossische

Zeitung: https://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/.../zdb/27112366/.

Note 8: Vossische Zeitung, December 7, 1929, evening

edition, p. 1, https://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bmets%5D=https://content.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/zefys/SNP27112366-19291207-1-0-0-0.xml.

Comments

Post a Comment